Once at El Bogoi, and in spite of being unwell, I could not rest, so went out again, starting early as usual. I met Lesiat, one of my guides, at the foot of a kopje where we had parted the day before. The spoor of a single elephant was crossed not far from camp, but it was not fresh. Farther on we saw what did seem to be fresh spoor of two or three others in dewy grass and returned to inspect the latter, only to find that it was rhino spoor. We went on again, striking straight through the dense bush, which stretches for miles and miles along the foot of the mountains and covers all the flat country towards the Seya. After a bit we struck the prior night’s spoor of a few travelling elephants and followed for a long time, but the elephants showed no sign of feeding. Finally, we turned back toward camp. I was so tired it was hard to drag one foot after another.

Once at El Bogoi, and in spite of being unwell, I could not rest, so went out again, starting early as usual. I met Lesiat, one of my guides, at the foot of a kopje where we had parted the day before. The spoor of a single elephant was crossed not far from camp, but it was not fresh. Farther on we saw what did seem to be fresh spoor of two or three others in dewy grass and returned to inspect the latter, only to find that it was rhino spoor. We went on again, striking straight through the dense bush, which stretches for miles and miles along the foot of the mountains and covers all the flat country towards the Seya. After a bit we struck the prior night’s spoor of a few travelling elephants and followed for a long time, but the elephants showed no sign of feeding. Finally, we turned back toward camp. I was so tired it was hard to drag one foot after another.

This sort of thing went on for another three days. I hunted assiduously but the only spoor we could find was that of travelling stragglers, the following of which resulted in nothing but profitless fatigue, for they never fed nor halted. Finally, I was convinced there was no herd nearby. The elephants reported by locals had been scared and left the neighborhood and it would be folly to continue here, tearing ourselves to pieces for nothing.

As promised, news of elephants never came, I sent two men to an Ndorobo camp to make inquiries. I was determined to move camp rather than continue wasting time in this camp. My men reported that most of the community was away, but that two men would come to our camp the following day. As promised, they arrived, and with some giraffe meat, and reported elephants on the Barasolio. I at once instructed my head man to prepare for a lengthy excursion. Alas, many days of weary disappointment are common to an elephant hunter. But soon there would be compensation for this turn of bad luck.

The first day we saw only spoor of rhino and zebra, but the second day we came to the edge of a pretty deep valley through which we could see the river Seya winding with patches of green jungle and thorn trees growing along its banks. It was a long, steep, stony descent to the water, which was about 30 yards across, very rapid and 18 inches deep. I decided to camp and search for elephants. In the afternoon, I walked a long way parallel to the river which was fringed, for the most part, with belts of thick forest or dense jungle, sometimes on one bank, other times on both. Beyond this, the ground was open, with short grass and very dry. It was hard to get around, for though the trees were not close, the dense undergrowth was over one’s head and it was hard to force one’s way, even on the game paths.

Even if I saw a giraffe, and got close, the cover was such that I could not get a shot. Squareface, another guide, saw spoor but only of rhino, lots of them. We badly needed more meat. At night, the mosquitoes swarmed up from the swamps lower down the river and disturbed my sleep. The following morning, shortly after leaving, I managed to bag a zebra, oryx and gazelle and returned via the river. Its presence was a blessing, since we could halt whenever we wanted to. But most important, during the day’s march we saw pretty recent elephant droppings on the game path.

So far, there was little change in the character or direction of the valley but we were nearing the spot where the river ended, close to the Matthews Range. The following morning we continued along the river, stopped for a short rest after three hours, and proceeded again, arriving at a valley where the bottom was a wide damp flat covered with tall, dense reedy swamp grass. Here and there were patches of jungle, thorn trees and an occasional stagnant pool. This was a likely place to find the game I desired. Then, on topping a little rise which gave a good view, a great black ear caught my eye. It was waving gently with a sinuous motion reminding me of a fish sleeping in water. Immediately I halted the party; the wind was right.

Leaving the other men with orders to remain absolutely still, I took three gun bearers and two scouts, crossed the river, struggled through the dense jungle and reached a steep, bare, stony hill on the other side. This was close to where the elephant or elephants had been. I say elephants because, even though only one had been visible, I felt sure there were more. Making our way through this formidable cover was difficult. The height of the grass may be inferred from the fact that even from the hilltop vantage point, all we could see was an elephant’s ear. In fact, it was so dense as to be impassable except along rhino and elephant paths, and even then only with difficulty. However, the ground surface was partly dry. In places where there were pools of water, we noted elephant tracks.

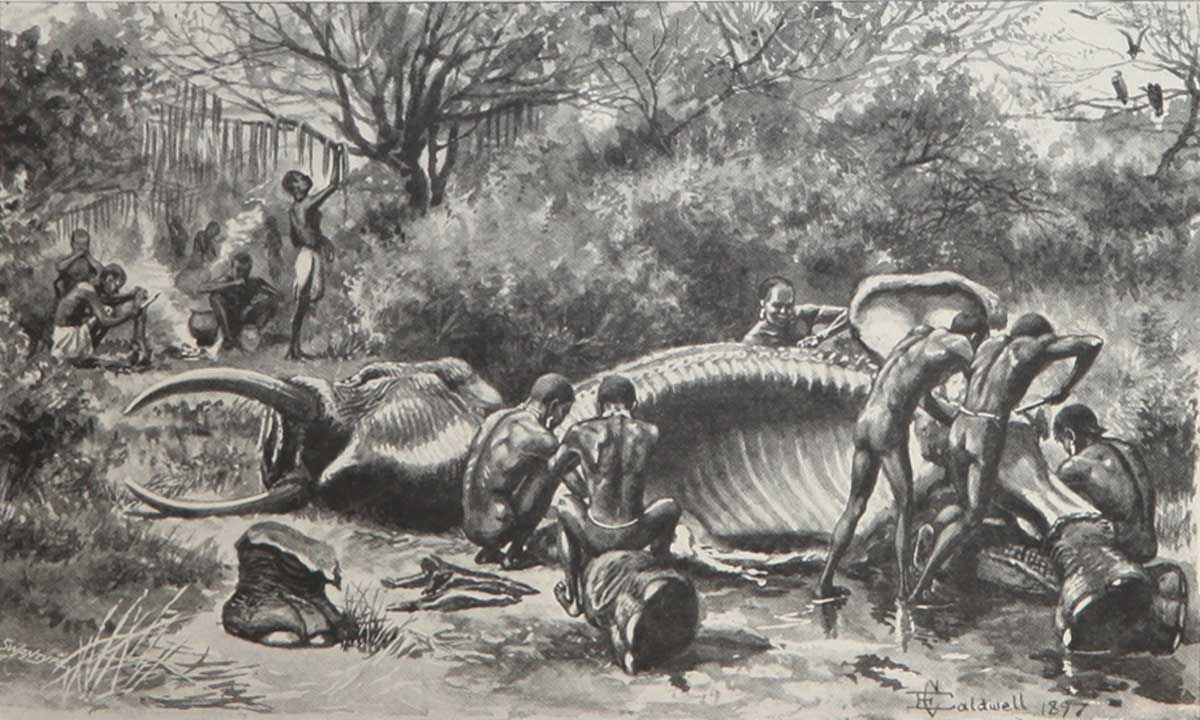

On climbing another hill, we saw that the elephants, yes plural, had moved a little lower down where the grass was not so thick. However, they were on the other side of the river (the side we had come from) and we had to recross. The wind was mostly in our faces, but on reaching a spot where the grass was not so thick, I saw two or three elephants through openings. Alas, a treacherous eddy of air gave them our scent before I could get a shot. As they ran diagonally across, I managed a shot and soon heard the grumblings a dying elephant makes. Approaching cautiously, I could not find the animal, but soon noticed it lying dead among some bushes. Then, in the excitement of my first elephant in several weeks, I foolishly talked exultingly to my men who had arrived, and alarmed the other elephants which had been standing close by, but hidden from us. Thus, I lost a splendid second chance.

On climbing another hill, we saw that the elephants, yes plural, had moved a little lower down where the grass was not so thick. However, they were on the other side of the river (the side we had come from) and we had to recross. The wind was mostly in our faces, but on reaching a spot where the grass was not so thick, I saw two or three elephants through openings. Alas, a treacherous eddy of air gave them our scent before I could get a shot. As they ran diagonally across, I managed a shot and soon heard the grumblings a dying elephant makes. Approaching cautiously, I could not find the animal, but soon noticed it lying dead among some bushes. Then, in the excitement of my first elephant in several weeks, I foolishly talked exultingly to my men who had arrived, and alarmed the other elephants which had been standing close by, but hidden from us. Thus, I lost a splendid second chance.

Following in their wake, we got close to them but in dense jungle. One faced me and as I tried to get into position for a shot, it approached. I waited for it to halt or give me a chance at its chest but, instead of stopping, it came on faster, while its chest remained covered by the tall reedy grass. When it was within five paces, I had to fire over its head and then try to get out of the way. Luckily, the shot turned the elephant. We did not follow at once as it was unpleasantly risky work in this tangle of tall swamp grass. Impenetrable when not on an elephant track, and basically difficult even when in them, it was high enough to conceal an elephant unless it was very, very close, and seldom allowed more than the head to be seen even then.

Fortunately, the wind kept steady, but came in stiff gusts now and then, drowning the noise made when forcing one’s way through the rustling grass. But by the movements of the grass, ours were also concealed. Taking advantage of one of the gusts, I crept forward to a group of elephants and succeeded with the head shot. The elephants then moved back up the valley (i.e. downwind) and we struck out to find them again.

Having made our way to the edge of the jungle, we turned back to where our caravan was left. The men told us that the elephants crossed quite near them, and were just ahead of us. I crossed over to the opposite hill to get a better look at the valley and saw some moving about. Three came close enough, but while I maneuvered the glasses to see which had the best tusks, they moved away again. Climbing down to get closer, and even with the wind lying low, we could not see through the dense jungle. To creep through a low tunnel in the tangled mass, to right under an elephant’s nose, when it is on the lookout and is bound to hear you coming, is not likely to be pleasant, nor healthy. So while I hesitated, they were off again. On returning to the caravan, I saw a small group of females and let them pass, after all, I had a couple of elephants down. My rifles were a Lee Metford and a 10-bore Holland. Both had done their work well (my favorite .577 was absent on this outing). We camped and waited for the men to come in with some elephant meat.

It was strange country (no white man had ever been here) and satisfied my craving for untouched nature. The contrast between the green, damp valley and the dry barren hills was marked and curious. Lots of stuff might grow here were it not for the heat and mosquitoes. We followed the spoor of the retreating herd, alternately wondering whether it would be wiser to continue after the herd or return to camp. Soon after deciding to carry on, we came to a spot where several, but not all, of the herd stopped to drink. As we advanced, there was more and more spoor, not only of yesterday’s travelers but also of other stragglers that had been wandering at will. I was glad we had not turned back. There was a mimosa forest where the trees had been wrecked by elephants and the shrubs were distorted and crippled. And as we climbed another ridge, a marvelous sight met our view.

It was strange country (no white man had ever been here) and satisfied my craving for untouched nature. The contrast between the green, damp valley and the dry barren hills was marked and curious. Lots of stuff might grow here were it not for the heat and mosquitoes. We followed the spoor of the retreating herd, alternately wondering whether it would be wiser to continue after the herd or return to camp. Soon after deciding to carry on, we came to a spot where several, but not all, of the herd stopped to drink. As we advanced, there was more and more spoor, not only of yesterday’s travelers but also of other stragglers that had been wandering at will. I was glad we had not turned back. There was a mimosa forest where the trees had been wrecked by elephants and the shrubs were distorted and crippled. And as we climbed another ridge, a marvelous sight met our view.

Stretched below were cows, calves, small bulls and then – two massive bulls. Never before had I been able to see so many elephants in dense wood. Slowly, we descended into the thorn forest heading to where we had last seen the elephants but of course could see them no longer (though the wind was still in our faces). Soon we came up to a large herd loitering in and around a stream. Such a sight reminded me of the earlier books on the South African game herds.

In the midst of this work, the crashing of elephants first in one direction, then in another, I fired a shot at a close elephant and ran to try to cut it off along a path when my guide called my attention to noise made by another portion of the herd, on the other side of us. Being deaf in my right ear, I am unable to tell the direction from which a sound is coming and have to trust my men. I ran as fast as I could to the point indicated and came to a slightly more open but still narrow path where I could see bushes swaying and elephants here and there. I was watching them run when I heard an ear piercing, shrill close by. It sounded angry. I stood still, trying to figure out where I could shoot when I felt a tap on my back. Then, turning my head, I found myself face to face with an elephant, its black head and gleaming tusks just above me. It must have been running along the path I was in, screaming at seeing me in the way, and giving me a tap to see what I was perhaps before making pulp of me. I threw up my rifle, and myself back at the same moment, and it sheared off through the bush, after the others. I was not hurt at all and concluded that it was with its trunk, not its tusk that it gave me the pat.

Then, as I paused, a cow and one large bull moved about, crossing trunks (an elephantine kiss). I hesitated so much that my gun bearer crept up to my elbow and whispered, “Bwana, pika.” (Master, strike.) Indeed, that big one was what I had come for. I was about 50 yards away, and might have gotten closer but some of the elephants were moving into the dense bush across the stream. I singled out the bull with beautifully symmetrical and fairly long tusks and fired at him, aiming just behind the shoulder. At the shot, he started off, throwing a quantity of water out of his mouth. I hastened to give him a second shot before he reached dense cover. Then, seizing the magazine rifle, I fired another shot just as he was entering the bush. The bull died before it reached dense cover.

This was surely an exciting afternoon, filled with many incidents. On returning to camp I did what I always considered my first duty after a hunt, namely to clean my rifles. Then I had a dip in the river, some soup, and turned in about 3 a.m.–selected and edited by Ellen Enzler-Herring of Trophy Room Books