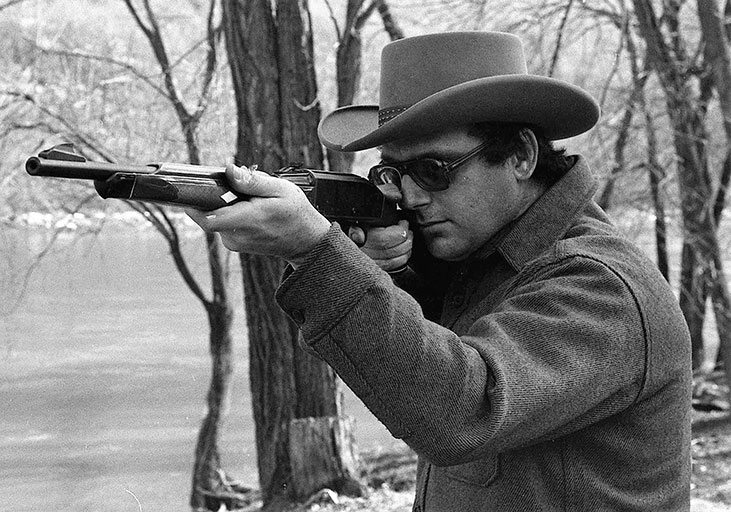

I was waxing nostalgic the other day with a friend about how many great guns have passed through my hands over the 55 years since I sold my first article and the fact that so many of them no longer exist.

Some of those guns achieved a high degree of popularity, while others shined but briefly. Some bit the dust decades ago, while others faded just recently. So many come to mind that I couldn’t possibly cover them here even briefly, but for starters five come to mind and three came out of Remington’s Ilion factory– the Model 591 rimfire rifle; the Nylon 66, also a rimfire, and the Model 788 centerfire.

What makes the 591 so memorable was not so much the rifle itself, but the cartridge for which it was specifically designed: the 5mm Rem. Rimfire Magnum. Way ahead of its time, the 5mm RRM debuted in 1969 and was derived by necking down a .22 cal. blank cartridge case that Remington was making for Hilti, a power tool company. The resultant cartridge launched a 38-grain Power Lokt HP bullet at 2,100 fps. It was the first bottle-necked rimfire cartridge to launch a semi-jacketed bullet. It was superior ballistically to Winchester’s .22 Magnum and was far more accurate, yet Remington discontinued 591/92 production after just five years. Why kill it when it was the fastest and most accurate rimfire cartridge on the planet? Couple of reasons: it had a larger rim diameter than the .22 Magnum and required a major redesign of existing rimfire rifles to accommodate it. With no other gun makers adopting it, and the fact that 5mm ammo was considerably more expensive than .22 WMR fodder, combined to kill what was an excellent cartridge, even by today’s standards.

Though Remington ceased 5mm ammo production long ago, all is not lost. If you’re lucky enough to own the tubular magazine 591, or the detachable box 592, Aguila, the Mexican ammo manufacturer, offers two 30-grain 5mm RRM loads, both of which exit at 2,350 fps.

To say the Nylon 66 was (is) a truly iconic firearm would be understating the case. Introduced in 1959, Remington would produce more than a million of what is surely one of the most visually distinctive and innovative rifles ever designed. At the gun’s inception, Remington was a subsidiary of DuPont Chemical so they went to the parent company to see if they could come up with a polymer around which they could design a rifle.

Did they ever! What looks like a two-piece stock separated by a steel receiver is nothing more than a cosmetic sheet metal cowling designed to hide the fact that, except for the barrel and bolt assembly, the 66 is one piece of plastic, if you will, from butt to forend tip. The bolt reciprocates on rails integral with the stock and requires no lubrication. The gun was so reliable that over a period of 13 days in October of 1959, Remington’s exhibition shooter, Tom Frye, using two Nylon 66s, managed to hit all but six of 100,010 wood cubes thrown in the air!

I don’t know which is more remarkable, the incredible skill and endurance of Tom Frye, or the mind-boggling reliability of the Nylon 66. And we don’t know whether Tom’s six misses were actually misses or six malfunctions, but either way it’s an astounding record that isn’t likely to be broken.

Over the 30-year production life of the 66 during which 1,000,350 were produced, several passed through my hands. To this day I regret that I didn’t have the prescience to buy at least one of them.

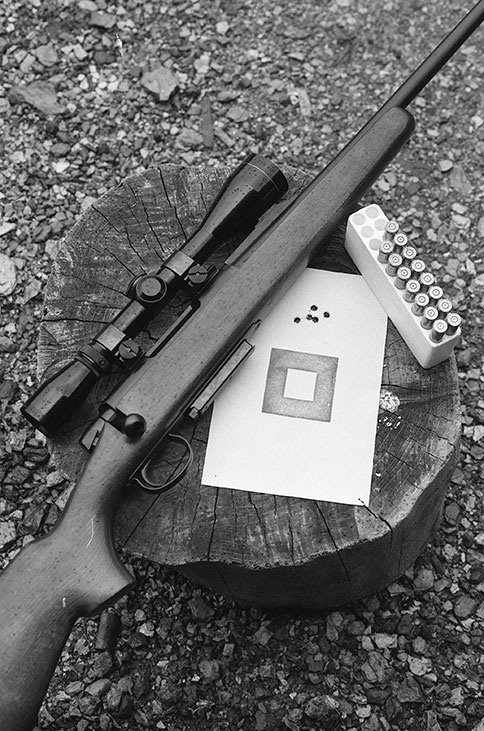

Remington’s 788 was a homely gun at best; it had a hardwood stock shaped into a lame rendition of a Monte Carlo, no color or figure whatsoever, and no checkering either cut or impressed. As for the receiver, there was no attempt to make it look like anything but what it was, namely, a pipe, with a minimal-size ejection port. The supplied iron sights were plastic, and the detachable magazine and trigger guard bow were of stamped sheet metal.

And last but not least, the 788’s locking system was to the average guy, all wrong. Instead of having two locking lugs up front at the head of the bolt like any “normal” gun is supposed to have, there were nine tiny locking lugs at the back of the bolt. Is nothing sacred?

Remington’s rationale for the 788 was to have a rifle that competed with the value-priced offerings of Savage and Mossberg, and as such was priced low enough to not compete with the company’s flagship Model 700. In other words, it was targeted to a different segment of the market.

Trouble was, that’s not how Joe Average saw it. The word spread quickly that the 788 on average was more accurate than the 700, to the point that benchrest shooters were buying the gun and using the action on which to build competition rifles. I could be wrong, but I think Remington discontinued the 788 because it cut too deeply into its 700 sales. Over its production life of 16 years from 1967 to 1983, some 565,000 guns were produced.

Today, on gunbroker.com, 788s in select calibers are listed with starting bids of $1,700; that for a rifle that originally sold for a little over $100 new. One of the test guns sent me back in the day chambered in 7mm-08 was so accurate that I had to buy it. Unfortunately, I was dumb enough that years later I let a determined friend talk me out of it.

When it comes to lever action .22s, Marlin’s 39A would probably win hands down as the most celebrated, but to my mind the best example of that genre was Winchester’s Model 9422. This is one gun I was smart enough to hang on to!

Designed to look as much as possible like the company’s iconic big-bore Model 94, the 9422 was surely one of the highest quality Winchesters ever produced. The receiver is a beautifully machined forging and the bluing, fit and finish of metal and wood was outstanding, to the point where it was probably the reason the gun was discontinued in 2005 – it became too expensive to maintain its established production standards.

I mean, there is a certain ceiling as to how much a .22 rifle can sell for, even one of this quality, and the 9422 just may have reached it. Nevertheless, from its debut in 1972 to 1991, some 600,000 of these guns were produced. There are no production figures I could find from `91 to `05, but at least 800,000 total has to be a realistic number. With there being so many of these guns out there, finding new and used ones online is no problem. Originally chambered only in .22 LR, the 9422 would eventually be offered in .22 WMR and .17 HMR, a tribute to the strength of the basic design.

A more recent demise and one that really breaks my heart is the passing of the Montana Rifle Co. and its superb Model 1999 bolt action. I own four of them. It’s not so much the passing of the rifles themselves that I lament, but the actions — the short, standard and double square bridge magnum. All four of my rifles are based on the short action, which along with the short Winchester Model 70, can accommodate cartridges loaded to 3.12” overall length. There are so many short-action cartridges handicapped because they are loaded to fit 2.8” magazines!

With the exception of the bolt stop/release, the Montana action looks like a clone of the Winchester, but closer examination reveals several subtle differences, all of which I consider improvements. The locking lugs are pie-shaped in cross-section — dovetailed if you will — with raceways to match. The result is more lateral stability to the bolt, a smoother glide, and less tendency to bind.

Gas venting in the event of a pierced primer or case head separation is also better on the `99. There are two large 1”x1/4” vent holes in the bolt body, and the flange at the front of the bolt shroud is wider to better seal the left lug raceway to block particle-bearing gases in the event of a pierced primer or case head separation.

And there is a vent hole on both sides of the receiver ring. And lastly, the Montana action retains the inner, annular ring of steel within the receiver ring against which the barrel breech abuts, just like on the `98 Mauser, and is interrupted only by the extractor cut. All are subtle changes, but they combine to make for a superior controlled-round feeding action.

The Montana Rifle Co. has been no stranger to financial ups and downs since opening its doors in 1999, and I hope that someone or group will come to the rescue. They just had too good a product to let die.–Jon R. Sundra