When A Mountain Lion Hunting Guide Saw Spots

The saga of a Jaguar surprise – and then some…

Hunters hunt because that’s what we do and who we are. When we hunt, we are part of nature rather than simply observers of it.

Warner Glenn is a hunter, a guide. And he is a whole lot more. He has a vision of open lands where ranching and wildlife can abound forever. He also is the first person to find and then photograph a live, wild jaguar in the U.S. – an honor he has since repeated.

Jaguars are not hunted in southern Arizona where Warner calls home. Field researchers using trail cameras were the first to detect jaguars in the Huachcuas and Dos Cabezas mountains in 2016. Sportsmen detected those seen in recent history prior to 2016.

Adventure abounds where few outsiders ever go. Hunting is as much a part of the social landscape in this region as are rocks, sand and sun to the physical environment there.

This is a story about big cats, hound dogs and hunting. It’s about the desert Southwest and a ranching/hunting culture that is known, but not really well understood, elsewhere in the world. It’s about Warner Glenn, the larger-than-life rancher whose persona ties them all together.

Warner Glenn does all of this in what many might consider to be a totally inhospitable environment. The piercing summer sun and searing temperatures are so overbearing that even flies pester only the shadowy side the face. Winds are hot in summer, cold in winter and always uncomfortable. Extremes are the rule. Everything is hard, sharp or gritty. Yet all of these challenging elements produce one of the most breathtakingly beautiful settings imaginable.

Legends abound in the distant reaches of the dry, dusty Southwestern United States. Many of these tall tales focus on gold – Aztec gold, gold of the conquistadores, even lost mines with big nuggets or glittering flakes of gold dust carpeting dry river beds.

Far-fetched yarns of outlaws and their gangs, the exploits of Geronimo and other Indian uprisings, or the toils of early ranchers trying to scratch a living out of the hostile environment all play into the lore in such a way that separating fact from fiction is often impossible and usually not even desired. Truly, this WAS the wild west. For the most part, it still is.

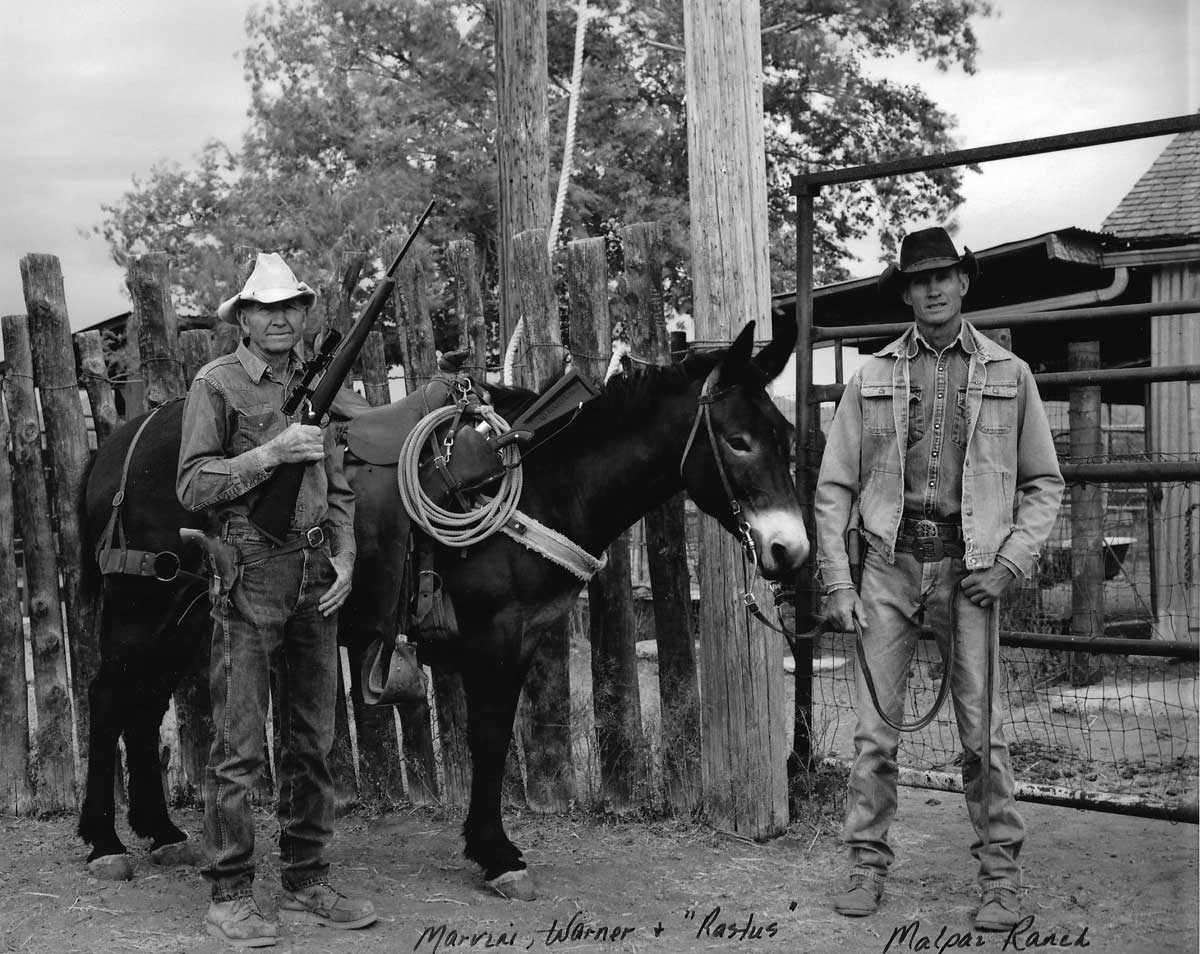

To get to Warner’s Malpai Ranch, just head east out of storied Tombstone, Arizona, where Wyatt Earp and his brothers made Western history in the long ago. Keep going a fair distance until you come upon a dirt driveway on the left of the unpaved road. If you go past a bushy mesquite on the right, you went too far. Generally speaking, this area is where Arizona, New Mexico and Mexico converge.

Up that driveway two miles is the headquarters for the Malpai Ranch, and home for Warner Glenn. Warner’s a true rancher and cowboy in the classic senses of the terms. But that’s not the subject here. For this discussion, Warner is a houndsman, who with his dogs, mules and daughter guides for mountain lion hunts.

Hunters sometimes encounter the unexpected while in the wilds, and this is a story about how Warner Glenn happened upon a jaguar while hunting for lions. This part of Arizona is not what one would consider to be jaguar habitat. Jaguars are creatures of the tropics, not of the desert.

Since only male jaguars have been spotted and/or photographed in recent times in southern Arizona, it is apparent that they are really just passing through. Some folks opine that these jaguars have been pushed out of their normal range south in Mexico by other more dominant jaguars there.

All of that, however, has been in recent years – long after the Glenn family moved to the area that was then part of the Arizona Territory (didn’t become a state until 1912) in the late 1890s from Texas – several decades before Warner, now in his 80s, was born.

Warner Glenn is the real deal. He’s tall, soft-spoken and as solid as the rocks that comprise much of the landscape around him. Literally, he is OF the land in which he lives, ranches and hunts.

He has guided hunters from all backgrounds, both famous and not so much so. Among them was Keith Bates of Chicago, who helped found SCI and who served as the first editor of Safari Magazine.

Warner reckons that there are more mountain lions in that area now than there were in the 1940s, 1950s or 1960s – more now than at any other period in his long lifetime.

“That is because there are no more bounties and there is less hunting pressure,” he explains.

Certainly, the results from legal lion hunts that are reported to the Arizona Department of Game and Fish reflect both a healthy population and consistent take of mountain lions year after year.

For example, in the department’s Unit 33, which includes the Rincon and Catalina Mountain areas, hunters have taken an average of 22 lions per year.

For example, in the department’s Unit 33, which includes the Rincon and Catalina Mountain areas, hunters have taken an average of 22 lions per year.

Even with healthy mountain lion populations, it takes a lot of hunting to get a lion in this remote area. Typically, on such a hunt, Warner explains that they hunt all day and then use a base camp at night, sometimes at the ranch headquarters and other times out in the hills, depending on how things go on a particular hunt.

Mules, that are better suited for this kind of hunting than horses, are used one day and then rested for two, swapped out as needed.

There is no need for long-range rifles and cartridges in this kind of hunting.

“Usually it is close shooting,” Warner notes. Depending on the terrain, long shots are 100 yards, maybe more, often much less. For these lions, .30/30 lever-action saddle carbines or even .357 magnum handguns are fine. These are true free-range hunts.

Within Warner’s hunting territory is the Peloncillo mountain range that stretches from Cochise County, Arizona and Hidalgo County in New Mexico, southward into Sonora, Mexico. It was there, in 1996 while Warner and daughter Kelly were guiding a mountain lion hunt, that Warner became the first person to spot and then photograph a jaguar in New Mexico.

The last Warner saw of that jaguar, following some close encounters with Warner’s dogs, the big cat was headed south toward Mexico, which was only a few miles away.

Ten years later and 20 miles away, Warner found and photographed another jaguar. Since then, jaguars have been photographed by trail cameras at various spots around southern Arizona, and always they have been lone males.

Arizona Game and Fish Department officials have been able to learn quite a lot from all of the photographs, because each jaguar has a unique pattern to its spots – unique in much the same way as humans each have unique fingerprints.

Raul Vega, AZGFD Regional Supervisor for Region V in which all of the jaguars have been spotted and/or photographed on trail cameras, explained that it seems as though the jaguars have used three major mountain/valley corridors on their trips into Arizona.

Best evidence is that in one corridor the Dos Cabezas jaguar migrate north through the Chiricahua Mountains, which are near but disntict from the Peloncillos Mountains near the New Mexico and Mexico borders, the second corridor is in the Huachuca and Whetstone Mountains/San Pedro River area and the third corridor is in the Baboquivari Mountains. That entire area lies south of Interstate 10, although historically jaguars had extended as far north as the Grand Canyon.

It is not surprising that Warner Glenn would be the first person to find a jaguar in Arizona since he spends most of his time out in nature. Petroglyphs in that area and throughout southern Arizona witness what life was like before “recorded” time, and hunting has been a part of human existence there all along.

It is not surprising that Warner Glenn would be the first person to find a jaguar in Arizona since he spends most of his time out in nature. Petroglyphs in that area and throughout southern Arizona witness what life was like before “recorded” time, and hunting has been a part of human existence there all along.

As part of the hunting and ranching culture, Warner and his family are involved in efforts to assure that there is a future for wildlife. They are part of the Mapai Borderlands Group, which spells out its mission: “Our goal is to restore and maintain the natural processes that create and protect a healthy, unfragmented landscape to support a diverse, flourishing community of human, plant, and animal life in our borderlands region. Together, we will accomplish this by working to encourage profitable ranching and other traditional livelihoods which will sustain the open space nature of our land for generations to come.”

Total details of Glenn’s first encounter with a jaguar are included in the book entitled: “The Life and Times of Warner Glenn” by Ed Ashurst, and in a separate publication “Eyes of Fire/Encounter with a borderland jaguar, a story and photographs by Warner Glenn.

In the preface to “Eyes of Fire,” Warner explains the day that he first encountered a jaguar in the wild:

“This story is about an incident that happened on March 7, 1996, the fourth day of a ten-day mountain lion hunt that Al Kriedeman booked with us. We were staying at our home, the Malpai Ranch, in the San Bernardino Valley of Arizona, and we were driving each day to the mountains to hunt.

“Kelly, my daughter, was guiding with me….”

Glenn then explains in detail what led up to first modern sighting of a jaguar in Arizona, and recounts that magical moment when the mountain lion he thought he was tracking actually had spots.

“Looking out on top of the bluff, I was completely shocked to see a very large, absolutely beautiful jaguar crouched on top, watching the circling hounds below. I had never seen one of these animals in the wild – only once in a zoo. I was stunned by the surprise and beauty of the scene. This was a first for me. I had been 60 years waiting to see this beautiful creature. I said out loud to myself, ‘God Almighty! That’s a jaguar!’”

As is often said: the rest is history.

In such a timeless setting, time does go by for Warner and his family. Kelly continues to help.

The ranch headquarters is more like a museum of the desert Southwest than anything else. Photos of the family over the generations cover the walls, while artifacts of the Western culture, including many Native American items, are everywhere.

There also are numerous photos of Kelly when she was featured in a number of advertising campaigns by Sturm, Ruger & Co. Yes, Kelly is still “The Ruger Girl” in the ads. And what better subject? She knows guns and how to use them.

Also on hand during a recent visit to the ranch was Kelly’s daughter, Mackenzie Kimbro. In her book, “Roots Run Deep, Our Ranching Tradition,” Mackenzie notes:

“Mom became ‘The Ruger Girl’ in 1988 because she was a 5th generation rancher and a 3rd generation hunting guide. They wanted someone to represent family and tradition….”

In the end, it is our tradition that separates hunters from the rest. Since the beginning, it has been that way. For Warner, Kelly and Mackenzie on the Malpai Ranch where the spirit is eternal, it always will.

Hunters hunt because that’s what we do and who we are. When we hunt, we are part of nature rather than simply observers of it. Hunter Pride.–Steve Comus