Blaser, Mauser and Sauer Continue Their Unique Legacies in the Blaser Group

By Wayne Van Zwoll

Three names — Blaser, Mauser and Sauer — represent Europe’s best-known repeating rifles. Horst Blaser, Peter Paul von Mauser and Lorenz Sauer hung out their shingles at different times, but the resulting companies are now distinct brands under the umbrella of the Blaser Group. They all share an industrial campus served by 700 employees near Isny, a quaint city of 15,000 people in southern Germany.

Minox and Liemke optics also belong to the group, as does Rigby, the London-based company that uses 98 Mauser actions for its bespoke magazine rifles. The Blaser Group is owned by L&O (Luke and Ortmeier) Holding Co., which also controls SIG Sauer.

The Blaser Group now has subsidiaries in 11 countries. Blaser USA, under CEO Jason Evans, operates from San Antonio, Texas. In Isny, Christian Socher is CEO of Blaser GmbH. Last fall I visited him and his team for a company update.

Matthias Klotz, CSO at J. P. Sauer and Mauser operations and sales director for all three manufacturers, was not on site; but Thore Wolf, a brand manager for Mauser, and Marcus Ress, who oversees J.P. Sauer stateside, were most helpful.

J.P SAUER & SOHN

Established in 1751 as a maker of fine sporting arms, J.P. Sauer & Sohn grew through tumultuous times, including two world wars. Among its most famous products is the Model 30 Drilling (from the German drei for three). Its hinged breech seats twin 12-bore shot barrels over a 9.3x74mm rifle barrel.

The design and craftsmanship suggest a top-end sporting gun, but the M30 was designed as a survival tool for pilots. The narcissistic Hermann Göring, head of Germany’s Luftwaffe but also Reichminister of Forestry and an avid sportsman, ordered these guns from J.P. Sauer with military funds early in World War II, when the Reich’s fortunes were still ascending.

Some M30s almost surely became gifts to advance Göring’s career. Most of those issued rode in Ju 87 Stuka dive bombers and Messerschmitt Bf 109 fighters during the North Africa campaign. Their aluminum cases also held 25 shotshells and 20 each of slug loads and 9.3×74 cartridges with soft-point bullets forbidden by international law to use in battle.

The Model 30 was cleverly engineered and beautifully finished, with a checkered walnut stock and case-colored frame. Nudging the tang switch ahead raised a rear sight and set the triggers to fire the rifle, then the left barrel, choked for Brenneke slugs. Thumbed back, it readied the shot barrel first. Only 2,500 of these Drillings were built, all between 1941 and 1942.

Now Sauer lists two series of hunting rifles, both bolt-action. The six-lug 404 comprises nine sub-models, eight with iron sights. It features a cocking switch for safe loaded-chamber carry. Interchangeable bolt heads and barrels serve 15 chamberings.

Sauer’s 101 is the company’s mid-level rifle. This one in 9.3×62 has an excellent trigger, a finely checkered walnut stock proportioned for fast aim with its open sights or a low-mounted scope.

The affordable three-lug Sauer 100 includes 11 sub-models, stocked in beech, walnut, laminates and synthetics. It has a three-detent safety and an adjustable trigger. Fieldshoot and Pantera versions were the first commercial rifles barreled to 6.5 PRC. My similar 101 (now discontinued) is beautifully fitted, points naturally and drills 1-inch knots with 9.3×62 factory loads.

“Sauer firearms are noted for their, well, elegance,” said Marcus Ress. “Not adherence to fashion, but insistence on quality. During its first century, hunting was limited to nobility, men of discriminating taste.”

The company was first to advertise Krupp steel, a name soon seized upon as a mark of distinction. J.P. Sauer’s current offerings include a sidelock shotgun whose $60,000 price reflects not only the fit and function of its components, but its trim, traditional form, the detailing of wood and steel, the quality of its walnut and its impeccable finish.

Technicians and artisans work side by side to build R8 Blaser rifles, exceptional in function, finish.

PAUL AND WILHELM MAUSER

In 1867, a failed bid to supply France a service rifle sent brothers Paul and Wilhelm Mauser back to their native Oberndorf, where they opened a gun shop. Then, impressed by a Mauser rifle from another source, the Royal Prussian Military Shooting School suggested they improve it. The Mausers did. Their 11mm rifle of 1871 became Prussia’s infantry arm.

Seven years after Wilhelm passed in 1882, Fabrique Nationale d’Armes de Guerre, or FN, began building Mauser Model 1889 rifles for the Belgian government. The 1889 established Paul Mauser as Europe’s premier gun designer.

In his Model of 1892, Paul introduced his celebrated non-rotating extractor. Collared to the bolt, it grabs the case early, controlling its travel into the chamber. The husky claw frees reluctant empties and clears the breech even if the shooter short cycles.

Within a year Paul replaced its single-stack magazine with a flush, staggered-column box. The 1893 Spanish Mauser was adopted by armed forces worldwide. Sweden’s 1894 order of 1,200 carbines would prompt production of Mausers in 6.5×55 by Carl Gustaf’s Stads Gevarsfaktori, a government arsenal.

Improvements on 1893 and 1895 Mausers yielded the cock-on-opening 1898 action, approved by the German Army in April that year. The original Gewehr 98 was soon bloodied in the Boxer Rebellion. It would serve many nations in many conflicts. Paul Mauser died in May 1914, just before his rifle shared the horror of the trenches in World War I.

After WWII, Mauser entered the sporting trade. U.S. agent A.F. Stoeger, of New York, assigned numbers to the various ’98 actions. By the end of the depression there were 20 types in four lengths. At that time, a Winchester M70 cost $61.25 and Mausers could fetch considerably more!

Cloned ’98 actions blessed the custom rifle trade. In 1995, the Rheinmetall Group acquired the Mauser werk. Mauser Jagdwaffen GmbH was set up the next year to build Model 98 rifles at Isny. The switch-barrel Model 03, now discontinued, preceded the more traditional and affordable M12. The value-priced, but well-engineered M18, followed.

“In Germany, the image of Mauser sporting rifles evokes campfires in wild, rugged places,” said Thore Wolf. “The 1898 action is strong, simple and reliable. We consider the Models 12 and 18 modern versions of the original ’98 — perhaps what Paul Mauser might have designed with current tooling, labor, markets and budgets.”

He added that the five-axis CNC machines that now automate rifle production don’t like the ’98. “It was designed with skilled labor and 19th century shop tooling in mind.”

What of Isny’s current Model 98s? “Ah, they’re luxury items,” he replied, “for connoisseurs who know their history, value tradition and appreciate fine machine work and fancy walnut.” Wolf said that of all the Model 98 chamberings available in the U.S., the .375 H&H is their best-seller.

In Europe, Mauser and Sauer rifles bored to 8×57 remain popular, various magnums snapping at their heels. Oddly, Thore said the 7×57 is “just about dead.” The caliber is not even offered in M12s and M18s stateside. The .308 and .30-06 have overtaken the 7×64 and the 9.3×63 in many markets. Thore said he suspects it’s because they’re available with lead-free loads. The 6.5 Creedmoor and 6.5 PRC are popular on both sides of the Atlantic.

HORST BLASER

The company founded by gunsmith Horst Blaser in 1957 has since distinguished itself with truly innovative rifles and shotguns. The first was his over-and-under “Diplomat” combination gun. As he lacked tooling to manufacture it, many components were built in the gun making center of Ferlach, Austria.

By 1960 Horst had redesigned the Diplomat so he could do all the work except drilling the bores. The Blaser Model 60 was Germany’s first hunting rifle produced almost entirely by machines. It sired the ES 63, the “ES” for Einschloss or single lock. The 63’s big receiver and monoblock served many cartridges. Within two years, Horst designed a scope mount for it.

In 1967 the ES 67 offered even more chamberings. The ES 70 followed, with the company’s first interchangeable barrels. Blaser’s 1970 catalog appeared in English as well as German.

The next year Blaser introduced its Model 71 single-shot rifle, with a manual cocking device. Its single-stage trigger was touted as being as good as a traditional set trigger. With strong sales and a staff of 40, Horst Blaser built a factory near Isny.

In 1975 he introduced the B75 Bergstutzen over-and-under rifle on the ES 70 action. Barrel regulation at the muzzle nixed the costly soldering alternative. Blaser’s scope mount had become the most popular in German-speaking countries.

In 1977 the single-shot rifle gave way to the K77, a fresh design with a tilting breech-block. Four years later came a new over-and-under rifle, the B810, also with a tilting block. The B820 joined it. Costly to produce, this series would last eight years.

During the 1980s, Blaser was among the first rifle manufacturers to use CNC machines. In 1983, the company fielded its first bolt-action rifle.

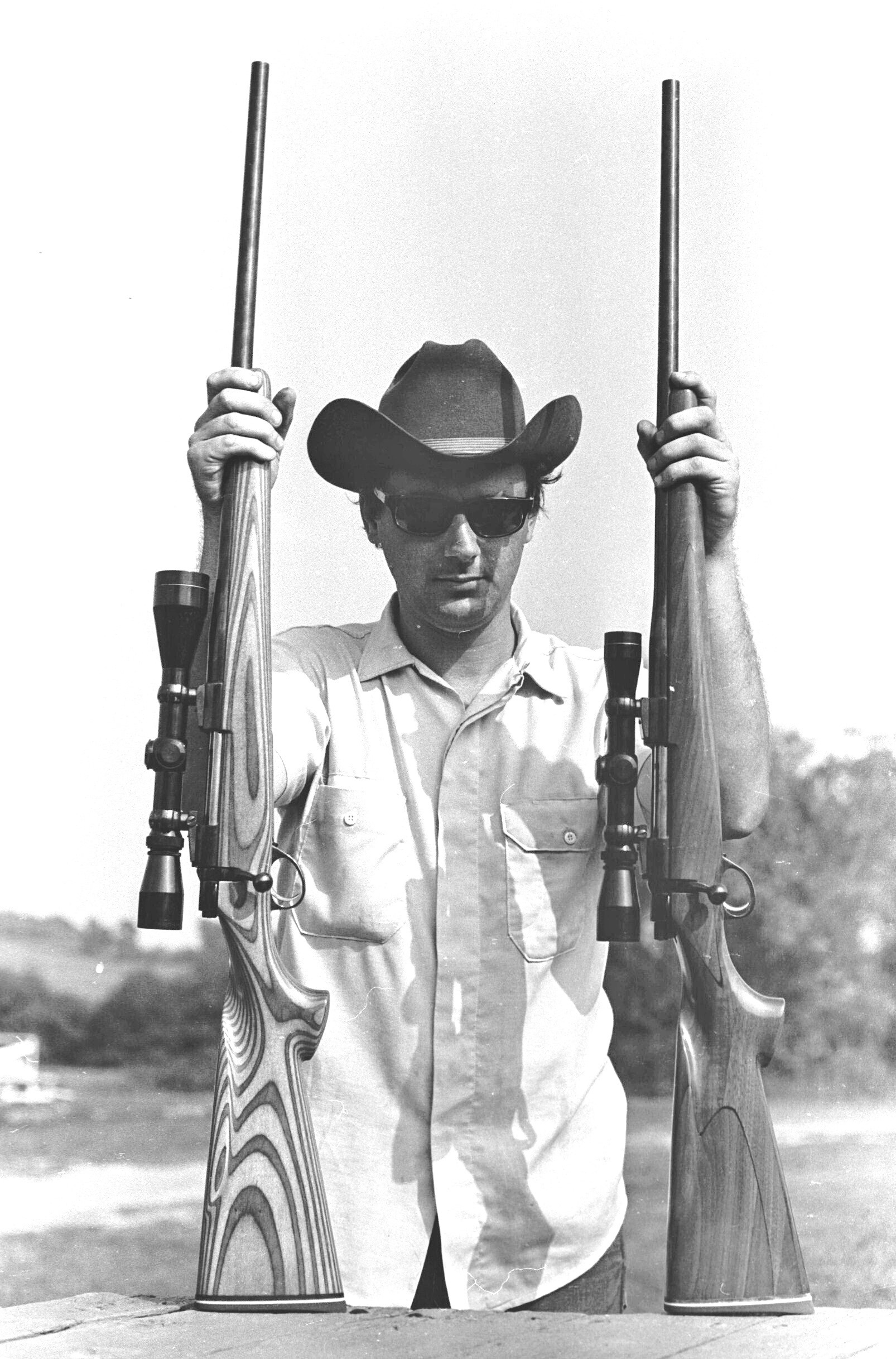

Unlike most turn-bolts, this was not a refined infantry arm, but an innovative repeater that caught the eye of Gerhard Blenk. An avid hunter then working in the Texas oil fields, Blenk proposed exporting the Model 830 to the U.S. It became Blaser’s Ultimate and later the R84.

The next year Horst Blaser decided to sell his company to Blenk, who had returned to Isny. During the next 15 years, Blaser Jagdwaffen grew to become Germany’s premier gun-maker. Its payroll doubled. Its engineers fashioned a Bergstutzen over-and-under rifle in chamberings to .375 H&H, also a three-barrel Bockdrilling. Other models were dropped; the SR 850 bolt rifle sold well.

German ammo-maker RWS helped develop the .30 R Blaser cartridge. The K77 added Ultra Light and All-Weather (nickeled-barrel) versions. In 1995, this popular single-shot would be replaced by the similar K95.

Blaser continued designing and building shotguns. An autoloader I viewed in prototype stage died mercifully soon thereafter. But over-and-unders have fared better.

According to Christian Socher, Blaser sells 3,000 to 4,000 F16 and F3 shotguns every year. An F16 that came to hand for an upland hunt tumbled fast-flying birds almost on its own.

A mediocre wingshooter on good days, I can’t recall another gun with the magic of that F16! At $9,000, the F3 commands double its price, but outsells it. “They’re both quite expensive,” Socher pointed out. “Many of the shooters who’d consider either are clay target competitors. They want to win. The F3 is the gun to beat in major events.”

The most important Blaser development during Blenk’s tenure was a straight-pull rifle introduced at the International Weapons Exhibition (IWA) show in Nuremberg in 1993.

Designed for long-range shooting, this Blaser R8 in .338 Lapua has a special magazine, stock and bolt knob.

Designed by Blenk and R&D chief Meinrad Zeh, the R93 was the first Blaser rifle to also debut in the U.S. Its bolt locked radially, fingers of an expanding collet on the bolt head forced outward to engage a circumferential groove in the barrel.

The bolt assembly telescoped, and the magazine was tucked into a compact trigger group. The R93’s action was a couple of inches shorter than those of ordinary turn-bolts. Interchangeable barrels, bolt heads and magazine inserts suited this rifle to a wide range of cartridges.

Rifling and most chambers were hammer-forged, and scope mount recesses were cut precisely in the hardened barrel surface to ensure return to zero when scopes were removed and replaced.

While the R8 rimfire bolt differs in many ways from the centerfire, bolts interchange without tools!

The R93 is safe to carry with the chamber loaded because the thumb-switch on its tang is not a safety. It cocks and de-cocks the rifle. Pushing the switch ahead readies the rifle to fire. Another nudge, down slightly, lets the switch return to the original de-cocked position.

The bolt knob resembles those on turn-bolt actions but doesn’t lift. A tug after firing swings it to the rear, unlocking it. Continued, that pull extracts and ejects the case. A push chambers the next round. Lightning-fast to cycle, the R93 requires no attention to the thumb-switch between shots.

Introduced in 2008, the Blaser R8 functions the same way. But it is even stronger, with a steeper locking angle (90 degrees instead of 50) and a bushing that adds support to the collet after lock-up.

In lab tests the R8 endured pressures of 120,000 psi — nearly twice the SAAMI pressures for many modern high-velocity cartridges. “Gauges failed before the rifles did,” an engineer told me.

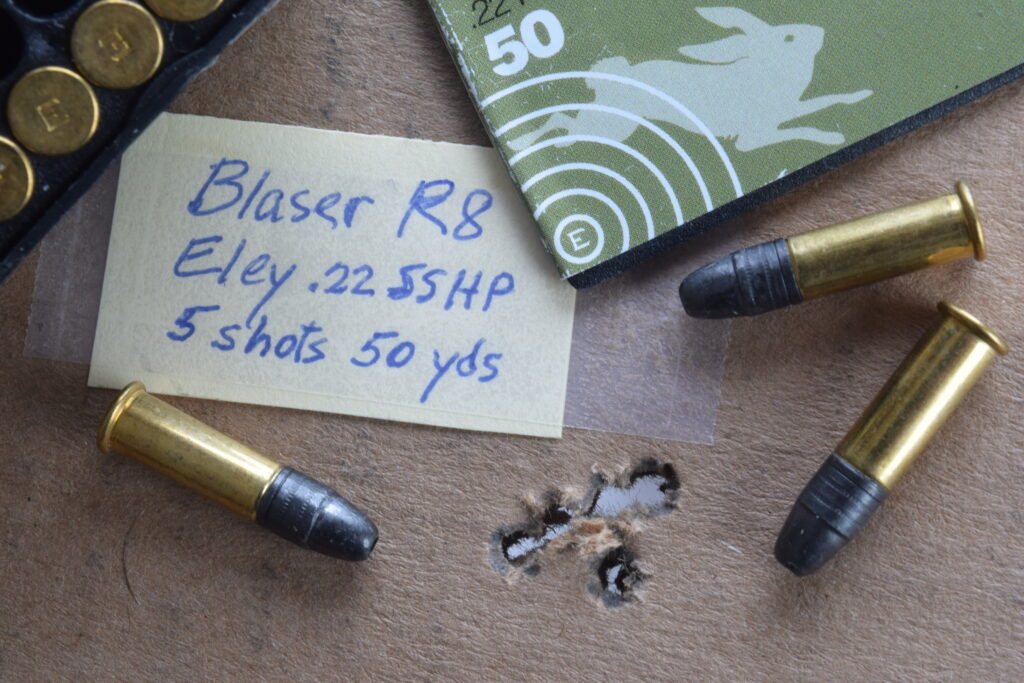

Blaser is now offering rimfire kits for its R8. This 50-yard group is one of several proving that with good ammo Blaser’s R8 in .22 LR will consistently ding pennies to 75 steps.

Another change: The R8’s trigger-magazine group is hand-detachable. A tab inside the box locks it in the rifle for easy top-loading. Removing the box de-cocks the rifle. Stocks (polymer and European walnut) have cast-off at toe and heel, even the grip, for quick, natural “Fifteen years after its debut, 80% of Blaser-branded firearms sold are R8s,” said Christian Socher. Sub-models have proliferated. Chamberings include the .338 Lapua, longer and larger in diameter than full-length magnum cartridges like the .375 H&H.

Clever Blaser engineers have managed to slip a short stack of these rockets into the R8’s trigger group! A factory-braked R8 GRS in .338 Lapua drilled 3/4 minute groups for me.

In 2012, the Professional Success arrived with a synthetic thumbhole stock. A walnut thumbhole followed. In 2016, when Blaser introduced the R8 Silence (defined by its barrel-length suppressor), leather pads appeared on the comb and grip surfaces of some synthetic-stocked sub-models. The Ultimate has an adjustable stock. “Thumbhole and leather-accented stocks have proven more popular that predicted,” said Socher.

For women, Blaser designed an R8 Intuition, whose shorter stock has additional cast-off. Barrel length and contour are suited to cartridges favored by small-frame shooters.

While Blaser’s stock-blank bins hold eye-popping walnut (much of it now from Bulgaria), pretty wood has become pricey. In Europe, even the K95, a purist’s single-shot whose heritage and profile argue for wood, sells best with a synthetic stock. “Hunters like its price and durability,” explained my host.

Fine walnut meets crisply shaped metal on this Mauser 98. The collar of the non-rotating extractor is visible.

Blaser has worked with RWS and other ammunition companies in cartridge development. One of the most appealing to me is the 8.5×55, a rimless .338 with the .532-diameter base of a belted magnum. It nips the heels of the .338 Winchester Magnum ballistically, but firing one of five factory loads, I found it less jarring. It’s essentially a strong .338-06, a superlative if under-sung elk cartridge.

“The 8.5×55 excels in 42cm (16.5-inch) and 47cm (18.5-inch) suppressed barrels,” said a Blaser engineer, handing me an R8 Silence. Recoil and blast from that short barrel was about like those from a traditional rifle in .243.

The R8 currently sells in 48 chamberings, .17 Hornet to .500 Jeffery. Europe’s most popular are the .308, 8×57 and .30-06 (In Germany big-game hunters must use bullets of at least 6.5mm diameter that bring 2,000 joules (1,475 ft-lbs) to 100 yards, and Austria’s minimums are 6mm and 2,000 joules). The best-selling R8s in the U.S. are .308s and .375s.

To me, the R8 is an engineering marvel with just one barrel. That it can jump from one cartridge class to another with switchable barrels, bolt heads and magazine inserts is astounding! Changes are easy. To swap barrels, just remove the bolt, loosen two captive forend screws with a supplied allen key and tug the barrel up and forward. Insert the new barrel, snug the forend screws and slide the bolt back in. Magazine inserts can be switched without tools. A small screwdriver to push a latch helps with the bolt-head change.

“Rimfire barrels posed new challenges,” said Christian Socher. “We met them.”

In .22 LR, .22 WMR and .17 HMR, these barrels suit any R8 receiver. Sight-free, they have the machined scope mount dimples of centerfire barrels. The rimfire bolt head has dual extractors. Six-shot inserts fit standard Blaser magazine shells. There’s no change in rifle function.

To see how Blaser had engineered these components for user-friendly changes, I requested a .22 LR kit. It came with a synthetic-stocked R8 in 6.5 PRC, and an R8 manual. Per instructions, I pulled the PRC barrel, inserted the .22 LR barrel and popped in a new magazine insert. The bolt-head swap was a bit more involved, but hassle-free. Voila! An understudy rifle for 3-cent cartridges!

The trigger pull did not change from its delightfully creep-free 2.1 pounds. I affixed a Burris 3-9x rimfire scope with Blaser rings.

Deep snow, high winds and single-digit temperatures made range trials a challenge as my SAFARI Magazine deadline loomed. At last, I grabbed some ELEY ammo and improvised a rest in the lee of a tree line.

Simple lines crisply rendered in top-grade walnut complement a traditional pad on this lovely rifle.

The reticle’s horizontal shuffle persisted. At least 3/8 inch, I thought. A magazine load of six shots punched a knot 1/4 inch high, 1/2 inch across at 50 yards. In fine weather over my Stukey bench, this .22 will surely prove a half-minute rifle. Now hunters can dodge the beating of surly hunting loads with a rimfire R8 barrel.

The R8 rimfire kit is not inexpensive at about $1,400. For its price you could buy a couple of serviceable .22 rifles. But if you think of the kit as a new R8, it’s the best rimfire bargain around.

Horst Blaser might tell you so. He still lives in his modest home next to the Blaser Mauser Sauer campus. The steady hum of production reminds him of what his Diplomat combination gun started 66 years ago.