Sudan, A Hunter’s Paradise Lost

By Charles “Chuck” Bazzy

This story originally appeared in the 2023 July/August edition of Safari Magazine.

Sudan, a land that once held profound wildlife diversity, continues to be decimated by conflict and warfare to this day. Author Chuck Bazzy shares his recollections of the greatest safari period in the history of the nation. It’s now, however, a hunter’s paradise lost.

Sudan once had a prolific wildlife population. It was subsequently diminished by colonialism, slavery, ivory-trade poaching, religious and civil strife, tribal wars and economic exploitation. To fully understand the cause and effect, it requires a brief knowledge of the geopolitical history of Sudan. The name Sudan was derived from the Arabic word “aswad,” meaning black, and consequently Sudan, “land of the black people.” In the early 1800s, Egypt controlled northern Sudan and the ivory and slave trade in the area. In 1882, the region came under British domination. Just prior to this, a nationalistic revolt led by Muhammed Ahmad Al Mahdi began to form and the Mahdi defeated the Egyptian army, establishing a theocracy in Khartoum, the capital city.

General Charles Gordon was sent to evacuate British loyalists from Khartoum but was defeated and killed by the Mahdi forces. The Mahdi ruled Sudan for approximately 14 years. In the 1890s, the British Lord General Herbert Kitchener led an army that defeated the Mahdi and regained control of Sudan. Britain and Egypt agreed on a joint government, creating an Anglo-Egyptian Sudan.

In 1930, the British civil secretary in Khartoum declared the Southern Policy and officially implemented what had always been in practice: the north and south, because of their many cultural and religious differences, are governed as two separate regions. For many years the south was governed as a restricted area and foreigners were not allowed to travel there without government approval to avoid agitating the southern tribes. Eventually, this restriction was lifted and foreign travelers were allowed to enter the southern provinces.

After World War II, Britain abruptly merged the north and south into a single administrative region. They made Arabic the language of the administration in the south, and northerners began to hold administrative positions there. Anticipating independence and fearing domination by the north, southern insurgents staged a mutiny in Torit. The rebels developed a large secessionist movement called the Anyanya, also known as safari ants.

On January 1, 1956, independence was granted to Sudan as a single unified nation. Up to this point, there was no organized safari or tourism business.

In 1961, I was contacted by Koepplinger Bakeries in Detroit, Michigan. They wanted to fund a new safari film in a remote part of Africa. The company would use adventure films for promotion.

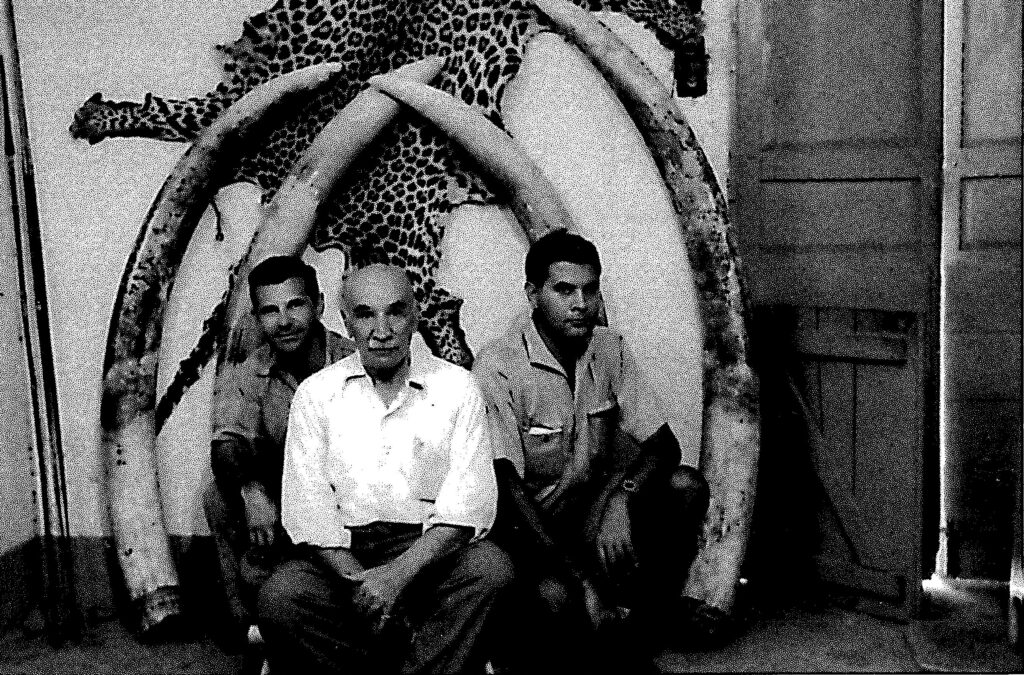

Being of Arabic descent, a Muslim and speaking both Arabic and Swahili, I was the right person for the job and Southern Sudan would be ideal for this safari. I contacted Abdul Aziz Oufan, Sudan Safari Tours in Khartoum and arranged a 14-day safari in Southern Sudan. I flew from Khartoum to Juba where I was greeted by Ali Oufan, brother of Azziz Oufan, who had a small office in Juba. The company had employed a young Syrian man to act as my professional hunter and guide. I eventually discovered he had shot a few buffalo but had never hunted elephants. My first act was to go to the Sudanese Game Department to obtain game licenses and permits. I was introduced to Senior Game Warden Mahmoud Abu Sinena and his lieutenant Ser Ahmed, who oversaw the southern provinces of Equatoria, Upper Nile and Bahr el Ghazal. At that time, Nile buffalo and lion were classified as vermin and no licenses or permits were required. Consequently, I purchased an elephant permit and permits for selective plains game. There were no licensed professional hunters in the southern provinces at the time. Lt. Ser Ahmed was assigned to accompany me on the 14-day safari to determine my experience and skill levels in hunting dangerous big game. Upon my return to town, I was introduced to Mr. Costis Yiamanis, a local merchant and ivory trader and his bookkeeper Angelo Dacey, who later became the premier professional hunter in Sudan.

After completing the outfitting for the safari, we crossed from the west bank to the east bank of the Nile by motorized ferry. From there, we traveled farther east, crossing the River Kitt into elephant country. Our safari camp was the usual tented camp with sleeping cots and basic cooking implements.

A game scout, Shawish (sergeant) Abdulla and trackers set out to look for elephant spoor. They returned shortly, having found a very large herd of bulls, cows and calves, not the ideal situation for hunting bull elephants. Walking at a brisk pace, we caught up with a very large herd of several hundred elephants, feeding on the move. There were many shootable bulls in the 60-pound class and some much bigger ivory. Unfortunately, the biggest tuskers were in the middle of the herd. I eventually shot an elephant with tusks in the 60-pound class.

Ser Ahmed, the game officer, left the safari while the rest of us traveled north to Mongalla on the east bank of the Nile and to the nearby village of Jabur where I set up camp. Not long after, a safari car pulled up and out stepped a tall man who approached and said, “My name is Tony Sanchez Arino and to whom am I speaking?” I introduced myself and invited Tony to join me for some refreshments. He indicated that he had a safari camp nearby with two Spanish clients, and they had expended most of their ammunition and he asked if I had any to spare. I gave him several boxes of cartridges, he thanked me and left. Little did I know that I would cross paths with Arino many times in different African countries in the coming years.

The next morning, a game scout came to my camp on a bicycle to inform me that a wounded Nile buffalo was at a nearby waterhole, threatening the villagers. The game officer requested that I kill it. Arriving at the waterhole, I saw the buffalo lying in the mud adjacent to the waterhole. It had been wounded in the right rear foot. As I approached, it got up and ran into a nearby thicket. I instructed my trackers to check the rear of the thicket to determine if the buffalo had exited.

Seeing no spoor, we concluded that the buffalo was still inside. I asked my trackers to throw lumps of dried mud into the brush to force the buffalo out. Almost immediately, the buffalo charged. I fired two shots into its chest and it dropped immediately. I measured the horns and eventually found that this was the No. 1 SCI Nile buffalo in the SCI Record Books. It remained in that position for many years.

The distribution of wildlife in Sudan is unique as compared to other African nations. The country is divided geographically east and west by the Nile River and topographically south and north by the tropical region south of Malakal and the arid region north to the desert and the Red Sea Hills. On the east bank of the Nile the fauna is somewhat similar to East Africa, with elephant, lion, leopard, Nile buffalo, roan antelope, tiang, white-eared kob, beisa oryx, eland, lesser kudu, greater kudu, black rhino and other lesser game. On the west bank of the Nile, fauna is more related to the game animals of Central and Western Africa, with such species as forest elephant, Northern white rhino, lion, leopard, forest buffalo, giant eland, bongo, yellow-backed duiker, Nile lechwe, giant forest hog, sitatunga, hartebeest and a variety of duikers. In the northern desert part of Darfur Province, such exotic animals as scimitar oryx, addax, dama gazelle and dorcas gazelle may still be found, but are protected.

While on safari in the early 1970s, on the west bank of the Nile, I encountered a large herd of approximately 20 Northern white rhinos. Since then, the poaching of this species has become rampant, not only in Sudan, but in other parts of Central Africa. This species is now threatened with extinction. The arid Red Sea Hills are the home of the Hadendowa Tribesmen, sometimes called the “fuzzy wuzzies” and has such species as the Nubian ibex, Barbary sheep, Soemmerring’s gazelle, dorcas gazelle, Eritrean gazelle, Salt’s dik dik and an occasional leopard. Not all of the animals are readily available to sport hunters because of their scarcity and conservation efforts. Local safari outfitters are currently trying to offer safaris in the Red Sea Hills.

The reputation of Southern Sudan as a game-rich safari destination spread to other parts of Africa. Soon there began an influx of foreign hunters. Recognizing the potential of an organized safari operation, the Kaikati family from Khartoum in conjunction with partner Angelo Dacey established Nile Safari operations in 1973 in Juba, with John Kaikati as managing director. Nile Safaris went to great expense to provide the best available equipment, vehicles and aircraft to become the premier safari operator in Sudan. The professional hunting staff included local professional hunters Angelo Dacey, Spiros Axarlis, Dimitri Axarlis and George Zafaiou. Soon other safari operations began to emerge. Sudan Safaris, owned and operated by Avo Margossian; Robin Hurt Safaris; Reggie Destro Safaris; and Joe Simoes Safaris were among the notables. Robin Hurt ultimately joined Nile safaris. Other notable professional hunters who migrated to Sudan included East African professional hunters George Angelides, Rolph and Ricky Trappe, Chris Lyon, Tony Moore and Bob Brown. European professional hunters included Franz Coupe, Werner Brach and Rene Ruchaud, as well as others.

In the following years, incessant commercial poaching of elephant and bush meat, coupled with international and tribal warfare began taking a toll on wild game in Sudan. On two different occasions, I personally encountered acts of poaching. While hunting elephants near the Zaire border, I accidentally crossed into Zaire and encountered the carcasses of four elephants which had numerous bullet holes in their bodies from automatic small-arms weapons fire. I quickly retreated back across the border. My friend Spiros Axarlis and I had been hunting elephants along the northern area adjacent to the Bussari River. After tracking the elephants for several miles, we heard automatic small-arms fire about a mile ahead. We concluded that the poachers had encountered the herd of elephants we were tracking and were annihilating them. We made a hasty retreat for our safety.

Over the last many years, there has been both international and local strife in Southern Sudan. The conflict that preceded the creation of the nation of South Sudan introduced weapons of war that were detrimental to the existing game population. Today, there is no organized commercial safari activity in South Sudan and very limited hunting in the Red Sea Hills. The status of the wildlife in these areas remains questionable. I have been very fortunate to enjoy the greatest safari period in Sudan, which is now a hunter’s paradise lost.

Chuck Bazzy of Michigan has hunted most of the countries in Asia, Europe, the South Pacific and South America. He is the author of “Sun Over A Dark Continent” and “Hunting From The Bottom To The Top Of The World” and was the first recipient of SCI’s Lifetime Achievement Award.