Africa’s Most Difficult Quest?

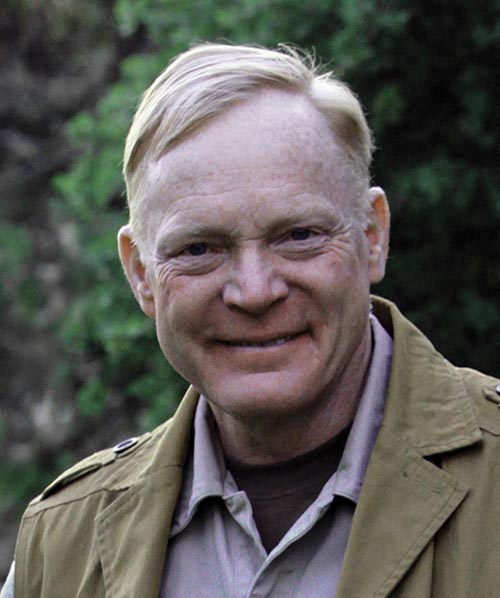

By Craig Boddington

Last morning, last chance. I was with the trackers on a little hill. Hunter Ron Bird and PH Michel Mantheakis were in their blind, somewhere in the dark valley below us, Andy McDonald with them on the camera. We’d been hunting hard for 21 days in Rungwa, central Tanzania. This was the last chance, the last hope. It was not my hunt but an SCI auction hunt that I’d agreed to join. But I wanted success as much as any of us. Now the chances were slim. All I could do was hope as the darkness faded. At the start, we’d seen a lot of male lions. In fact, fully a dozen up to the halfway point. Almost all had been too young and had not reached the six-year-old minimum. By face and body, one lion had been old enough, but his mane was short and scruffy. Not the kind of lion Ron was looking for. Brave, bold and correct, but very risky decision.

Tanzania was the first country to institute a 6-year minimum for a legal lion. It is now standard in most areas that still hunt lions. With habitat shrinking and population dropping, hunting a mature lion has long been a difficult and uncertain quest. The 6-year-rule has not made it easier.

This, of course, is the essence of selective hunting, which is conservation. But aging lions is difficult. A young lion is easy. The rare old-timer, eight or nine, also easy. In their middle years, it’s tough. In that first half, we saw a gorgeous, well-maned lion, possibly six. “Possibly” isn’t good enough, so we passed. Early in the hunt, we’d been covered up with lions. Then we hit a dry spell, a full week with no new lions. With the end approaching, tracks and trail camera showed us the lion we sought, well past maturity, full mane, hunting alone. But this was a clever old boy. On the next-to-last day, he switched baits, moving several miles. We built a new blind, made fly camp that night and were interrupted in the wee hours by a horde of army ants.

Now, on the 21st and final morning, I watched definition come slowly to the dark trees. Then I heard the shot. On that last morning Ron Bird took a magnificent old lion, a true photo finish to a writer’s dream safari.

Not all lion safaris end that way. Last July I joined son-in-law Brad Jannenga on his lion safari in Zambia, hunting the famous Chikwa block in Luangwa North. Booked with Jeff Rann, Brad’s excellent young PH was Davon Goldstone. On the fourth night, two big males hit one of our hippo baits. Nearly identical, both clearly old enough. They feasted most of the night and, with plenty of smelly meat left, they would be back. We built a machan, thinking they might come in before dark, but we expected to catch them lounging around the bait at dawn.

About 9 o’clock, we heard heavy footfalls in dry leaves behind us. At least one of the lions stopped directly underneath us, growled once and then footfalls receded. We never again saw their tracks for the rest of the three-week safari.

As days progressed, Davon kicked himself pretty hard, for no reason. This was not normal lion behavior. Obviously, they smelled us, but lions are usually confident at night. We can only guess that these lions had bad experiences with humans. So, the safari continued.

Lion hunting is not physically demanding, but it’s tough. An odoriferous process of hanging baits, dragging offal, covering miles, widening the net as days pass. We had lionesses on several baits, but the males stayed away. We hunted buffalo and hippo, some plains game as encountered and Brad took a tuskless elephant bull with a brilliant frontal brain shot.

Almost every lion bait had leopards feeding, so we took our time and when an extra-good leopard showed up, we quickly built a blind. Brad had the shortest leopard hunt in my African experience, but the lion situation wasn’t looking good. That can change overnight on any hunt.

On the 18th morning, we approached a bait and saw a tawny form slipping off into the bush. There were mane hairs on the meat, but short. Not good. Trail cam photos also weren’t definitive. We expected the worst, but we had to look at him. It was still sunny and hot when he came in. Nice lion, bright ginger mane. He put on quite a show as he tore at the bait, but Davon had prepared us for disappointment. This lion was max 4 years old and all the wishing in the world wouldn’t make him legal.

The long process of checking baits and dragging continued to the end, but at that point, we knew we were beaten.

Six years old is a conservation and management imperative. Today’s lion safari is a costly, lengthy and difficult undertaking. It’s especially heartbreaking when it comes down to a beautiful lion that just isn’t old enough. Tough pill to swallow, but there are no guarantees. Older males are a small part of any animal population. It’s more difficult with lions. Because of the difficulty in precisely aging — and the penalties for errors — most PHs today are conservative. If they err, it must be on the side of caution. They aren’t really looking for 6-year-old lions. They’re looking for the no-brainer old lion, an even smaller part of the population.

The science can be debated. Two or three males, often brothers, form hunting coalitions. It can be argued that removing one does little harm. However, because of fierce competition, a wild lion usually can’t hold a pride until he’s 5 or 6. His time to breed is short; in just two or three years he will be ushered into retirement by a younger, stronger male. Taking a younger lion means that he has had little time to pass along his genes. In the old days, we had no issues with taking a pride male, on the theory that he would quickly be replaced. True enough, but we weren’t aware that a new male will often kill cubs. Today most ethical PHs avoid pride males. This has become custom, but rarely law, because it’s impossible to know if a lone male is truly solitary, or is simply on walkabout.

Lion family dynamics are fluid, at least for the males. In the course of that Zambian safari, we had three groups of females feeding but no males present. There were cubs, so one assumes they were sired by absent males. Regardless of the absolute science, it’s essential that modern lion hunting take the moral high ground, conservative in harvest, cautious to a fault in aging and avoiding known pride males. All this is critical, because I cannot imagine an Africa where lion hunting is no longer possible.

It is true that Africa’s lion population has plummeted in the last few decades. Sport hunting is not the cause. Primary problems are loss of habitat and competition with agriculture and livestock. There are vast areas where few or no wild lions still exist, but much lion country remains, where a sustainable harvest is not only practical, but is a key tool in maintaining viable populations. To an anti-hunter that’s anathema and a contradiction in terms to most non-hunters. That’s because we don’t live with wild lions. Rural Africans do. They don’t regard the great cats or pachyderms as natural treasures, but as dangerous nuisances. When lions kill their livestock or threaten their children, they deal with the problem, often with poison.

Lions, however, are valuable, more valuable today than ever before. Managed and sustainable hunting places direct value on that dangerous nuisance and reduces human-animal conflict. Protected parks play an important role, and certainly lions in parks have value. However, rural Africans don’t raise crops or livestock in parks, so there is artificiality, and wouldn’t it be sad if lions only existed in pristine parks?

Lions cannot exist in a bubble and are naturally prolific. It’s thus a fact of African wildlife management that lions spill out along the boundaries of all her great parks. In hunting countries, they can be managed with value. In countries that do not have legal sport hunting, they are managed, whether anyone wishes to talk about it or not.

MODERN LION SAFARIS

The world was different when I started hunting in Africa. Three-week “general bag” safaris were the norm, with several of the Big Five on license, usually a lion. Sometimes you got one, but the lion wasn’t a big deal (unless you really wanted one). Times have changed! Today, hunting a lion is one of the most specialized hunts on the African continent and one of the least successful. Also, one of the most expensive. I regret this, and I’m especially concerned for younger hunters coming up who dream of someday hunting a lion.

The African lion is extinct, endangered, or threatened in much former range but mostly stable where hunted and overpopulated in some areas. He is one of the world’s great game animals, and still very much huntable. In our supply-and-demand world, it is not unusual for hunts for high-profile species with limited opportunity to carry high prices.

In North America, Alaskan brown bears and Stone sheep have skyrocketed. Elsewhere, we might compare a lion safari with an Altai argali or a markhor. The supply of good areas offering reasonable opportunity for a big 6-year-old lion has diminished. As part of collective strategy for keeping lion hunting open, quotas are down.

In Zambia not so long ago, a quota of three lions per hunting block was common. Considered too many, for seven years the quota has been one lion per block, so Brad was after the one Chikwa lion. In Zambia, that’s a potential country-wide harvest in the low 20s, sustainable, and increasing the value and importance of each lion harvested.

Tanzania, with the largest lion population, has a similarly reduced quota but holds Africa’s largest population and greatest opportunity. Botswana President Mokgweetsi Masisi was singularly responsible for reopening hunting. He has stated that all species legally on license will be hunted, which includes lion. At this writing, no lion quotas have been allocated, but after years of no lion hunting, Botswana should be awesome.

Zimbabwe has excellent lion hunting. In the northwest Matetsi blocks, in the west along the Hwange Park, and on the big conservancies in the south. In the Zambezi Valley, lions are overpopulated, and have wreaked havoc on buffalo and other prey species.

Mozambique has good lion hunting in the north and around the huge Nyasa Reserve, successful hunting with a conservative quota. She also has a large lion population in and around the central Gorongosa National Park, and a huge boundary with Kruger in the south. We all know about the introduction of lions into the Marromeu complex near the Zambezi delta, initially 24, already into the 80s. These lions are not currently hunted, but eventually must be.

Arid Namibia has limited lion habitat, but there is some hunting in the far north. Conservative quotas are in place in Caprivi, but few permits are being issued. When and where a Namibian lion permit can be obtained, quality and opportunity are outstanding. Her huge Etosha National Park, and Kalahari Gemsbok National Park to the southeast, are massive reservoirs of dense lion populations.

My own last lion, a wonderful old warrior, was taken on a “problem lion permit” on the Etosha boundary. There is no established quota for lion hunting along Etosha, but dozens of lions are taken annually by Namibian farmers for livestock predation with no value added.

There is another uncomfortable subject in modern lion hunting: trophy importation. Despite what we hear, few nations have stopped importation of lions. However, some have more stringent requirements (including the EU and USA). Undoubtedly well-intentioned, prohibiting importation of legally sport-hunted lion trophy parts is bad, because it does nothing for the lions. Quite the reverse, value is reduced and lions without value are once again dangerous nuisances. At this writing, legally sport-hunted lions are importable into the United States, but not from all areas where lions are huntable. Range state authorities and operators are required to meet “enhancement findings,” demonstrating that hunting is sustainable and beneficial to the lions. Hunters applying to USFWS for import permits are required to include enhancement supporting information on their applications.

This is just one of many behind-the-scenes battles that SCI and other conservation organizations fight on a daily basis. SCI works directly with African range states and USFWS, primarily through the African Wildlife Consultative Forum (AWCF). Sport-hunted lions are entering the United States, but it depends on where taken. Make no assumptions, but wild lions are importable with enhancement findings. USFWS is not currently issuing import permits for captive-bred lions.

PERSISTENCE PAYS

Before my time, when most safaris took place in British East Africa, lions were considered vermin, no license, no limit, to make way for cow and plow. Unthinkable today, multiples were common. Hemingway shot three on his 1933 safari. Ruark shot two in 1952, and my uncle, Art Popham, shot two in 1956. That’s the way it was done, but lions dwindled before we were aware.

A lion is what I craved on my first safari, in Kenya, 1977. I failed and it was crushing blow. I turned down two young males, good on me, but in those days, we didn’t think about age or pride status, they just weren’t the lions I’d dreamed of. I didn’t know that good lions were getting scarce. Over the next few years, I would figure it out. I was 105 hunting days to my first lion, Zambia in 1983. Not so good on me, I shot a last-day lion that I’m ashamed of. Legal and acceptable then, not today.

I’m on board with today’s ultra-selectivity, because it’s good for the lions and good for lion hunting. But that’s easy for me to say, right? I would go on to take other lions. Before it became as difficult as today. So, while I could feel for son-in-law Brad while the days ran out on his first lion safari, I couldn’t put myself in his place. Today’s lion safari is costlier than in my day, more difficult, more selective. I cannot offer a success percentage. It depends on where you hunt, who you hunt with and your own luck. Reality, not every modern lion safari will succeed, and because of health, finances and God knows what, not every lion hunter can try again.

Brad got a rare second chance. With permits still in place, Jeff Rann worked it out for him to try again. Davon Goldstone was getting married (for God’s sake), rushed from his bride and met Brad back in Chikwa just two months later. It started as a repeat of our July safari, two big males feeding, not the same two, but these were bigger and older! Hit and gone. It finished as a repeat of Ron Bird’s Tanzanian hunt a decade earlier, with these lions switching baits. It takes a smart lion hunter to figure this stuff out. Ron Bird had an old pro in Michel Mantheakis, and Brad had a savvy young pro in Davon Goldstone.

The lion they shot, on a lovely afternoon on the bank of the Luangwa River, is the finest wild lion I’ve personally seen. Worth every cent and worth every second of effort for 29 tough days.

For those good at math, that’s 79 days less than it took me for my first lion, which was definitely not such a lion!