Hunt Doctors – What To Pack In A Survival Kit

Your survival kit is for emergencies — unexpected occurrences where, for some reason, you find yourself facing a direr situation than planned. Global Rescue expert Harding Bush explains what to pack in a survival kit.

Any time you take yourself into the wilderness, you are entering some level of a survival situation. There are many emergencies and contingencies in the backcountry that do not have a medical requirement. For these instances, you need survival equipment.

Some survival equipment includes things you use routinely throughout your time in the remote locations, and some are specific to an emergency. All safety and survival needs fall into one or more of the following categories: communications, first aid, food and water, shelter, fire and navigation.

These six categories remain consistent, however the importance of each changes with geographic location and the duration of your planned trip. If you are doing a multi-day winter hike over the Presidential range in New Hampshire’s White Mountains, shelter takes priority over water. Water would take precedence in an overland desert crossing in Australia or Africa.

Here are some ideas to consider when building a survival kit.

ONE: Don’t overdo it.

If you need to take so much survival gear it overwhelms your pack, choose another activity; you are not going to enjoy yourself. More likely, you are not realistic about the risks and your capabilities.If you are not an experienced trapper, don’t plan on trapping an animal for food. The same with fishing line, hooks and lures. You are better off bringing bouillon cubes and energy bars in a survival kit.

If you have a sleeping bag, bivvy bag, ground pad and tent, you don’t need a large tarp for survival. A space blanket will be sufficient. The larger, more durable, waterproof space blankets reflective on one side and bright on the other (signaling) are ideal for survival consideration in colder temps.

TWO: Protect your equipment.

All electronics, phones, GPS and satellite messaging devices should be protected from the elements and potential impact. Waterproof containers or cases should be considered. Just because a manufacturer says an item is guaranteed to be waterproof does not mean it necessarily is — a guarantee means nothing out in the wilderness. Quality zip lock bags are practical waterproofing, especially if they are doubled up and you are not in a maritime environment.

Understand that much of your equipment, depending on the environment, is life support equipment. This includes water bottles, an aluminum cup for boiling water, a sleeping bag and ground pad, and clothing items such as hats, mittens and even sunglasses.

Water bottles should be in a secured backpack pouch, not placed where it can fall out without you knowing.Water purifying pumps are prone to breakage if they are not well protected. Chemical options, such as chlorine or iodine tablets, should be in the survival kit for this reason.

THREE: Know your gear.

Be familiar with all your equipment and practice using it before leaving for the backcountry. If you have a spring-loaded ferro rod fire starter in your survival kit, make sure you know how it works and you have practiced with it at home. If you have iodine or chlorine tablets for purifying water in your survival kit, learn how to use them.

FOUR: Electronics will fail.

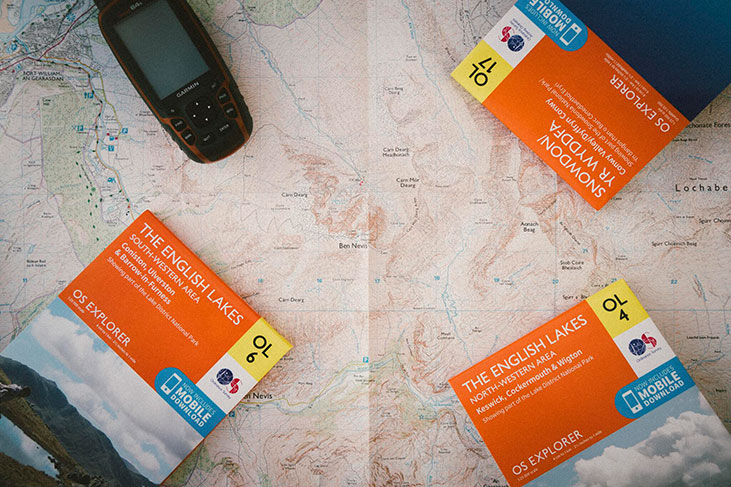

Have a back-up plan for anything electronic related. Even if you are navigating on your phone or GPS, you must also have — and know how to use — a map and compass. Phones lose service, GPSs lose connections in thick forests and steep terrain, batteries die and machines break.

Have extra batteries or charging capability for all electronic devices. A communications plan needs to include non-electronic back-up, such as leaving a trip plan with a responsible person. You should also bring non-electronic emergency signaling devices such as a whistle, strobe light, signal mirror or other ground-to-air signals, such as a bright colored space blanket, parka or sleeping bag.

Understand how to use your mobile or satellite phone. Make sure you have a written copy of all important numbers, laminate these numbers and put them in your rainproof notebook. It’s handy to have a small notebook to write down instructions from a rescue service or write down critical information, such as your geographic coordinates, before making an emergency call. Bring a few pencils, not pens because pens break and ink freezes.

FIVE: Pack items with more than one purpose.

Why would you ever carry a knife with a single blade when you can bring a knife with multiple blades and multiple uses? Swiss Army knives or multi-tools, for example, are a much better option. These multi-feature knives have knife blades for cutting cord to make a shelter, a saw to cut kindling wood, can openers, tweezers and scissors (which help with first aid), screwdrivers and pliers (to repair or maintain equipment).

The uses for zip ties, paracord and duct tape are endless. With these items, you can fix nearly anything long enough to get out of the field safely. Wrap 20 feet of duct tape around a Nalgene bottle, dog-ear the end tape so you can peel it off without removing your gloves. It is even better if the tape is bright orange — you now have a water bottle that is part water bottle, part signaling device, repair kit and first-aid kit.

SIX: Always be prepared for the night.

Always carry a quality headlamp and extra batteries. Headlamps are critical because they leave your hands free to cut kindling wood, conduct first aid and boil water in the dark.

There are numerous small stoves, either liquid fuel or gas canister, you should always carry while in the backcountry. However, these stoves are useless if you don’t have a metal or aluminum cup.

Always have the ability to make fire. This includes a windproof lighter in your pocket, a mechanical fire-starting device in your pack, and waterproof matches in a waterproof container in your survival kit. Small tea candles are a good idea; they can provide light, and they will save many matches.

Something warm to eat or drink is essential in colder environments; having a stove, fuel and small pot to boil water in is critical. A warm meal or drink can make a cold night seem a lot shorter.

SEVEN: Where do I carry my survival kit?

There are survival items you will use throughout your time in the backcountry, like your water bottle and clothing.

Other items take on more of a life support role, depending on the weather or environment. Contingency items can be safely tucked away, ready for use when necessary. Here’s a few survival kit items that can be packed away in a small pelican case for contingency use:

- Waterproof matches

- A small compass

- A small sewing kit

- 50 feet of paracord

- 20 feet of duct tape

- Extra batteries for everything

- Water purification tablets

- Small candles

- Space blanket

- Signal mirror, whistle or emergency flares

- Bouillon cubes or energy bars

- Some cash

Do not split up survival gear. You may find yourself alone. Everyone should have their own first aid kit and critical survival gear. Everyone should have a portable stove, fuel and pot in colder environments for the same reason.

EIGHT: Learn and practice survival skills in a safe environment.

While effective learning takes place after making mistakes in the backcountry, it is not a good idea to head into the backcountry with just your survival gear with the intent of learning to use it. Practice survival skills in a safe and supervised environment and be thoroughly comfortable using them before your trip.

Safari Club International highly recommends purchasing a Global Rescue membership prior to your next trip. Single trip, annual and family options are available. Click here for more information or call (617) 459-4200 and mention you’re a Safari Club International member.

Harding Bush is the associate manager of operations at Global Rescue, the pioneer of worldwide field rescue. He is a 20-year special operations forces veteran with an additional 10 years of experience in international travel and corporate security. He was also the senior survival instructor at the US Navy Survival, Evasion, Resistance and Escape (SERE) Course in Rangeley, Maine.