Bullets Are More Than Just Projectiles

I guess I’m just showing my age, but I can remember when a bullet…was a bullet… was a bullet. If you used factory ammo, that meant a Remington Core-Lokt or a Winchester Power Point. Yes, they also offered the Bronze Point and Silvertip, respectively, but I’d bet that 60 percent of the lead sent downrange during hunting seasons were those two bullets.

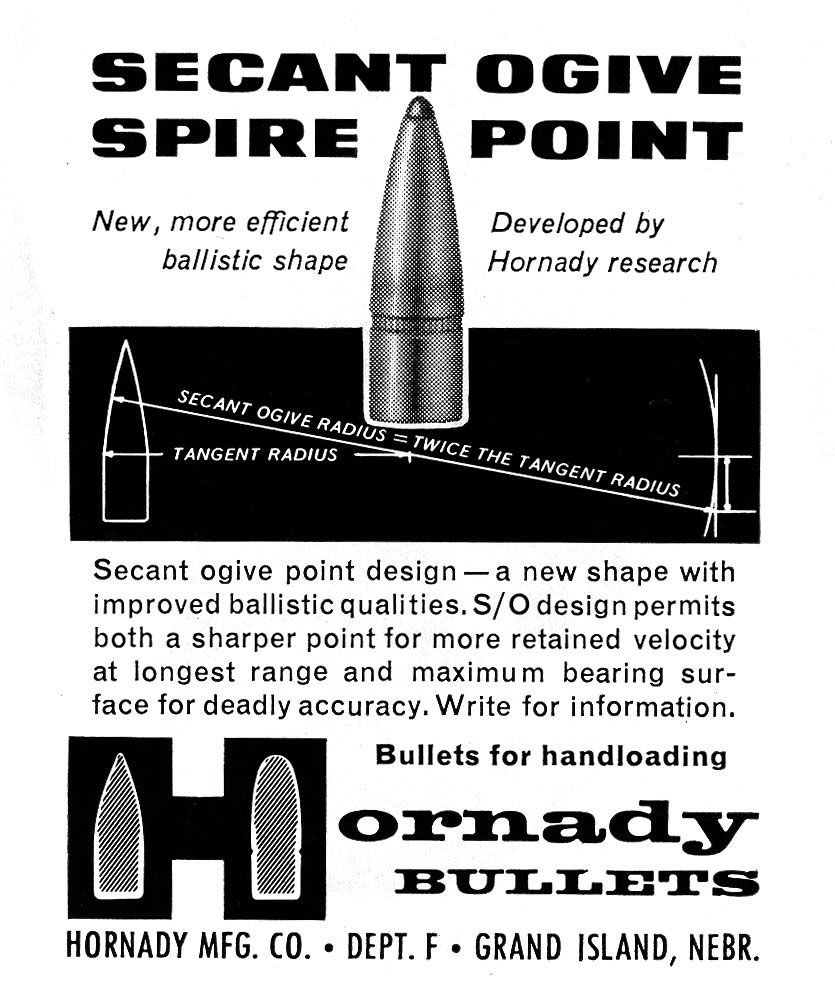

Back then we had no idea just how complicated and technical bullet construction could be. If you were a handloader you had the Nosler Partition, but that was considered pretty exotic by the average handloading deer hunter of the day and the flagship bullets of Hornady, Speer and Sierra weren’t much different from what the Big 2 were offering in their factory ammo, which were simple bullets of cup and draw construction.

Back then we had no idea just how complicated and technical bullet construction could be. If you were a handloader you had the Nosler Partition, but that was considered pretty exotic by the average handloading deer hunter of the day and the flagship bullets of Hornady, Speer and Sierra weren’t much different from what the Big 2 were offering in their factory ammo, which were simple bullets of cup and draw construction.

At the risk of oversimplifying, the process consists of punching disks or planchets from sheets of copper/zinc alloy and through successive punch dies a deep, slender cup is formed. Through the open end a piece of lead wire of appropriate diameter is inserted, and through another series of dies the nose, either round or spitzer, is formed, leaving a tiny portion of the lead core exposed at the tip to initiate expansion.

That was by no means the only way to produce a bullet back then, but it was the predominant process because it allowed high volume production and produced acceptably accurate bullets and fairly reliable expansion. Even the most streamlined cup and draw flat-base bullets of the day in the most popular game calibers; .270, 7mm and .30, had G1 Ballistic Coefficients in the low 400s. Pretty darn good, but not so much by today’s standards.

Things began to change in the late `70s when Federal, determined to challenge the supremacy of Remington and Winchester, introduced its Premium line of rifle ammunition. In so doing they did the unthinkable. They began using Nosler and Sierra bullets and advertising the fact, which in effect was a tacit admission that someone other than they could make a worthwhile bullet! That just wasn’t done back then and it took the Big 2 several years before they saw the efficacy of doing the same.

Thus began the “premium ammunition era” which is still going strong. Today virtually every bullet manufacturer is represented in factory ammunition either in their own line or in those of most major manufacturers here and abroad. However, within the past few years the emphasis has really concentrated on the bullets themselves, thanks primarily to the market’s obsession with “long range” — long range rifles, long range ammunition, long range bullets, long range optics. What’s next, long range underwear?

Shooting at distances of 1,000 yards and beyond places challenging requirements on bullet design and construction, in light of the fact that some are designed strictly for target shooting, while others are designed for hunting. And higher velocities and faster twist rates further complicate bullet design.

Take varmint/predator hunting for example. Here we want a highly frangible bullet yet one that has to stay together, something some loads can’t do when fired in fast twist barrels. All the major ammo producers offer a .223 Rem. loading of 35, 38 or 40 grains that churn up some 3,750 to 4,000 fps. If my math is right, in a 1-7” twist you’re looking at 385,000-400,000 rpm’s!

Take varmint/predator hunting for example. Here we want a highly frangible bullet yet one that has to stay together, something some loads can’t do when fired in fast twist barrels. All the major ammo producers offer a .223 Rem. loading of 35, 38 or 40 grains that churn up some 3,750 to 4,000 fps. If my math is right, in a 1-7” twist you’re looking at 385,000-400,000 rpm’s!

So, we have to have a frangible bullet, yet one that has to stay together when incredible centrifugal forces wants to tear it apart. Now we all know that the fast 1-7 and 1-8 twist rates are for stabilizing heavy .224 bullets of up to 88 grains, but the siren call of hyper velocity is a song that many succumb to. On my last two prairie rat shoots we had bullets blowing up in little puffs of white smoke about 25 yards from the muzzle when fired through ARs and fast twist .223s.

In designing game bullets there’s a bit more of a challenge than with match bullets because the latter’s only job in competition is to be as accurate and as streamlined as possible and when it gets to its destination all it has to do is punch a hole in the paper. No expansion necessary. With game bullets we also want high BC’s and accuracy, but they must also have the controlled expansion necessary for humane lethality on live game. That’s a challenge that will never be solved completely, but we are making progress.

The reason it will never be completely solved is because a bullet can be designed to expand optimally only over a certain range of velocity. I’m sure we’ve all seen ammo ads showing a side-by-side lineup of a given bullet recovered from water or ballistic gelatin at ranges from 50 to 500 or more yards. The 50-yard bullet shows expansion of at least two times the diameter of the base of the bullet, whereas the bullet recovered from the longest distance shows little more than initial expansion of the nose and measures even less than base diameter. And do keep in mind that those bullets were recovered from a homogeneous medium. When a bullet strikes a rib or shoulder blade, it’s a whole `nother ball game.

With today’s new generation of game bullets the ranges at which we can rely on optimal terminal performance is broader than ever, but until we have self-propelled bullets that maintain a constant velocity from Point A to Point B, it’s always going to be a compromise to one degree or another. Unfortunately, there are a lot of long-range shooters who develop loads, practice and compete using match bullets, but who are also hunters and despite admonitions to the contrary, for confidence sake use those same loads for hunting.

Again, as a perfect example of that siren call I talked about, Hornady’s new .300 PRC cartridge pushes a 225-grain ELD Match bullet that has a G1 BC of .777! Compared to today’s ultra magnum .30s this bullet starts out at a relatively modest 2,810 fps, but at 500 yards it’s still traveling at 2,250 fps and packing 2,528 ft./lbs. of energy. That’s 559 fps faster and 1,176 ft. lbs. more energy than Hornady’s 180-grain Interlock .30-06 loading!

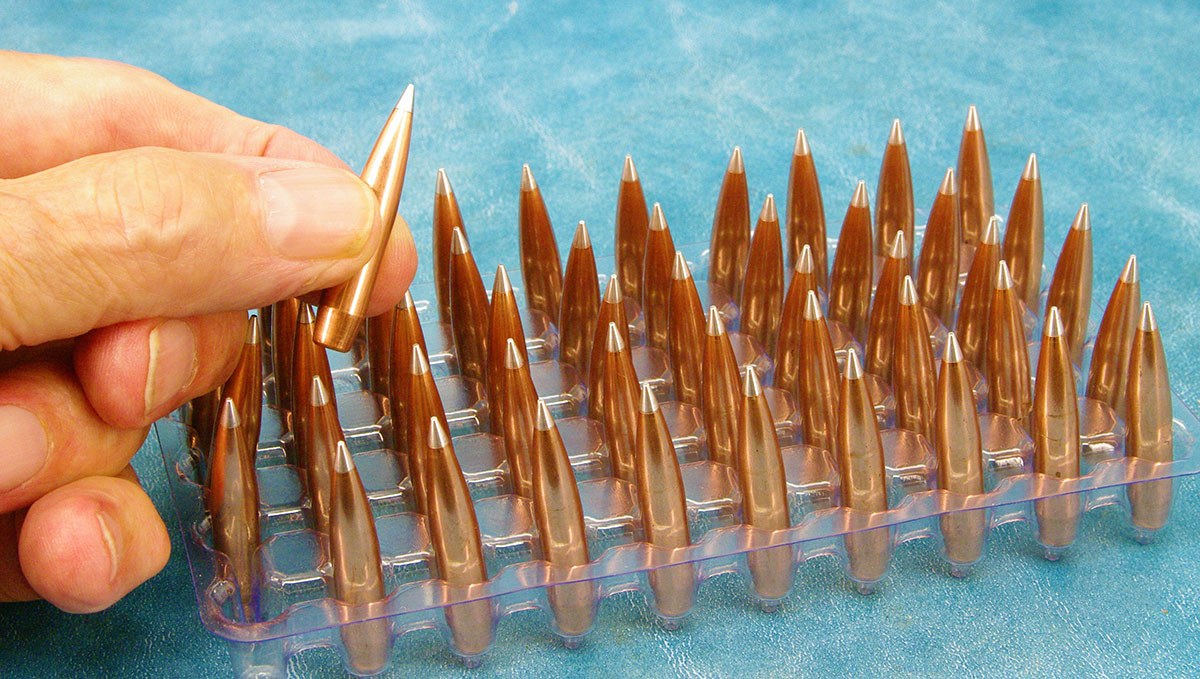

Remember when the heaviest .30 caliber factory game load was a 220-grain bullet? Forget that. Hornady’s new A-Tip aluminum-tipped match bullets, which at this time are sold only as components and not available in Hornady ammo, are offered in two weights: 230 and 250 grains, boasting G1 BC’s of .823 and .878 respectively! Berger is another bullet maker who started out making VLD match bullets and now offers a full line of hunting bullets with similar Ballistic Coefficients. Barnes started making game bullets and now offers a comprehensive line of match projectiles, which again are just as aerodynamically efficient or more so.

I’ve seen many tacit endorsements for using match bullets on game simply because that particular individual had success doing so. But those who’ve had to go on long and arduous tracking jobs trying to recover a wounded animal, or worse – an animal that was obviously hit and never recovered, are reluctant to admit such things.

Don’t get me wrong, many clean kills are made using match bullets and some makers claim theirs will excel at either task, but the odds are still with those who use game bullets for game and match bullets for recreational and competitive long range shooting.–Jon R. Sundra