Armchair Safari – The African Buffalo by F. Jackson

The Badminton Library, whose volumes were printed in 1894, was one of the first anthologies on big game hunting. The African Cape buffalo section was authored by well known East Africa resident, hunter and government officer, F. Jackson. The following account of a buffalo hunt he once had in the Arusha-wa-chini district in March 1887 will serve as an illustration of the buffalo’s cunning, ferocity and vitality.

The Badminton Library, whose volumes were printed in 1894, was one of the first anthologies on big game hunting. The African Cape buffalo section was authored by well known East Africa resident, hunter and government officer, F. Jackson. The following account of a buffalo hunt he once had in the Arusha-wa-chini district in March 1887 will serve as an illustration of the buffalo’s cunning, ferocity and vitality.

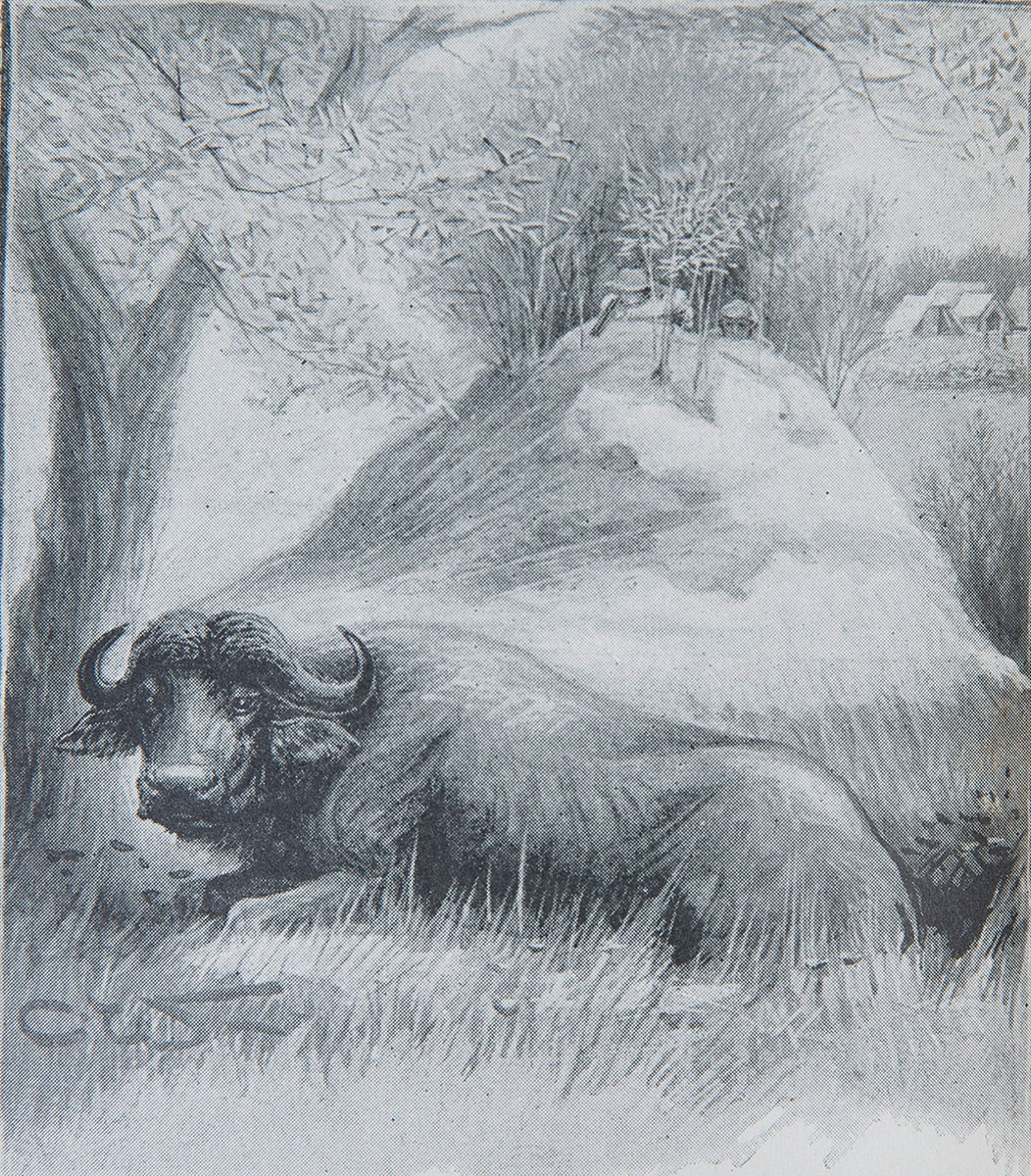

I was encamped on the river Weri-weri, a short distance above the native villages, but as the people were afraid to prowl far from their homes on account of the Masai and other enemies, game was not only very plentiful but also less wild than elsewhere. Buffaloes were very numerous, in large herds and with a good many old bulls either solitary or in small bands of two and three. This country was one of the best I was ever in from a stalker’s view, as the alluvial plains on both banks of the river, though open, were dotted about with trees of various kinds and sizes, and in places were quite park-like in appearance. There were also numerous ant heaps, and occasionally small bushes dotted about, besides the grass which was about 18 inches high. All of this afforded capital cover.

The plain on the left or eastern bank of the river varied from a mile to a mile and a half in width and was bordered on its eastern side by a belt of thick bush and clumps of forest trees. In these the buffalo took up their quarters during the heat of the day, coming out again in the evening to feed in the open during the night and early morning. The bush, like most African bush which borders on open plain, was fairly thin on the outskirts and was what is commonly known as open bush. Here was a very favorite feeding ground for waterbuck, impala and other bush loving antelopes, besides buffaloes, which were generally found feeding in the early morning before the sun became too hot.

As I walked over the plain on the left bank of the river I passed great quantities of game, including eland, waterbuck, impala, and a troop of 13 ostriches which I tried many times to circumvent, but always unsuccessfully until I drove them, when I got a fine old cock bird. In addition there were zebra and hartebeest. After going about three miles up the river, I at last saw two old bull buffaloes on the opposite side of the plain, quietly feeding close to an isolated patch of bush which stood some distance from the main belt out in the plain. As buffaloes have rather poor sight and as there were two or three big trees between the beasts and myself, about 400 yards from them, I told my men, some 25 in number, to follow me in single file and we all got up to a tree without the least trouble.

At that moment, a herd of zebras, which had hitherto taken no notice of us, suddenly took fright on getting our wind, and galloped round between us and the buffaloes. The latter, being thus disturbed, lumbered off into the isolated patch of thick bush close by. After giving them time to settle down and forget their fears, I proceeded more cautiously, with only my two gun bearers, leaving the rest of my men under the tree with orders to come only when they heard a shot or other signal. However the buffaloes were evidently on the alert and as they were standing in the shade, they discovered us when we were still 100 yards off and as we crossed the great open plain. They bolted out on the opposite side, making for the main bush. Running round the clump to try and keep them in sight, I was just in time to see them enter the open bush and disappear from view.

At that moment, a herd of zebras, which had hitherto taken no notice of us, suddenly took fright on getting our wind, and galloped round between us and the buffaloes. The latter, being thus disturbed, lumbered off into the isolated patch of thick bush close by. After giving them time to settle down and forget their fears, I proceeded more cautiously, with only my two gun bearers, leaving the rest of my men under the tree with orders to come only when they heard a shot or other signal. However the buffaloes were evidently on the alert and as they were standing in the shade, they discovered us when we were still 100 yards off and as we crossed the great open plain. They bolted out on the opposite side, making for the main bush. Running round the clump to try and keep them in sight, I was just in time to see them enter the open bush and disappear from view.

This made it necessary for us to take up their spoor and while the gun bearers were so engaged, I kept a lookout ahead. After going a short distance I suddenly saw one of the bulls trotting back towards us, and when about 100 yards off it dived into a small dense clump of bush some 20 yards square. It was followed almost immediately by the other bull. I have read about these processions, though it was the first and only instance in my own experience. My suspicions were aroused. So instead of making straight for them along their spoor, I made a detour through the straggling bush and stalked up to a small tree within 60 yards of the clump they were in. At first I could see nothing of them, the clump being too thick, but with the aid of binoculars, I made out the head and outline of the neck of one bull as it stood broadside.

Taking the 8-bore I fired at the place where I thought his shoulder ought to be, and he fell with a deep groan. This at first made me believe that he was either dead or dying. The other bull promptly floundered out of the bush and stood broadside, looking on in my direction sufficiently long enough to enable me to change rifles and plant a 4-bore bullet in his shoulder. But this shot was too high and too far back. Off he went. In the meantime, the other bull in the clump, after kicking and plunging about, picked himself up and went after his companion. As I could see he was very lame, I was so certain he would not go far that I did not fire at him again.

Before following them I took a hasty survey of the ground and found my suspicions confirmed. They had returned on their own spoor when I first saw them trotting back and had I not seen them I should have followed their spoor, which I found led close past the bush they were in. They might then have been able to charge me. I certainly might have been at a disadvantage. I then hurried after them with the 8-bore and, outrunning my gun bearers, soon overtook them. They were both lame. I got to within 70 yards when the one who had received the 4-bore bullet was a trifle behind the other. He evidently heard me coming along behind him, so he whisked around and stood broadside staring at me while the other continued to retreat.

Sitting down (my favorite shooting position) and as I was much blown away after my run with a heavy rifle, I took a steady shot at his shoulder and definitely heard the bullet strike. But it had absolutely no effect. The bull never even flinched! Hastily jamming another cartridge in order to have one in reserve in case he should charge, I again fired at his shoulder and he dropped as if struck by lightning. He fell so quickly that I did not see him fall. He was, however, not dead. I could see his side heaving above the top of the grass as he lay. By this time the gun bearers had come up, followed shortly afterwards by the rest of the men, who had come on when they heard the first two shots.

![]() Seeing that the bull was down they ran up to it like a pack of wolves to cut its throat. But knowing that it was not dead, I ran ahead and warned them not to go near. But they were too excited to pay heed to my warning. They were standing all around the bull. After a desperate effort to regain its legs, the bull jumped up, sending the men flying in all directions. Catching sight of my second gun bearer, who had also gone up to it, and who at the time was carrying my 4-bore, it went straight for him. The man bolted, but finding that the bull was close upon him, dropped the rifles and the stock was snapped short off at the grip by the buffalo treading on it. The man continued to run for dear life with the buffalo being close and giving a furious grunt with each step.

Seeing that the bull was down they ran up to it like a pack of wolves to cut its throat. But knowing that it was not dead, I ran ahead and warned them not to go near. But they were too excited to pay heed to my warning. They were standing all around the bull. After a desperate effort to regain its legs, the bull jumped up, sending the men flying in all directions. Catching sight of my second gun bearer, who had also gone up to it, and who at the time was carrying my 4-bore, it went straight for him. The man bolted, but finding that the bull was close upon him, dropped the rifles and the stock was snapped short off at the grip by the buffalo treading on it. The man continued to run for dear life with the buffalo being close and giving a furious grunt with each step.

For some time, I was unable to shoot as the rest of the men were scattered and dodging about between myself and the buffalo. So I shouted to the gun bearer to run towards me, which he did and I was able to fire, but the 8-bore bullet had apparently no effect on the infuriated beast. At the same moment the man doubled and ran straight away from me, making for a small tree about 100 yards off, twisting and turning as he ran. But the buffalo still stuck close to him and doubled as quickly as the man did. All this time I was tearing along in pursuit, hoping to get a shot but dared not fire for fear of hitting the man, who was dodging about from side to side. I was some 60 yards behind when they reached the tree.

This the man endeavored to catch hold of so as to swing himself around, but he was going so fast that the impetus caused his hand to slip and he fell forward flat on his face into the grass, which was some two and half feet high under the shade tree. The buffalo, being so close to him at the time, over-shot him and the tree. But the bull whipped around twice, I saw it give a vicious dig at the man with its head and then kneel down two or three times. I could only see its stern above the grass. By the time I got close enough the buffalo was in a kneeling position and thinking the man was probably dead, I raised my rifle to fire. Suddenly the man, whom I could not see in the longish grass, raised his head and shoulders from underneath the beast’s stomach, directly in the line of fire.

I had to pause until he wriggled himself out of line. Finally a couple of bullets at close quarters settled this cunning, savage, yet plucky best. The man’s back and the calves of his legs were covered with blood from the buffalo’s mouth and nostrils during the run, showing how very close it had been to him all the time. He told me afterwards that when he turned over on to his back, the buffalo made a bad shot each time it lunged at him with its head, or tried to kneel on him, owing perhaps to the fact that it was weak and dazed from the loss of blood. The man was therefore able to twist himself out of the way. It, however caught him and delivered a severe blow to the man’s knee, which nearly dislocated it. This made it necessary to carry the man back to camp. After a little careful doctoring and some rest the man was able to take to the field again in three weeks.

On cutting up the bull, I found the 4-bore bullet was too far back and also too high. The first 8-bore bullet had struck far behind the shoulder and had gone through both lungs rather low down. In retrospect I think that if the bull had been left alone after it had been knocked down by the second shot, it would soon have died quietly. But with the men rushing up to it and standing around, it seemed to inspire the bull with a final desire for revenge. The second 8-bore bullet was, as I expected, too high and passed through the dorsal ridge just above the vertebrae. The shot fired as it ran past me caught it in the proper place, went through both lungs and just grazed the heart. It is likely that this was the shot which prevented what might have been a serious accident.

On cutting up the bull, I found the 4-bore bullet was too far back and also too high. The first 8-bore bullet had struck far behind the shoulder and had gone through both lungs rather low down. In retrospect I think that if the bull had been left alone after it had been knocked down by the second shot, it would soon have died quietly. But with the men rushing up to it and standing around, it seemed to inspire the bull with a final desire for revenge. The second 8-bore bullet was, as I expected, too high and passed through the dorsal ridge just above the vertebrae. The shot fired as it ran past me caught it in the proper place, went through both lungs and just grazed the heart. It is likely that this was the shot which prevented what might have been a serious accident.

The other old bull, although we followed him for a long time, eager for revenge, got clean away.

Shooting buffaloes in thick bush, when the only means of finding them is by tracking, is not only intensely exciting but also dangerous and often unsatisfactory. It is exciting because in thick cover the hunter must make up his mind that there will be little chance of seeing a bull until he is pretty close to it. If the hunter is at all jumpy as he steals carefully along, avoiding sticks and dry crackling leaves and loose stones, or brushing up against the bush, he has ample time to think about and realize the danger he is possibly encountering. The deep guttural grunts of buffalo, as they stand and lie about, which can be heard at long distances in the stillness of the bush, are not calculated to sooth the nerves of even the coolest and most experienced big game hunter. Many have felt their hearts thumping against their ribs to an extent which is not conducive to good shooting. If a herd is scattered about, there is a chance that in a stampede, some of the herd that might not have seen or smelled the hunter could be coming towards him instead of rushing away. In short, buffalo hunting can be dangerous and the chances are that the buffalo can turn vicious. A bull that is aware of its enemy is more likely to charge upon being fired at and wounded. But buffalo hunting is always great sport.–Selected and edited by Ellen Enzler-Herring of Trophy Room Books