Armchair Safari Kumm Hausaland

“As a youth I followed the chase by mere nature and inclination, but now I know I have a right to follow it, because it gives me endurance, promptness, courage self-control as well as health and cheerfulness.” Charles Kingsley

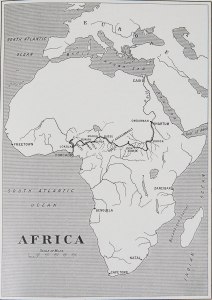

Karl Kumm was a most interesting individual. He traveled on foot from Nigeria to Egypt, not only to explore and hunt, but also to attempt to prevent the spread of Islam through North Africa, which he thought would cause much trouble in years to come. (As long as Islam is what it is, a Mohammedan fanatical outbreak was expected at any time. As these territories are very far removed from Europe, to have coped with such an outbreak would have been exceedingly difficult.) Western Sudan and Timbuctu were known 100 years before Kumm arrived in Africa. The Niger territories and Hausaland were known 1,000 years before he explored. Samuel Baker and George Schweinfurth explored the Upper Nile, but between the Central Sudan, the Lake Chad region and the Nile Valley, some 50,000 square miles had, up to 1870, remained untouched. It was a happy hunting ground both for big game hunters and slave raiders in the center of Africa. Kumm’s was a tough trip, filled with daily adventures and challenges.

Karl Kumm was a most interesting individual. He traveled on foot from Nigeria to Egypt, not only to explore and hunt, but also to attempt to prevent the spread of Islam through North Africa, which he thought would cause much trouble in years to come. (As long as Islam is what it is, a Mohammedan fanatical outbreak was expected at any time. As these territories are very far removed from Europe, to have coped with such an outbreak would have been exceedingly difficult.) Western Sudan and Timbuctu were known 100 years before Kumm arrived in Africa. The Niger territories and Hausaland were known 1,000 years before he explored. Samuel Baker and George Schweinfurth explored the Upper Nile, but between the Central Sudan, the Lake Chad region and the Nile Valley, some 50,000 square miles had, up to 1870, remained untouched. It was a happy hunting ground both for big game hunters and slave raiders in the center of Africa. Kumm’s was a tough trip, filled with daily adventures and challenges.

It was again time to start a new phase of our journey to a place 40 miles distant. There are certain difficulties connected with the daily start in Africa: the weighing and apportioning of the loads, roping of these loads, bandaging of sore feet, cure of digestive troubles — for all these things are carefully saved up by the boys until the last moment. And, when everything is finally settled, one of the boys has “gone off to the village to buy food.” He is diligently trading. That the white man and all the other carriers have to wait, and might, perchance, dislike being kept waiting does not enter his head. The natives are delightfully improvident and irresponsible. They are quite ready to share their last bite of food, and the white man, having secured their trust, they will do anything for him — EXCEPT be punctual.

Finally we made it to the very center of the Sudan. There are representatives of 20 or 30 different tribes and nations in Sudan all around. Before me stretches 1 ,000 miles until I reach Sobat. So the problem of transport is once more before me. The land through which I shall have to pass is unexplored. To take carriers and send them back is impractical. So we shall purchase oxen to carry the loads. I am looking forward to the unknown country ahead, wondering what it will bring. I know there are plenty of people and vast herds of elephants, but this is the only information I have.

Since leaving Fort Archambault, with 30 men, two horses, four rifles, a shotgun and revolver, I looked forward to seeing some of the herds of elephants about which everyone talked. I longed to get sight of them, put my shooting powers to the test, and secure a few pounds worth of ivory. We pitched our tent some distance from a small Kirdi village and retired early. The hunter who had been sent ahead the previous day returned to report that elephants were in the neighborhood. They had been heard by the village people. In spite of their large size, in this area it is easier to hear than to see elephants.

For the next five days, for about six hours each day, we followed elephant tracks from two herds. There was a herd of 60 on the west and one of 40 on the east bank of the Shari River. On the first day all we got was a severe drenching through a heavy tornado. We never got near elephants. By one in the afternoon, the spoor was at least four hours old. With some satisfaction, I killed two hartebeests on our way back to the village so that my tired men had meat to share among them. The hartebeest in the Shari valley is similar to the East African and an entirely different species to that of Northern Nigeria. Its coat is darker, and its horns smaller and somewhat differently shaped. The long head and cow-like gallop is the same.

But the next day would be a red letter day. Starting at 6 a.m. with about 15 natives and myself, we went about three miles up the Shari and crossed the river close to a little fishing village. The ground was very wet after yesterday’s shower. My horse kept slipping and once fell heavily on the sloping ground. Travelling became so bad that I felt like giving up. Yet, I sensed there were elephants nearby. And if it was hard going for us, it must be hard for the elephants. Perhaps they would curtail their morning walk, which might take them over 40 miles of ground.

At 8:30 a.m. we came upon relative fresh spoor, only two hours old. A herd of 40 or 50 had been slowly meandering through the forest and left behind them wonderfully evident marks of their playfulness in the shape of pulled down branches, rooted-up trees and holes of two feet dug up by their tusks. They had broken a new road through the bush and we were not slow in availing ourselves of the inviting prospect of coming up with them. Once a swamp blocked our way, which the elephants had passed but which our horses could not ford and we had to make a circuit of several miles. But we managed to regain the spoor on the other side.

Mile after mile we followed and it seemed to become no fresher. At 10:30 we had just passed a small meadow in the forest when we caught the once-heard-never-forgotten grumblings of the elephants. The wind was most favorable. In an instant we sent the horses, carriers, and natives back. So there were four of us: myself, a native hunter, an interpreter (Osman), and my head boy (Dangana). I had two .405 Winchesters and two French army rifles. We proceeded carefully to investigate the position of the game.

Nearer and nearer came the magnificent gurgling and grunting, sometimes sounding like organ notes. There is no word in the English language to describe that music in which an elephant indulges. Slowly, slowly. And after another 50 yards through the bushes loomed the giant slate grey colored bodies of the herd. Unconsciously I stopped but the hunter went on and motioned me to advance as well. Where he could go, I could go. We were 50 yards from the nearest animal. Quietly they continued munching on grass and leaves.

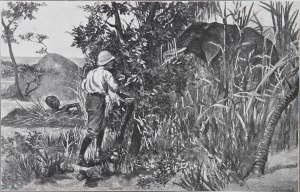

At about 40 yards we could see the little eyes twinkling, see their ears flap and their tails whisk. At 30 yards (how far was that hunter going? Was he going to creep right in amongst them?) I noticed several large beasts coming to us from the right. The hunter saw them too and finally stooped. Close by my side he kneeled behind a bush. There were no large trees that an elephant could not break or root up in an instant. There was nothing but scrub, brushwood, grass and a few small “shea” trees. If the elephants charged there was no running away from them, no tree to climb, no hole to hide in. But why think of running? I held in my hand a Winchester loaded with 5 hard-nosed bullets that would go through anything in the elephant — skin, flesh and bone.

Silently we watched the great beasts in front of us. They were evidently unconscious of our presence and continued feeding. The hunter touched my arm and pointed to the tusks of the mighty head on the left, another in front of us, and two or three on the right. There were before us altogether about 10 full grown elephants and 30 young ones (aged from one year to 20 years).

All these observations take some time to recount, but less than one minute had elapsed since we got the first glimpse of the herd. I fired my first shot just in front of the ear of the largest animal and another followed into the second largest of the herd. But there was no result. Soon the heads of all the younger animals were in the air, their large ears spread out like sails of ships before the wind, their trunks stretched snake-like forward sniffing the air. This way and that way surged the living mass of bodies, not knowing in which direction to turn, crushing trees and bushes like matchwood. We lay flat on the ground hardly daring to breathe. Mothers, anxious for their young, roared, the little ones screeched, and the older ones grunted and trumpeted. Then the leader found a way to the left. He moved and, closely pressed together, about 20 others followed. A sigh of relief rose from our hearts. None had charged.

Safe? No! The worst was yet to come. Suddenly, before us on our right loomed up the heads of six of the largest elephants bearing straight down upon us. They were 30 yards away and soon only 20. With feverish haste I raised my rifle and fired one, two, three shots. Still they were coming, and my nerves gave way and I ran like a hare. My boys had already disappeared. The whole world seemed full of elephants. Before me rose a small anthill. I wished I were only an ant and could creep into it. In an instant I was flat on the ground behind it, and behind me thundered the charge of the behemoths.

I had hardly reached the ground when I fired a shot at the neck of the nearest bull as he passed within a few yards. Then I lay still for a minute. This was the first time that I have trembled before game in Africa. The earth seemed to shake and all around seemed to be filled with roaring, trumpeting giants. I should be ashamed of myself for being frightened. But it was too much for my nerves. There was no protection in my rifle against six charging elephants. If there had only been one it would have been different.

So now it was in doubt as to who was being chased. Then all became still. Osman and the hunter had gone after the herd and Dangana lay 20 yards behind in the middle of a thorn bush. He had been with me to hunt buffalo and had not been afraid then. He had also been close to lions and never shown the white feather. He had walked with me right up to the elephants and shown no fear. But now his pluck was gone and a few minutes later he fell into an elephant trap (a hole 12 feet deep covered with grass). He had enough elephant hunting and begged to be excused for the following day.

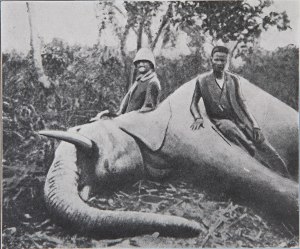

I looked at Dangana and he looked back at me. Where are all the elephants? There was a certain amount of blood. One or two seemed to have fallen, but they got up again. Neither was dead on the spot. I did not know what to think or say. But then a few yards further I came upon a large bull. He stood sideways to us about 40 yards off. I knelt down and gave him a bullet through the ear. He turned around then looked mischievously in our direction but evidently he did not see us. I fired another round into his shoulder. Then he charged. But a third round into the head brought him finally to the ground. With a roar and a crash he fell. One tusk was buried deep into the earth and his body firmly wedged between two small trees.

Calling the men I left them with the dead elephant and followed the herd for the rest of that day and the next but never found the other wounded animal. What was the reason they did not fall on the spot? Were all my shots placed incorrectly? I had been informed that a shot through the ear would kill on the spot but neither a shot through the ear or the eye ever brought down an elephant for me. After the head had been cut off, I had the skull placed against a tree and fired at it from different directions and I found that a bullet placed at the root of the trunk was the one that penetrated through to the brain every time. All the other shots were unsafe, except for a shot half way between the ear and the eye.

The natives of the village were delighted with all the meat and became our fast friends.–Selected and edited by Ellen Enzler-Herring of Trophy Room Books