Armchair Safari – Giants of the Forest – African Hunting Adventures

Two days with gray giants. It has always been an open question among hunters whether the lion, elephant, rhinoceros or buffalo should be entitled “the King of Beasts.” Each bases his claim on man-killing ability. To me this has always seemed illogical. The mamba and cobra are equally as efficient man-killers but none has ever claimed kingship for either. It would seem that human egotism induces man to seek consolation for defeat by exalting the animals he hunts. By exalting those which most frequently defeat him.

Two days with gray giants. It has always been an open question among hunters whether the lion, elephant, rhinoceros or buffalo should be entitled “the King of Beasts.” Each bases his claim on man-killing ability. To me this has always seemed illogical. The mamba and cobra are equally as efficient man-killers but none has ever claimed kingship for either. It would seem that human egotism induces man to seek consolation for defeat by exalting the animals he hunts. By exalting those which most frequently defeat him.

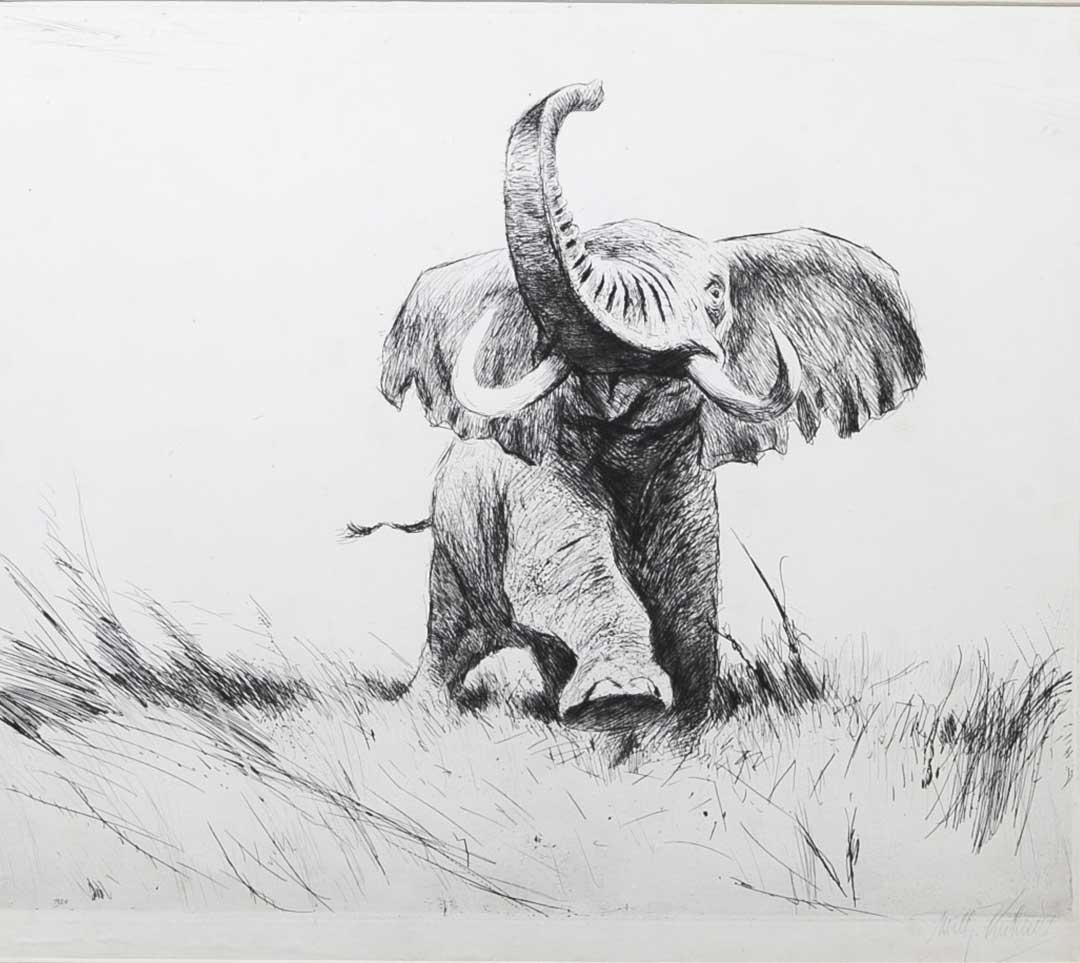

Apart from danger to the hunter, however, and fully recognizing that there is no supreme ruler among animals, the elephant is undoubtedly king of the forest. No animal that lives can attack him successfully. Neither dense bush nor great rivers can stay his progress. And, speed, strength, wisdom and courage he possesses in abundance.

Sixteen years ago I embarked on my first elephant hunt in company with an Irish-American and one of those “bad boys” a reputable English family sometimes exiles for its greater peace of mind. This was in a district very close to the Katanga border. Leaving camp at daybreak, we found spoor at a “pan” a few miles away and the Irish-American, whom I will call Jack Murphy, gave his opinion that the beasts had left the pan after midnight.

This he deduced from the fact that there were dew traces on the underside of leaves broken off by the elephants, and as the dew had not formed until after midnight, these must have been broken off after that hour. The spoor showed that three bulls had drunk, and that two were exceptionally large bulls, likely to be worth following for the ivory they carried.

The natives named a pan 40 miles away on the route the elephants had taken, as being the next water. We were probably six hours behind the grey giants, but as there were several feeding grounds en route, we hoped to come up with them long before they reached the pan. Having drunk during the night, elephants will not usually stay on feeding grounds and sleep during hot hours. Their journeys to water are made at night, especially when far away, and once headed on that quest they will cover 60 miles without pause, in about 10 hours if necessary.

We had traveled about 10 miles when one of our three native water carriers gave a startled yell and sprang aside, letting the calabash of water fall to the ground. Wheeling swiftly, we three white men were just in time to see our head boy raise the shotgun he carried, and blow the head off a vicious-looking green mamba under which the water carrier had almost passed. This incident was unfortunate, not only on account of the lost water, but because we feared the gunshot might alarm the “phunts” if they were anywhere within two miles. Although they are nearly blind, they are wonderfully keen of scent and hearing.

Our fears were unfortunately justified. A mile further on we found the spoor diverged from the broad trail and wound aimlessly hither and yon amid the trees. Yet not aimlessly, for bark with the sap still wet hung in strips from the trees, and tall saplings broken off showed that the elephants had fed upon their leaf-crowned tops within the hour. On every side were broken trees and saplings, and peeled off bark, dead dried and old, proving that this was a favorite feeding ground of the forest kings. Despite assertions to the contrary, elephants are wasteful feeders. A wide range and specialized diet immunize them from the hunger which teaches economy. There was no sign of the bulls we followed, but a mile further on we found their tracks again on the elephant trail. But longer strides and deeper depressions showed an accelerated pace.

Jack cursed and said, “We pay for that damned shot with another 30 miles of walking before dark. Well, do we go on or go back?”

Ted replied, “If my bank balance were more robust, I’d say go back. But it’s anemic and present and money from home is six weeks away. I vote for the ivory.”

With this I agreed. Money from home never came my way. So we proceeded, but it was three weary and exhausted men who arrived at the Malundi pan that night in the moonlight and our six boys were in little better shape. Having taken water and washed, we retired two miles into the forest and camped, making a scant meal of dry bread, biltong and water. This and one blanket were all that Jack allowed us on elephant trails.

With this I agreed. Money from home never came my way. So we proceeded, but it was three weary and exhausted men who arrived at the Malundi pan that night in the moonlight and our six boys were in little better shape. Having taken water and washed, we retired two miles into the forest and camped, making a scant meal of dry bread, biltong and water. This and one blanket were all that Jack allowed us on elephant trails.

Ten miles before reaching the pan, the spoor turned into the forest, but we were bound to push on for water, and we knew that sooner or later they would come to the pan. It was the following night before they did so. Had I not shot a sable five miles away we would have slept with empty stomachs, as we dare not shoot near water.

During that second night, trumpeting in the direction of the water told us that more than three bulls had arrived. On examination at dawn, we found that a small mixed herd had watered during the night. They headed in a direction opposite to our home camp, but we stuck to the trail. About noon, Jack caught my arm and pointed ahead, at the same time motioning the natives to halt. Peering through the trees I discerned a motionless gray shadow about 100 yards ahead, and then another, and another. Six in all. Jack went ahead to place the herd.

With two of the natives he disappeared silently among the trees. For nearly an hour we saw him at intervals, appearing and disappearing as he progressed noiselessly in a wide circle ahead of the elephants in front of us. On return he announced, “I have counted 12, all ahead of us, and the wind is in our favor. But the big bulls are on the other side of the six cows. We must pass by them to get at the bulls. Risky, but it can’t be helped.”

Following him silently, we at last outflanked the cows and calves, eventually discerning the sleeping bulls on the farther edge of the herd, standing 30-80 meters apart. Stopping about 30 paces from the nearest Jack said, “When I raise my rifle above my head, aim at the height of the shoulder, but a foot or more behind it. Count to 10 and then fire. When they stampede, don’t move.”

He took up a position about the same distance from the center bull, while Ted worked to the right. Standing with taut nerves and waiting for the signal, I surveyed the mighty bulk ahead of me, and my rifle seemed a puny weapon to deal death to a giant. It was only five minutes until the signal came, but it seemed like hours. Jack fired, and I concentrated all my attention on the matter in hand.

I had only counted to eight when Ted’s rifle shattered the echoes. With no more ado I pulled the trigger just as the grey bulk ahead started into life. His huge trunk whirled skyward. Five second later I was too paralyzed by the cacophony to move.

The silent forest suddenly became a pandemonium. The air vibrated with furious trumpeting. Grown trees and saplings crashed in all directions as they collapsed in impact of the giants. The earth shook and trembled as if it were an avalanche before which the forest seemed to bow in all directions. Jack’s advice not to move seemed superfluous. I wanted to move but the forest was filled with crashing forms and there seemed no avenue of escape from the living cyclone.

I stood still and prayed that the spot I chose would not be in the giants’ path. I heard two rifle shots and was conscious of gigantic, screaming forms whirling past me to the accompaniment of crashing trees. Then the tempest of sound receded, I felt a hand on my shoulder. Jack said, “Wake up, don’t let the rumpus scare you. Give me a hand with Ted. He’s hurt.”

A hundred yards away, Ted lay groaning with his right leg and two ribs broken. A cow directly in his path charged. Jack fired two heart shots but she seized Ted with her trunk and whirled him aloft before she fell. The impact with a tree as he fell did the damage. With two rifles and strips from blankets, and fractures being simple, we were able to get him to a Belgian hospital a week later. Alas my first elephant hunt was Ted’s last. The bull he had fired at was found by natives a week later, 50 miles away. But the other two we found before sunset, within three miles. The cow lay dead a few miles from where she had dropped Ted.

We buried over 300 pounds of ivory and three weeks later, the manager of a certain firm came with me on a shooting trip and bought the ivory as it lay for a tidy sum.

The second hunting day I will describe occurred years later and gave even greater thrills though by that time I was more used to the uproar of a panic driven herd. Accompanied by an Australian friend, Ben, we got up at 2:30 a.m. to track elephants that likely had a two and a half hour head start on us. We had to start after them at dawn. Two boys carried water bags and dried meat while 10 others carried food and blankets. We marched in silence for an hour for there is something in the bush of the forest at dawn which forbids speech. Then, as the sunlight dispersed the last shadows and revealed each leaf and twig in golden brightness, speech again became the interpreter of the senses.

We halted to examine broad shallow depressions in the path and Ben measured two of them. He declared them to be a herd of 10, one large but likely the herd we had encountered a week before. Ben said, “They have cost us 240 miles of walking already. It’s time we collected some reward.” Ben was a good shot, utterly reckless and he found anything less than 5,000 miles of solitude too limited for the scope of his activities.

For hours we trudged along the broad trail. The sun climbed higher and the heat became overpowering even in the shade. Water had to be used sparingly, for the elephants were headed for a pan 45 miles away, and there was no other water en route. We halted for 30 minutes at midday and then carried onward again over sand that seemed hot even over thick boots.

At 3 p.m. Ben suddenly stated, “Steady partner. We’re on them.” Wiping my eyes, I followed his pointing finger. In the shade of a tree 100 yards ahead I discerned a slim gray patch. It was motionless and could have been mistaken for an ant heap. Now we knew that our success depended on caution. The air was already motionless, but what little there was came from the elephants to us. Lucky for us. Approaching cautiously to within 50 yards, the gray patch revealed a mighty bull sleeping in the woods, standing facing us. From where we stood, we could count four other gray shapes farther along the trail, beyond the gray bull. Nine altogether. There was a big bull to my right. I would shoot it while Ben was to shoot a bull standing almost broadside. He warned me not to leave any behind me to get our wind.

I moved slowly toward “my” bull and another shape became discernible about 50 yards away. Ben meanwhile moved slowly to the towering shape 30 yards ahead of him. Then he told his native to “turn the bull to the left.” Knowing what was required the boy moved 10 yards away, picking up a handful of dry twigs along the way. Then he halted and broke a twig. At the soft snapping sound, two great ears moved forward and remained spread. The elephant was listening. Moving silently forward, the native halted again about 40 yards from the bull and snapped another twig. Slowly the beast turned and strained to catch any telltale movement.

I moved slowly toward “my” bull and another shape became discernible about 50 yards away. Ben meanwhile moved slowly to the towering shape 30 yards ahead of him. Then he told his native to “turn the bull to the left.” Knowing what was required the boy moved 10 yards away, picking up a handful of dry twigs along the way. Then he halted and broke a twig. At the soft snapping sound, two great ears moved forward and remained spread. The elephant was listening. Moving silently forward, the native halted again about 40 yards from the bull and snapped another twig. Slowly the beast turned and strained to catch any telltale movement.

This maneuver brought the left side facing Ben and gave him the chance for a lung shot. Ben knew he was not close enough for a brain shot, and in the position the elephant was, there was no chance for a heart shot. So it would be a shot into the great expanse of lungs. I signaled to Ben that three more were located. So now only one was unaccounted for. Trusting to luck that the missing beast was not behind us, Ben gave the signal to shoot. I relied, “Understood.” As my .450 Express boomed, his 11 mm Mauser almost synchronized and the reports sounded as one.

In an instant, echoes of the shots were drowned in an inferno of sound and the drowsy shapes leapt to crashing, pulsating life. A chorus of trumpeted screams and a crashing of bush and trees yielded to the shock of great bodies. The bulls went upwind and the very air they displaced seemed to strike us in a swirling rush.

Years ago this would have left me shaking. But those days were past. Even as the big bull Ben had shot raised its trunk in a reverberating scream of rage, his rifle bolt drove another cartridge home. But, as though untouched, the leader of the herd swept onward and away from him. Meanwhile I placed a second bullet in the bull I had fired at and then concentrated anxious attention to my rear. Lucky I did so. From behind a young bull broke cover and charged directly at me from 50 yards. Hastily I fired two shots while Ben’s Mauser rang out. Then I heard his shouts, “Run! To my left!” And run I did.

As the animal swerved again after me, Ben fired another shot. There was a slight stumble, a hesitating recovery, and the young bull headed off in pursuit of the herd. Five minutes later we took up the trail, sending one native to follow the young bull that had almost ended my career.

There was no trouble following the herd. Keeping in the direction of the elephant path they had followed in single file when undisturbed, we noted they were running abreast through the bush. Broken trees, saplings and brush revealed their furious passage. We had gone about two miles when the native noticed them standing still. Approaching closer, we noted the reason for their halt. The big bull Ben had fired at reached the limit of its endurance and stood, supported on either side by two smaller bulls. Leaning their powerful shoulders against their stricken comrade, they aided his desperate efforts to regain his feet. But even their great strength was to no avail. As we watched the big bull crashed helplessly forward.

One of his two assistants was obviously the bull I had shot at and wounded. He was still strong and full of it. So we moved quietly forward, hoping to include him “in the bag.” Then a stick snapped underfoot and with incredible swiftness the two bulls wheeled in our direction. As if on signal, the cows came into line. Just as a native screamed to warn us, seven colossal figured charged down on our puny forms. I felt like a beetle in a boot.

Ben’s innate recklessness surged and he shouted at the boy to run while he aimed at the chest of the center bull, shouting at me to fire also. I worked my bolt frantically, sending bullets into the animal I had originally fired at. Ben’s Mauser continued to roar beside me. Then, at 20 paces, the target stumbled and leaned heavily against the bull on his right. That bull in turn leaned on two cows to his right, then closed in like a troop of soldiers on parade, and then suddenly the herd swung to the right, the flank animal passing within 10 paces of where we stood.

Calling the natives we walked over to the great leader which had fallen first. The men emerged looking gray rather than black. Ben told a couple to return to camp for supplies and that we would camp by the big bull that night. Then we followed the herd into the forest and had gone perhaps a mile when a huge gray mound showed where another monarch had fallen. We found the second bull, my original target. The natives arrived to chop out the tusks. Ben found where my shot had never reached the lungs because the shot splintered, like a soft nose. He said the firm that manufactured that ammo might be tried one day for manslaughter. I liked the British ammo, but knew that one day I should switch to American or German made. Then Ben mused, “The two minutes we lived through an hour ago were an experience a millionaire could not buy.”

We estimated the weight of ivory at 350 pounds. And for that we had walked 350 miles…AND risked our lives. That was average for those days. And risking one’s life teaches you not to get conceited about the value of it! After all, in elephant hunting the risk of sudden danger is ever present. The thrill of danger, hundreds of miles of walking, hunger, hardship and thirst all give a zest to life and a prideful efficiency to mind and body. I raised a glass to Selous and all the others who had hunted elephants before.

Darkness had fallen when we returned to camp and we settled in for an uncomfortable night. But we slept well.–Selected and Edited by Ellen Enzler-Herring of Trophy Room Books