Armchair Safari – Denker Spirit

Typically, our selection for this series is from out-of-print big game hunting books. However, Denker’s recently released (in English) book, About the Spirit of the African Wilderness, has garnered so much acclaim from professionals, hunter-readers and book collectors that we have decided to offer an excerpt here.

Part 1: A Potentially Dangerous Animal. At one time I was hunting with a humorous Romanian client, possessed of a ready wit, but without experience hunting elephants. He always had to have the last say.

During the first days we tracked down an elephant which became aware of us and advanced in a threatening way, with a few quick steps, head raised and ears spread wide. It was a typical situation, which, from ignorance or to dramatize the matter, at times is described as a mock charge. This is nothing more than a threatening or intimidating pose by the bull. Because of my principles – the bull was not shootable- not to play around with elephants in such situations, I called to the client in a hushed voice, “Get away!” – but still had to chase him with a hand gesture.

I assume that this situation, in which I ran away so decidedly, appeared not dramatic, and it led the client to perceive that a charging elephant was neither fast nor particularly dangerous.

A few days later we took up the tracks of two bulls, one of which was the rugged imprint of an old bull. We were hunting for a non-trophy bull. On these hunts I always tried to take old bulls of inferior quality trophy potential. This countered the off-take of big old tuskers, balanced the structure and ensured that bulls of inferior trophy potential would not pass on their genes disproportionately.

It was October. We caught up with the two bulls in the intense midday heat in a matted, shade-less sickle-bush thicket, with a few isolated camel-thorn trees in the area. In the shade of one spreading tree the bulls were standing. We could see the line of their backs above the matted shrub, but were not able to assess their trophy quality.

We had to get closer. Carefully and silently as possible I lead our small group through the matted bush towards the camel-thorn tree, until, after rounding a big wait-a-bit thorn with thorny branches protruding in all directions, we could see the bulls more clearly through gaps in the vegetation. They were perhaps 50 paces away and I immediately realized that the old bull was much too big for our purpose and therefore not shootable. It was midday and the wind was in our favor. I wanted to retreat.

The client, however, was reluctant and wanted to look at the bulls. In this moment a gust of wind went directly in the direction of the elephants, and I could see that the old bull, which until then had stood in the shade with lowered head, flapping his ears, suddenly was alerted and listened, then raised his trunk into the wind. We froze in tense anticipation. Meanwhile the gust of wind died down and soon the elephant started to flap his ears again, and even took up some cool sand with his trunk to throw it over his head and shoulders, sighing deeply. Again the wind suddenly rose and this time the bull swung round to look in our direction with head raised high.

It became clear to me that this was an irritable bull, not inclined to abandon his position in the shade, because normally the bulls would already have rushed off after getting the first whiff of our scent. Amidst the matted brushwood, in which it was difficult to run freely, we stood with our backs against a big thorn bush, me in the front, next to me the client and the trackers next to him. In a hushed voice I told the client that we must retreat and even be ready to run at any moment. To this he replied, “I’m very fast,” and told one of the trackers to hand him his video camera. The San (tracker) put down the water canteen he held in his hand, and started to dig for the camera in the rucksack. In this moment, the bull lowered his head and rushed towards us, uttering a few deafening screams of rage.

He had already covered half the distance that separated us before the San picked up the water canteen again. The other two trackers were running already, but until the client made room in the narrow space between the bushes for me to run as well, it was too late. It was no longer possible for me to run away looking back over my shoulder. I had to retreat backwards to keep focused on the bull to immediately shoot if it became necessary.

In frightening, awe-inspiring force the elephant came rushing on, the scraggy twigs of the sickle bushes were bursting underneath, his feet cracking while I tried to get away backwards. In helpless slowness, a split second realization flashed through my mind that I could only shoot as a last resort, as possibly a trophy bull could be removed from my quota. Moreover, the bull was likely to stop at the last moment. In that instant I tripped over a branch or a root lying on the ground and fell over backwards into a sickle-bush. I struggled to regain my feet immediately, the elephant was almost on top of me. I don’t know when I threw over the safety catch of my rifle and what induced me to risk a last attempt to stop the bull without having to shoot him. I fired a shot through his widespread left ear, close to his head. I worked the bolt of my rifle again in a mad hurry, as to follow up with a second shot into his brain should he not stop. Finally I noticed with great relief, yet still full of deeply unsettled alarm, that the bull had stopped abruptly at the bang of the rifle and raised his head high above the thorns, while I still stepped backwards.

I practically glided away (please do not consider this an exaggeration, that is exactly the impression I had) from underneath the feet of the elephant towering above me. He was swaying his huge head in strange, noiseless smoothness to the left and right. It was an incredibly impressive sight: with ears spread wide, the head appeared like a grey wall three meters wide and full of furrows and wrinkles. His small eyes, sparkled viciously, foamy tear liquid glistened in their corners, tusks pierced the air, and the trunk hung down, only the tip switching to and fro.

It appeared as if time was standing still, while I was gliding away backwards, the elephant swaying his head, raised majestically high above the brushwood, from side to side, staring down on me, until at last I had put enough distance between us to allow me to turn around and run away, only looking back over my shoulder. In this moment the elephant, too, lowered its head and ran away in the opposite direction.

Now my companions reappeared from behind the bushes. The client immediately started talking again and offered me some water to clean a gaping cut, which a sharp sickle-bush thorn had ripped into my right forearm when I fell (even today I carry this scar as a souvenir of that day). Motioning away brusquely, I bellowed to him to shut up and gave him a proper dressing-down, which I closed saying, “It was very dangerous!”

To this he replied with great indignations, “Yes, of course – I know it was very dangerous because he made such a big noise!” I wanted to slap his face. He still had to have the final say. But his indignation came across in such a funny way that, in spite of all the tension, I laughed.

The following day I came up with three old bulls, amongst which there was an ancient bull with very poor ivory. I was determined to rebuke the client. The bulls moved along in front of us, leisurely in dispersed fashion. I stuck to the heels of the ancient bull, closing in more and more. When I turned around I noticed that the client was very reluctant to follow and I repeatedly had to motion him on. He followed reluctantly, crouched down very low, eyes wide open.

When later we sat around the fallen bull, he remarked in his somewhat broken English, “After yesterday experience, it was good not to be so close.”

Had I not continued to back out after the bull stopped when I shot him through the ear, it is questionable whether the bull eventually would have turned to run, or whether in the end, I would have been forced to shoot in self defense. Contrary to the charge of a lion where one can only stand one’s ground in the hope that it is only a mock charge in which the lion will break off in the last moment or otherwise shoot as a last resort. Flight in the case of a predator generally triggers the reflex to pursue and bring down the fleeing. An elephant only intends to put the opponent to flight with a mock charge. If he succeeds, the elephant turns in satisfaction. Should he fail in this intention, in young bulls there is often a series of repeated demonstrations of rage, until the bull, without being able to summon the determination to charge, retreats in a mood of pent up anger mixed with uncertainty.

Old bulls tend to turn after a short mock charge and retreat. Very self-confident experienced bulls, however, easily go over into a determined charge if they do not manage to make themselves respected with a mock charge. As the era when one could shoot any threatening elephant in “self defense” are over, one should always retreat. In doing so, one should be able and prepared to stop the elephant with a brain shot if need be. But the case I have just related is the typical scenario from which the presumption was born that a charging elephant is easily stopped.

Part Two: To the West of Khadum (My first hundred-pounder taken by a client)

On an icy winter morning, with two trackers and a German Client Carl Fischer, I eventually trudged down that broad elephant path towards the waterhole. When, on reaching the edge of the rupture where the ground drops towards the waterhole, we momentarily checked our steps, let our eyes wander, and immediately realized that movement had occurred here in the meantime. Broad elephant paths radiated towards the water, at the edge of which (until recently seamlessly merging with the grassland in the clearing) a broad fringe of bare, trampled soil appeared.

Still stiff from the morning chill, we stepped down and walked around the waterhole, then began searching the wider surroundings, while the client, who at first had been standing in the warming rays of the sun, sat down in the shade when the sun rose higher.

I moved far away from the water on a game trail leading northwest, crossing back south, to make a wide semi-circle around the waterhole. On difficult, grass covered ground, I came on a partial print on an extraordinary coarse elephant track. Actually I had hoped to come on to a good track. Here, far away from the water and leading away from it, it would be easier to pick up and hold than in the confusion of tracks near the water. But the track onto which I came did not lead away from the water but towards it, not directly, but rather obliquely. Meanwhile it became warm and I extricated my left arm and shoulder from the sleeve of my heavy jacket, carrying it on my right shoulder, while slowly progressing on the trail.

It was difficult. Progress was slow. But I was working towards the water where the track got lost again in the maze of tracks. At the water we would first have to find the way the bull departed. It appeared a waste of time to me and I thus left the trail for the time being hoping that the Bushmen meanwhile would have found the exit tracks and returned to the water.

Hopefully, my eyes roamed over the wide country, the air was filled with the melodic call of spotted sand grouse circling over the water to eventually, half folding their wings, descend in small groups to the water, from which other coveys were rising. The air by now began to shimmer, although short, unpleasant gusts of wind still moved the grass. It was a peculiar, yet typical, winter morning in the northern Kalahari.

Near the water, sitting in the shade next to the client, I came onto the trackers, who, shrugging their shoulders unconcerned, said they could not tell me anything. (I missed my old trackers.) There followed hectic searching. I eventually put one of the trackers onto the prominent track, to work on that while I crossed to the Khadum border with the other one. In their opinion, the big bull had crossed into the park together with three other bulls. Here I saw that indeed four elephants had returned to the park, but they were meaningless tracks.

I was just returning to the water, annoyed and taking big strides, when the first tracker came running. He had found the elephant, which had not been at the water at all, but was feeding in the vicinity and right now was coming to the water. Unfortunately, the tracker, in his haste to inform us, ran into the path of the oncoming bull, so that the latter, without fail, would get human scent.

In a hurry, we set out, and came to the place where the elephant, as I had anticipated, came onto the spoor of the tracker. I could see from the tracks that the bull had recoiled and then swerved off in the direction of the Khadum border. In desperate haste we hurried after him. At the foot of a small dune the Bushmen lost the tracks and while they searched around, I stepped ahead full of inner unrest to peer ahead.

I had not yet reached the crest of a small rupture, when I saw head and shoulders of the moving elephant on the other side and quickly moved to be able to see the entire bull. I could fill volumes with big elephants I had seen at the beginning of a safari, but had not allowed to be shot, as I was uncertain of how heavy the ivory in the end would really be, and hoped to come onto an even bigger bull. Only eventually, when running out of time, we gladly would have taken them but could not find them again. However here, it was only the second day, but there were no such doubts.

I admit that, in the excitement which immediately gripped me once I was able to completely see him, and especially his tusks, I did not look at the elephant stepping along through the open woodland with weighty, swaying steps, in distanced carefulness. It was immediately clear that this was a true, old big tusker. I retreated into cover behind the crest of the dune, whistled towards client and trackers, and motioned them to me. To the client I signaled that he should chamber a round. He sensed that the moment was not suited to asking questions about the size of the elephant and weight of the tusks.

Flanking the elephant we hurried along. The bull stepped along leisurely, carrying his head low, just as if the mighty tusks he swayed, a bit to the left and then to the right with every step, are too heavy for him. The bony shoulders project up, the glaring sunlight accentuates the spine and paints a few harsh shadows on the bony pelvis area, and again places this magical glimmer onto the dark ivory. We pass him and swerve to the side and position ourselves in the path of the oncoming bull.

But before the bull is close enough for a brain shot, the wind eddies. The elephant recoils, raises his head and turns, and there he is hit by Fischer’s shot to the shoulder. He turns to run again, and again he is hit by a shot. The mortally wounded bull swings around again in a dramatic gesture, shakes the head that the ears slap loudly against his shoulders, and then raises his head in a threatening pose, ears widespread towards us, while blood is streaming from his trunk. There he is hit with Fischer’s third shot and collapses.

Much is to be read about emotions of grief, which hunters experience when stepping up to a slain elephant. I have experienced that hunters, I am almost inclined to say demonstratively, burst out in tears when we stood at a slain bull, so much that the situation at times became awkward for me and Bushmen, who were entirely unable to understand this. I myself do not know such feelings. Although in hindsight after a bad hunt I at times felt disgust or in certain situations compassion, but I would never hunt an animal if afterwards I would have to bewail my action.

Even today I clearly see the picture when the big old bull over there turned in a dramatic gesture to accept battle with head raised high and ears spread wide, the mighty tusks piercing the air, while blood was streaming from his trunk, and I recall it not without inner conflict. But my emotions after having hunted an elephant always have been those of joyful excitement, and slowly, when after the first inspection we sat down in some nearby shade to contemplate the experience, the first joyful excitement gave way to feelings of satisfaction and awe.

When the old warrior collapsed, I hurried over, fully anticipating inner unrest and in stepping up (I still recall details in rare clarity) – realized that the fat cushions on the upper side of the feet were shriveled up. It thus had to be not only an old, but also rather ancient bull. My eye at the same time were magically drawn to the tusks.

I walked around this colossus lying on his right side, along the spine, holding the loaded rifle (supported on my hipbone) at the pistol grip with my right hand in case the bull should rise again. I stepped up to the head from the rear and felt for any reflex in the eye. All the time, with difficulty, did I manage to take my eyes off the tusk jutting up. After realizing there were no reflexes left, I brought the rifle down to unload it. At last, as a last measure of precaution still from the rear, I touched the ivory and tried to span it with my hands.

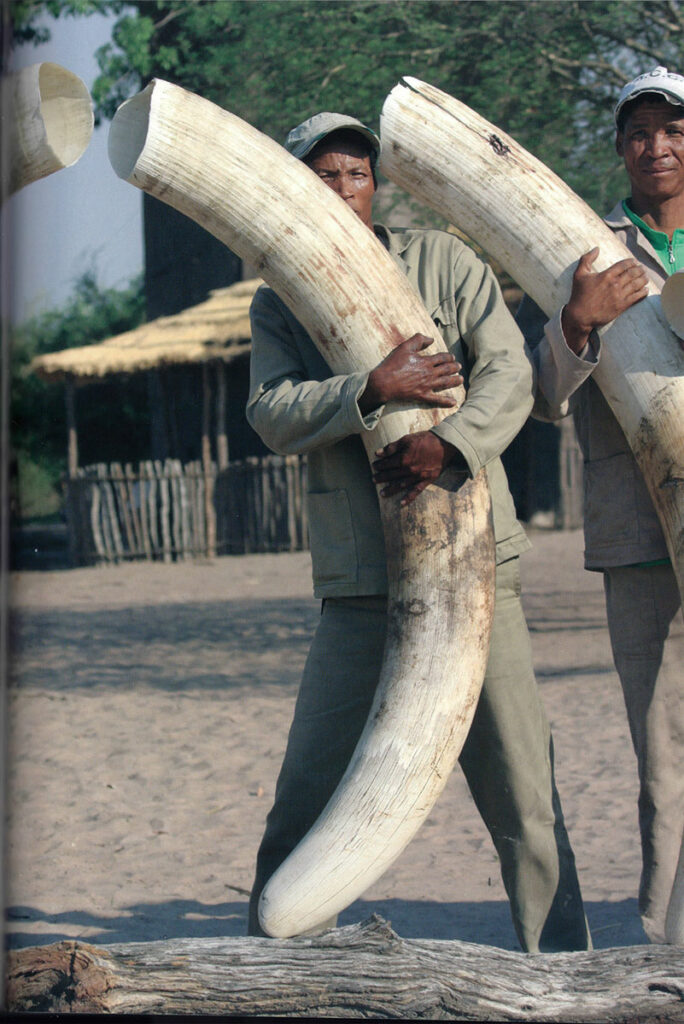

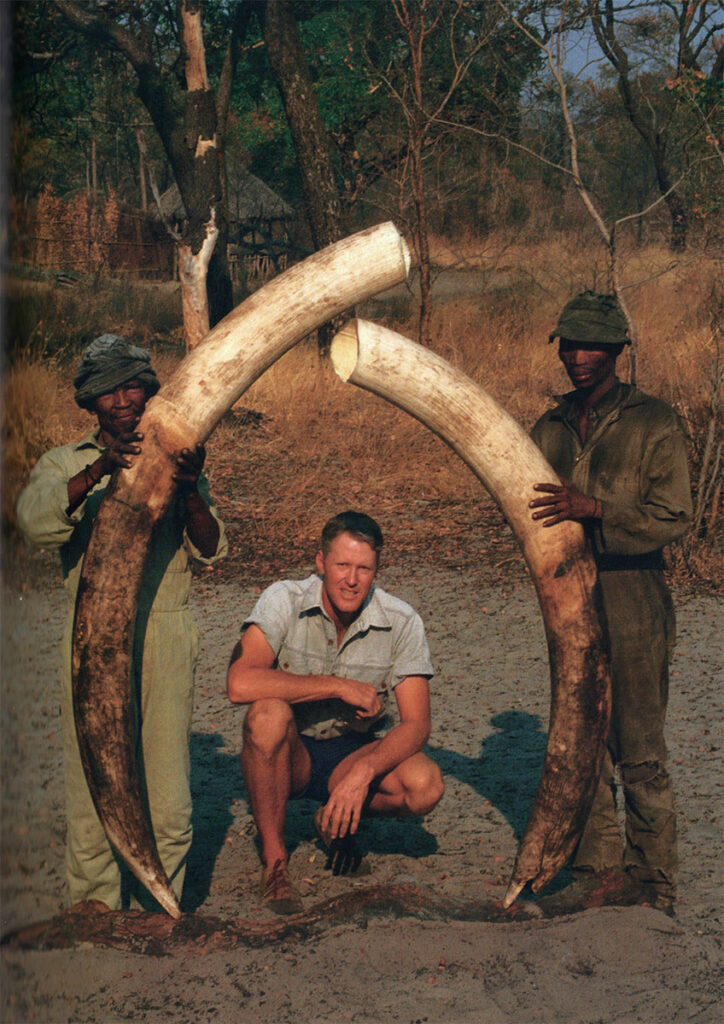

The emotions which spread inside me, when I realized I was unable to span the tusks with my hands by a large margin, and that moreover they tapered very slowly towards the tip – when I fully realized how big the bull was, are amongst the greatest moments of my life. After the first euphoria subsided we sat down in the shade to drink something, then got up again to walk around the elephant, admired and touched the mighty, dark ivory protruding six full spans of my hand from the huge head in the somewhat longer right tusk, lifted the tattered ear and let it slap back again, inspected the calloused soles of the feet and the hairless tip of the tail and it fully dawned on us that we were standing in front of an ancient big tusker. It appeared as if my fondest dreams had come true.

Bear in mind that at the time the general feeling was that there were no more 100-pounders. For almost 15 years no 100-pounder had been taken. After the pains of the last seven years, although we had taken some bulls in the 70-80 pound class (exceptional for the time), I had stopped dreaming of such things. Now, when I had reason to assume and hope, that the ivory of this bull might crack the magical 100-pound limit, it appeared as if I was granted the good fortune to turn back the clock for a precious moment to enjoy the great moment of mystical fascination which goes with shooting a 100-pounder.

In that moment I could not imagine that my clients in the coming years would still bag several outstanding tuskers, two of which carried even heavier ivory than the first 100-pounders of the 1999 season. They were always great moments, but never again did feelings flood through me as they did then, when it appeared as if a lost world had reappeared for a short moment.

When, in the coming days, we cut up the elephant and cleaned the skull I noted that the tusks were somewhat askew in the skull. It appeared that the left was more curved upward and the right one pointing down, more straight. This was not only the big bull whose right tusk imprint had tantalized me so much at the Xeidang waterholes, but moreover this was the big tusker which I had at first pardoned seven years ago at Mataza.–Selected and Edited by Ellen Enzler-Herring of Trophy Room Books