Armchair Safari – African Hunting Among the Thomas (in Portuguese East Africa)

From the very inception of our trip, lion rumors, lion stories, lion lore and lion alarms had enlivened our days and nights. Upon reviewing the graduated steps that led to a successful encounter with the King of Beasts, it is amazing to find how much of the thrill of shooting dangerous game lies in the process of cumulative anticipation. I believe that most men are constitutionally incapable of fear at the actual moment of danger and that exactly the same proportion is consistently scared at the thought of peril. A man deserves a certain amount of credit for entering the danger zone, but once it is upon him, the probabilities are that he will become as unconscious of his movements as if he had been tapped on the head with a hammer.

There are two aspects of big game shooting that are not often mentioned in print. One is the state of psychic suspension in moments of danger and excitement carried to a high pitch. The other is that however high-powered the gun, none but the first bullet to hit produces what is technically known as shock. Another observation: when food is plenty, well trained trackers can be held in leash if they respect the sportsmen with whom they are working. But in times of famine nothing can restrain some members of the black fraternity from crossing into open revolt at passing up any chance to increase the larder.

The question of sustenance does not enter into pursuit of the lion, which is a sensation without parallel whether from the point of view of the native or the white man. Snakes aside, the lion, wounded or unwounded, is the only animal in Africa to inspire unqualified fear in the inhabitants. They do not want to eat him; they only want to avoid being eaten. Calm reason tells the hunter that there has been a surprising equality in death to the hunter from Cape buffalo, elephant and lion so many accord them even honors as man-killers.

But the lion represents the supreme gamut of the unexpected, leaping in an instant from the basest cowardice to the overtopping peak of roaring valor. It was at ‘Npuxanyane on the banks of the ‘Nyasune that lion talk began to push forward. Our trackers were cautious. Many safaris go out with the avowed intention of getting a lion (without of course putting the safari in harm’s way) but many return empty handed. The report came to us of a slaughter of 14 goats, 2 pigs and a dog at a kraal only a few miles away. We explained to the men that if a lion were taken, everyone would receive a payment, and extra to the man who brought in news of fresh spoor. The men do not understand that in spite of the value of the elephant’s tusks, why we are prepared to pay more for a lion trophy and for an elephant. Finally they understand what we want to hunt.

We get packed up and start for the river. We get to the kraal and are disappointed to learn that the lion incident happened so long ago that its details have faded from memory. Angry, we push on further into lion country but there is a total absence of lion sign. At night, the sentry stands listening to whatever caused one of the horses to break loose. But he says it was nothing. The next morning we find spoor of five lions. It is no use to swear at the man. He answers all of our questions with the excuse that nothing could have been done at night.

However, we take up the spoor and follow it through miles of iziono forest until it comes out on an enormous plain. Before us is a vast oval sea of tufted grass, knee high and soggy underfoot. Away to the right are patches of high reeds and beyond them, the silvery gleam of open water. The trail leads diagonally across the open. To save time, two scouts are sent straight across to examine the far rim of sand that borders the vlei. We abandon our horses and on foot pick up the spoor once more. It is early but the heat is already terrific.

The spoor freshens. We see the recent kill of a muskrat and the smell of lion cloys the atmosphere. The trackers cast their eyes far ahead, studying the grass and reeds for some tell tale movement. When we reached mid plain, half a mile from either side, the sound of a whistle reached us. We looked back to see one man holding his hand high, signaling that he had found the spoor. Striking directly across the plain, we joined him. He was so still that we thought he might have bad news; but turned out that he was quiet because he thought that the lions might be watching him from the nearest thicket.

The trail was fresh and there in the sand was written the story of a family frolic. We concluded that in the heat of the day the lions were lying in the nearest patch of jungle. We stared up the slope while giving some men instructions on where to bring our horses. Blissfully ignorant of the anticlimax in store for us, we followed the spoor with steadily diminishing pace and increased caution, only to come upon their day bed to find it warm, but vacated. The lions decided not to wait for us. With arms aching from holding guns at the ready during a tense half hour, we plunged forward on the deeply indented spoor at high speed. Down to the plain it led us and again into a small but thick clump of high grass.

Here a halt was called and the reluctant beaters ordered into line. As the boldest of them cut across the wind to take his position, he stopped suddenly, turned and grinned. The beater was standing only 20 paces from us, on the other side of the clump and he had come upon the spoor. But again, the lions had moved on. And we did likewise. A new trail led us straight into the well-nigh impenetrable fastness of a mile-long mass of reeds fully 12 feet high. We approached the dense growth with sinking hearts but soon heard a low reverberating growl and a crashing rush. The tracker saw a tawny flash but only for a few seconds and the tall reeds bent violently. Then, only silence.

The expedients we used need not be fully narrated. We plowed through mud up to our knees and then met a barrier of rightly named sword-grass through which neither black nor white could pass without shedding blood. We frequently heard the lions, but always going away. Our position was untenable but we did not realize this until later. We set fire to the reeds, to no avail. We made for camp and it took two days to recover from our indispositions. Lions are supposedly common in the area where we hunted. But I never managed to actually lay eyes on but two of them.

The expedients we used need not be fully narrated. We plowed through mud up to our knees and then met a barrier of rightly named sword-grass through which neither black nor white could pass without shedding blood. We frequently heard the lions, but always going away. Our position was untenable but we did not realize this until later. We set fire to the reeds, to no avail. We made for camp and it took two days to recover from our indispositions. Lions are supposedly common in the area where we hunted. But I never managed to actually lay eyes on but two of them.

On the second day I managed to purchase a large, full grown goat, which would be used as bait. Night after night the goat would be tethered just outside the camp. But nothing worked. Perhaps the goat had the wrong smell. A week later we pensioned said goat off to our friend and returned to again search for spoor on foot. We killed an eland for the pot at Gumbo kraal. It was easily the premier of all our camps. The man who had not told us when the lion came in the middle of the night, returned again to report news of a lion. The news came from a woman who was looking for elephant for us. Not the most reliable news, but the only news. The woman led the safari and kept up quite a pace. When we reached her miserable abode, protected by a mere vestige of rotted encircling thorn hedges, they tracked rapidly the movements of the lion and then led us into the bush and put us on the spoor of his last get away. Through it all she never smiled or showed the slightest excitement. As we took off she stood watching with a clam look and seemed to settle all of us down as well.

We left horses and beaters behind and I myself led with my men. It was rolling, almost open country, dotted with clumps of a species of landolphia vine and very sparsely forested with temba and thorn trees. By good fortune the grass was less dry, fallen and scarcely knee high. For two miles we walked rapidly and on the easy spoor. Then the head tracker almost halted, arrested by some indication that just there the lion had been thinking of lying down for a nap. From that point on the trackers moved with a cautiousness that, by implication, started the blood pounding in our temples.

I thought about my previous missed shots and promised that this time I will be a little quicker, a little surer. That it never happens that way means nothing against a man’s habit of reconstructing conditions on experience. I thought about the first time I saw a lion in the bush at 10 paces, shot where the shoulder ought to be and by the guidance of a merciful God, hit a tree. What if that should happen to me again?

The head tracker suddenly stepped aside and pushed me ahead, whispering loudly as he did so. I did not know what he was saying but assumed it was about a lion. The word TSUTSUMA could mean anything. Perhaps it meant he is lying down, or he is running, or he is charging! For a ghastly moment I felt rattled. I was still standing in an agony of indecision when the tracker strode forward to pick up the spoor again. The explanation of the puzzling word was: he should have said TUTUMA (he is trotting off). But so great was his suppressed excitement under the mask of his outward calm, that he reverted to a little known dialect of his childhood and pronounced it in an unrecognizable explosive voice.

With a lift of his chin to signify that the lion had moved on, he led the way swiftly until the trail reached the spot where he had caught a glimpse of his quarry. Then he slowed down again and began working carefully, eyes fastened on the ground. Another of the trackers grunted boldly, seized another of the men by the arm and pointed out the lion, traveling in a direction that would keep him hidden from me for a minute or two. Resisting a monster temptation, my hunting partner hurried to my side and a moment later the great beast came into full sight, broadside, and about 80 yards away.

If fervent prayer can guide a bullet, mine traveled in a groove. The lion’s long body seemed to telescope and arch into the air. As it came down there was a second raking shot almost immediately after the first. The boys cried loudly with a deep-toned exaltation. Throwing caution to the wind, I rushed pell-mell after what might have been a wounded beast, caught sight of him moving away at a heavy lope and fired wildly. Then I came to my senses. If I had more experience I would have known by his actions and above all, by his silence, that he was very sick. But as it was, we took up the blood spoor with feelings in which exultation as yet had little part.

I finally came upon the lion lying between two trees, head up, eyes to the front. He did not turn to look at us and made no sound. For all intents and purposes he was a dead lion, but somehow visions of a roaring charge yet seethed through our brains. Still in the grip of excitement, I finished him off. He was average size but he was my own and had given me more thrills in five minutes than anything else I can remember. I am not a photographer so none of the pictures does him justice. There was nothing showy about his mane, but he had one and his teeth were long and sharp.

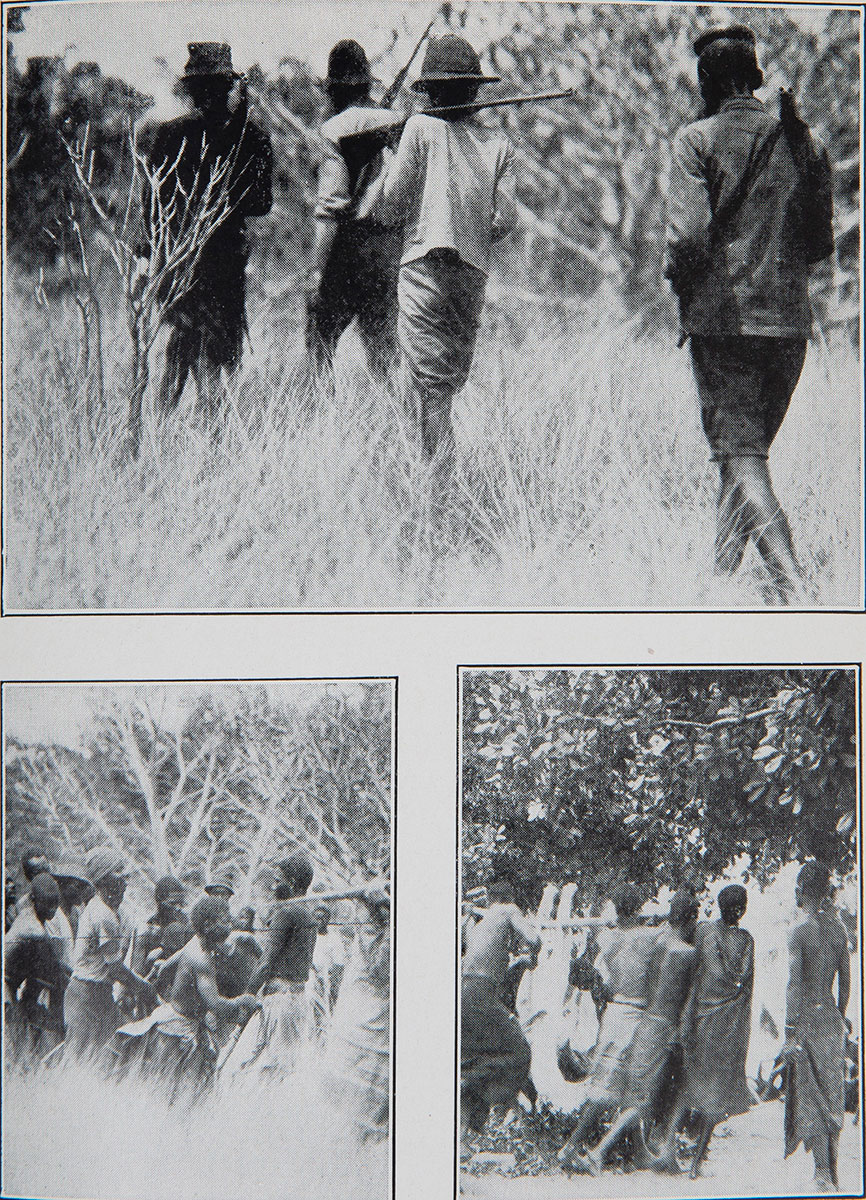

The men dragged him out, trussed him up and started for camp at such a swift pace that our horses were forced into a trot and finally into a lope. The boys raced alongside the bearers, diving in to relieve them every so often so that there was never a pause in the headlong rush. Throughout the journey back to camp the boys sang a song as only an African can master. The entire village came to meet us and everyone showed up to collect their reward. That night a great ball was staged in which everyone took part except the chiefs, the head trackers and our personal entourage. As the night wore on, so did we. Finally it was over. My hunting trip through the Thonga District had been a great success.–selected and edited by Ellen Enzler Herring of Trophy Room Books