Vines and Stalks: Hunting Vintage Blacktails In California

Clever Columbia Blacktails Rule The Vineyards in Coastal California.

By John Geiger

Neat rows of vines, heavy with grapes, carpeted 500 acres of Steinbeck Vineyards in Central California. The view of the vineyard from above looked as if God had dragged a comb over rolling hills.

The area is known for cabernet sauvignon, shiraz, mourvédre and other varietals. But any hunter visiting the property will also notice another bounty: Columbia black-tailed deer.

Columbia blacktails are cousins to the larger mule deer. They range from Southern California up the coast through Oregon, Washington and almost to Alaska. They are smaller than mule deer and have more compact antlers. They’re adept at using cover to stay hidden from predators, and in the case of the vineyard, they run the rows of vines like it’s their own labyrinth. Hunting them here is a game of cat and mouse.

Deer are thick as thieves on this 500-acre vineyard. Thieves is definitely the right word: The ungulates devour the profits by eating grapes and vines all day.

On August 9, the opening day of the 2025 rifle season, vintner and hunting guide Ryan Newkirk and I went right to a high spot on the property and glassed. I was distracted by the beautiful Santa Lucia Mountains to the west. I could almost see the Pacific on the other side. Closer was the city of Paso Robles, along the Salinas River Valley.

Within an hour, we’d seen more than 100 deer. Most were nanny does with fawns. Sometimes we’d glass bucks in bachelor groups, and occasionally we’d see a single buck tugging at vines that hung over its head. There were thousands upon thousands of deer on this property. But we were on the lookout for the oldest buck we could find.

If you hunt here at Steinbeck Vineyards, get used to glassing the rows of grapes, moving on to a different part of the vineyards, and glassing more. Just know, there are no shortage of deer.

Blacktail antlers probably won’t wow a mule deer hunter or Midwestern whitetail hunter. An SCI Gold Medal Columbia blacktail needs to measure 130 inches as a typical. Compare that to nearly 180 for a Midwestern whitetail typical minimum, and you realize that a blacktail won’t take up much wall space in your trophy room. Still, blacktail racks are something special. As compared to blacktails up the coast in Oregon and Washington, the Central Cali deer don’t usually score as well and have fewer overall inches.

The No. 1 typical Columbia blacktail in the rifle category was taken in Washington. Thomas Gogan shot the beast in 1960, and it scored 184 3/8 inches.

These Central California chapparal bucks, however, are known for wider racks as compared to northern blacktails that live in dense temperate rainforests.

Craig Boddington, Features Editor of SAFARI Magazine, lives near Paso Robles. He can’t get enough of his local blacktails, so he visited us at the Steinbeck Vineyard often during our hunts and helped us glass a few times as well. Boddington, perhaps more so than anyone else, has hunted world-record game animals from Africa to New Zealand. Yet he has a deep affinity for these little deer.

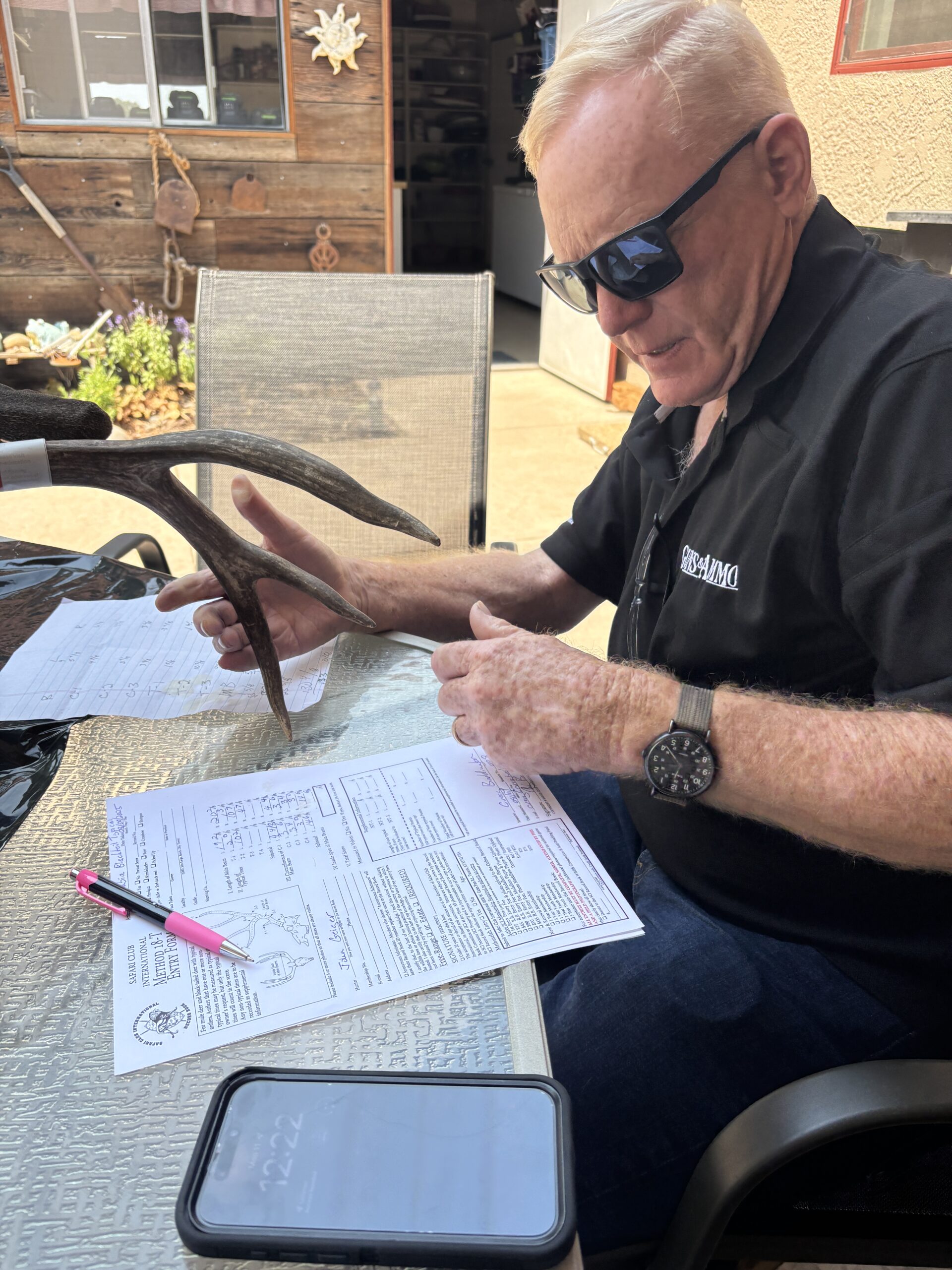

Craig Boddington, SCI Master Measurer No. 008, lives near the vineyard and dropped by to measure the buck. It scored 126 6/8, a Silver Medal Blacktail, according to the SCI Record Book.

“A big part is that they’re simply our deer,” said the local. “They are more homebodies than mule deer, tucking themselves into deep, poison-oak-choked canyons and rarely coming out into the open. On the Central Coast, the hot, dry summer seasons are tough. But it’s worth it.”

Glassing down onto the vineyard, it was easy to see up alleys and between vines growing on a trellis system. But you can only see one row at a time. It’s impossible to see anything a few rows over, a lot like looking down an early season corn row. Deer are exposed as they walk into your field of view, and they disappear as they slip through the lines of merlot, zinfandel or grenache.

After examining a few bucks, Newkirk spotted one he had never seen before.

“Oh, there’s a nice buck,” he said slowly.

This was a bigger-bodied deer compared to the others we’d seen so far. It had a dark coat, wide antlers and small eye guards. I have taken a fair number of mule deer from Canada to New Mexico, and I look for 4×4’s, also called a 4-point in the West.

When I saw it was a 3×3, I was not as impressed as Newkirk. I was prepared to hold out for a 4×4. After all, this was the first hour of a three-day hunt. An old adage ran through my head: Never pass a buck on your first day that you’d gladly take on the last day.

“What do you think?” said Newkirk.

“Let’s put a stalk on him and get a closer look,” I said.

We were able to get within about 200 yards. He was skylined between rows. The more I looked, the more I liked him. His bases were thick, and the spread was well beyond the ears. Suddenly, does emerged from the vines and surrounded the buck. He turned his back to us and fed away down the row between the vines.

This could be my chance. We hustled down the same row and set up about 125 yards from the buck. Newkirk put up a pair of Africa-style sticks, and I slid my Mossberg Patriot into the V. I took another glance at the rack through the scope to confirm I wanted to take this buck. The spread gave me the answer: There was no question that this was a special deer.

He circled a bit, like a dog about to bed. I put the Leupold duplex crosshairs on his vitals and touched my finger lightly to the trigger. As soon as he cleared the two does, I would pull the trigger and send the 120-grain copper bullet into his vitals.

That’s when he dropped down among the girls for his afternoon nap.

He bedded right there, and there was no way I could thread the needle among four does.

“Follow me,” said Newkirk.

We ducked back out of the vines to the dirt road.

“Do you mind a little bit of a hike?” said Newkirk.

“Not at all,” I said.

We circumnavigated a section of vineyard and arrived on a different hill that commanded a view of the astoundingly beautiful Central California landscape. I could see the lodge where we stayed, the building that houses the wine press, Newkirk’s grandfather’s house near the oak at the top of Olma’s Hill. I could trace the path of the Camino Real, where Spanish missionaries traversed in the 1700s, carrying the Gospel and grapes that would define the area to this day. There’s a lot of history here.

The Steinbeck family grow dozens of varietals, that is, types of grapes, at their 500-acre vineyard on California’s Central Coast. This area is well south of the more famous Napa and Sonoma valleys near San Francisco.

The Steinbeck family — distant relatives of the California writer John Steinbeck — has been planting, growing and harvesting on this land for more than 100 years. Howie Steinbeck, the living patriarch, first planted grapes here in 1982. Family, friends, land and wine are all very important to his clan.

They have several traditions as well.

When a deer is killed, they note what grapes were in the section where it was taken. Then they grill the rich deer heart outdoors under a shelter in the middle of the property and toast the day with the corresponding wine. Another tradition is the nightly gathering at a giant outdoor oak table.

Paso Robles means pass or road of the oaks in English, so it’s appropriate that family, friends and fellow hunters gathered each night at a big oak table to toast the day.

The Steinbecks serve dinner and wine in abundance. Family and friends gravitate to it like a magnet. Maybe it’s the tri-tip steaks prepared outdoors on a Santa Maria grill, a local specialty. Perhaps it’s just the good wine that flows constantly. I suspect it’s mostly the community the farm creates. Locals and visitors share stories and experiences in turn about their travels, all encouraged by the good food and drink.

Contemplating tradition, community and California’s fascinating history was not helping me spot our 3×3 buck from on top of the hill. I snapped back to the task just as Newkirk said, “There he is.”

To get a closer shot, we crawled to the top of the hill. Prone was not an option due to high grass, but I could use my Harris-style bipod to sit for a stable shot. To anchor the stock, I held Newkirk’s shooting sticks in my left hand and rested the foot of the stock on my left forearm. It was a solid rest.

The 3×3 was only 145 yards away, unaware. I’d only need him to lift his head for a center-chest shot. He looked up. I breathed out. At the bottom of my respiratory pause, I put pressure on the trigger until it yielded.

Prone was not an option due to high grass, so Geiger used a Harris-style bipod to sit for a stable shot. He held the guide’s shooting sticks in his left hand and rested the foot of the stock on left forearm for a solid anchoring.

The deer stumbled and fell. As I walked up to him, the width of the antlers, later measured at a 21- inch span inside the main beams, astounded me. I had always thought of blacktails as having compact antlers. Not this Central California specimen! This was truly a wide chaparral Columbia blacktail.

In fact, when Boddington, who is a Master Measurer, put tape to the anglers later that evening, the score came out to 126 6/8 inches, well into the SCI Silver Medal class and just a few inches short of a Gold Medal blacktail.

We showed it to Grandpa Howie that evening at the table. He ran his weathered hands along the tines. “Oh, there’s a nice buck,” he said slowly.

Howie talked about other nice bucks from the property in the past. He also talked about family and tradition. The cabernet paired perfectly with the deer steaks. A cool wind descended from the Santa Lucia Range. Glasses clinked. Bottles uncorked.

I asked the group of Californians at the table how they possibly moderate the intake of fine wine with such abundance.

Michelle Steinbeck, Newkirk’s mother, spoke for the group.

“Well, we’re still working on that,” she said. “Cheers.”

GEAR TO GO

Smaller Caliber, Bipods Made the Shot

Central California blacktail generally weigh no more than 160 pounds, so you don’t necessarily need a magnum caliber to dispatch these bucks.

I chose 6.5 Creedmoor due to its light recoil, long-distance accuracy and tremendous number of good bullet options.

In California, hunters cannot use traditional bullets but must use non-lead projectiles. (Leave your suppressor at home as well; they are illegal to possess in California.)

Remington’s Premier CuT, Copper Tipped cartridges did the job nicely. The 120-grain bullets gave me consistent minute- of-angle groups and acceptable standard deviation when chronographed with a Garmin Xero C-1 Pro at the range. The muzzle velocity was advertised at 2,932 fps, and I got mid-2,800s with my 24-inch-long Mossberg Patriot barrel.

The Mossberg Patriot Walnut is a very capable and good-looking rifle. Chambered in 6.5 Creedmoor with copper bullets, and a Leupold Vx-3 scope, it was effective at the range and in the field. The rifle’s MSRP is $739.

The Patriot model has continued to impress me despite my original skepticism when it first came out in 2015. Back then, I could not get good groups from a first-gen production rifle. Since then, the Patriot’s accuracy has seemed to greatly improve.

I asked Richard Kirk of Mossberg what they have been doing differently with the barrels since the first generation.

“Not a thing,” he said. The barrels are drilled, reamed and then button- rifled as they’ve always been.

Someone mentioned that maybe Mossberg was rushing the Patriot out the door in the heady days of 2015. But now, as the industry has slowed down some, they’re able to take time to make sure they are all shooting lights out before they leave the factory at Eagle Pass, Texas.

Another aspect of the Patriot that pleased me was the stock and was expecting to open the box to see bland and uniform wood. While it’s not going to wow any serious collector, the stock had some figure and character. Kirk of Mossberg also said the walnut is the same wood as they’ve used for this rifle. But they no longer use wood filler on the stock. That’s good because then you can see every bit of grain. This model costs $739 at mossberg.com.

Howie Steinbeck was born and raised on this patch of land near Paso Robles, California. His grandson, Ryan Newkirk, now takes care of the property.

CONSERVATION QUESTIONS

Management Tools Are Limited Here

The Steinbeck family doesn’t advertise their deer hunting opportunities. They are a vineyard first and host hunts here and there through the early bow and rifle season, which starts in July. But Ryan Newkirk ([email protected]) said he is happy to guide hunters there.

These blacktail eat a tremendous amount of the profits each year. Not only do they chow down on the precious grapes, but they also denude the vines of leaves, and the grapes don’t fully mature without the shade, he said. While taking some bucks might help reduce the population, every land manager knows you have to reduce the number of does to control the herd population.

In San Luis Obispo County, part of Zone A, taking does is illegal on the general deer tag. Depredation tags are few and far between. Newkirk requested a depredation permit from the California Department of Fish and Wildlife to manage his growing herd. A state biologist arrived at the property and did a population survey. A few weeks later, Newkirk received the permit. He could take only two does.

That anemic solution would have no effect on a population in the thousands and growing. It was disheartening to say the least, said Newkirk.

The big picture is that these deer will continue to increase in number and decrease farm profits. In 2024, deer accounted for a 20% drop in product harvest, according to the farm’s record.

With hunting of does off the table to control the herds, other vintners in the area have turned to high fences to keep deer out of their properties. But there are downsides to that solution.

“I don’t feel like I am being a good neighbor or a good game manager if I build more fences,” said Newkirk.

He said he would be simply pushing deer off his property and onto local roads.

“That’s dangerous considering the large number of deer we have here,” he said. “It doesn’t seem right.”

Fences and taking the occasional buck are the only tools the Steinbecks have to protect their business from these voracious deer.

Thankfully, hunting in the vineyards, playing cat-and-mouse with blacktail bucks and bringing home fine backstrap steaks to accompany delightful wines is not such a bad consolation.

“We make the best of it,” said Newkirk. —JG

Columbia black-tailed deer have a compact triangular head as compared to mule deer and whitetail.