Unless you’ve been living in a cave you must be aware that the 6.5mm Creedmoor is the hottest centerfire cartridge on the planet! Everybody’s talking about it and everybody wants one. Gunmakers are chambering it to more platforms, and selection of loads is increasing rapidly.

The 6.5mm Creedmoor is a neat little cartridge, but I find its sudden rise to popularity a real phenomenon. You see, it’s not new, — although its celebrity certainly is. Designed primarily as a long-range target cartridge, the 6.5 Creedmoor was introduced by Hornady in 2007. At first it rolled along without much fanfare. Then, after nearly a decade, it took off like a rocket. Typically, a new cartridge either quickly gains acceptance, or it doesn’t. If it doesn’t take off fairly quickly, then in my experience it rarely ever will. The Creedmoor broke that mold.

The Creedmoor is a good and very accurate cartridge. Its ballistics are credible but not flashy — 140-grain bullet at about 2,700 fps. Light in recoil, it’s fun to shoot. It takes advantage of the 6.5mm (.264-inch) bullet diameter’s long-for-caliber bullets, which tend to retain velocity well. The Creedmoor’s short case is well-suited to long, aerodynamic bullets, which has endeared it to long-range shooters. Although muzzle velocity is modest, such bullets remain supersonic until way out there (beyond 1,200 yards). This is critical in long-range shooting because the turbulence of crossing the sound barrier is avoided. And the farther you can shoot with the least recoil is to the good.

However, the current popularity of the 6.5mm Creedmoor goes far beyond the relatively small cadre of serious long-range shooters. It’s being snapped up by hunters and target shooters, both casual and avid. There is one more unusual thing about the Creedmoor’s rise: The fact that it’s a 6.5! 6.5mm, caliber .264, has been a standard and popular bullet diameter in Europe since the 1890s, but there have been many decades when you couldn’t give away a 6.5mm here in the United States and over the years most of the (few) domestic 6.5mm cartridges have failed.

Right now, the 6.5mm is having a great day in the sun, and it isn’t just the 6.5mm Creedmoor. The shorter 6.5mm Grendel, sized to fit the AR-15 frame, is also red-hot. It’s a bit too soon to make any predictions about the new 6.5mm PRC (Precision Rifle Cartridge), also from Hornady, but for sure there’s a lot of buzz. We also have two new super-fast 6.5mm cartridges, the 26 Nosler, and the 6.5-.300 Weatherby Magnum.

So perhaps we’ve turned a corner and the 6.5mm will find lasting popularity in the U.S., but this is not the first time the 6.5mm has caught our eye!

GOING BACK

Smokeless powder began to replace blackpowder in 1886. For the next decade, the world’s arms makers scrambled to develop smokeless powder cartridges, incorporating the parallel development of the jacketed bullet. Between 1891 and 1900, seven 6.5mm cartridges were adopted by various militaries around the world. Almost all used long, heavy-for-caliber bullets from 150 to 160 grains, mostly at typical “early smokeless” velocities between 2,300 and 2,400 fps. Some have nearly vanished while others are familiar from the surplus military markets: 6.5×50 Japanese, 6.5×52 Carcano. Military cartridges, however, do have a history of becoming popular sporting cartridges.

The first to have significant impact in the sporting world was the rimmed 6.5x53R Mannlicher. Adopted by the Netherlands and Romania, it quickly became popular among British sportsmen. Following the British convention of naming cartridges by the smaller land (rather than groove) diameter, they quickly called it the “.256.” It’s rare today, but the two with the more lasting impact are the 6.5×54 Mannlicher-Schoenauer, adopted by Greece; and the 6.5×55 Swedish Mauser.

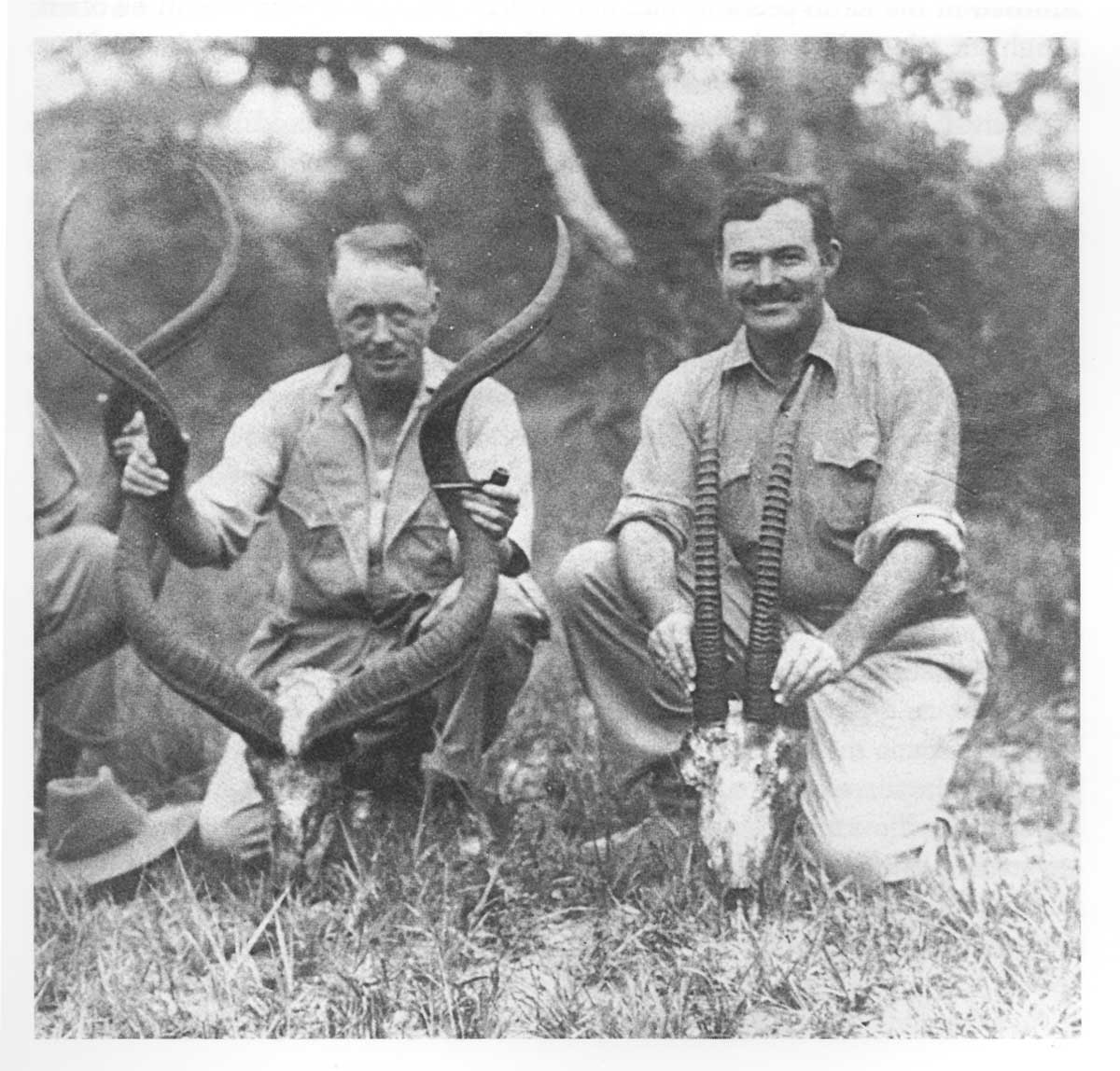

The 6.5×54 is a rimless cartridge that was quickly dubbed the “new .256” to distinguish it from the 6.5x53R. Both the 6.5×54 and 6.5×55 attained significant followings in the United States. Ernest Hemingway had a 6.5×54 Mannlicher on his “Green Hills” safari in 1934. It is still seen today; our esteemed Editor, Steve Comus, admitted that he has three and still hunts with them. The 6.5×55 has been more popular over here; it is still loaded by U.S. ammunition companies and occasionally chambered in domestic rifles (Kimber for example). In the early years, however, the only American 6.5mm was the .256 Newton. Based on the .30-’06 case necked down, it was designed by Charles Newton in 1913, and was loaded by Western until 1938.

Charles Newton’s last manufacturing effort failed in the 1920s. There would not be another American 6.5mm cartridge for more than 30 years. It was, of course, the .264 Winchester Magnum, introduced in the Winchester Model 70 “Westerner” in 1958. Fast and flat-shooting, at first the .264 Win. Mag. looked like a superstar; the gunwriters gushed, and initial sales were excellent. In 1962, however, Remington’s 7mm Remington Magnum blew the .264 off the market. The “Big Seven” is more versatile, but the .264 had issues that the public soon discovered. There was some blue sky in the initial published velocities; it was supposed to push a 140-grain bullet at 3,200 fps, but it never quite got there. Later the claim was reduced to 3,030 fps where it remains today. It needed the 26-inch barrel the Westerner was introduced in, and throat erosion was rapid.

The .264 Win. MAG. is still loaded but rarely chambered. Oddly, this handwriting was already on the wall in 1966 when Remington introduced its 6.5mm Remington Magnum. Based on the 7mm Remington Magnum case shortened and necked down, the 6.5mm Remington Magnum fits into short bolt actions and comes close to the .270 Winchester in performance. It never went anywhere, and it was about that time when gunwriters (if not manufacturers) started talking about “the curse of the 6.5mm” in America.

The .260 Remington may be the final evil done by this curse. Introduced by Remington in 1997, it is simply the .308 Winchester necked down to 6.5mm. Jim Carmichel, then of Outdoor Life, described it as the “most accurate cartridge based on the .308 case.” Honestly, I haven’t seen that, but here’s the odd thing: The .260 Remington is ballistically identical to the 6.5mm Creedmoor. Some 1,000-yard shooters prefer it, but despite being so similar—and-predating the Creedmoor by a decade—it has not been nearly as popular as the Creedmoor. The Creedmoor has created not just new interest, but more American interest than ever before in the 6. 5mm. It seems to me we now have three “classes” 6.5mm cartridges: Fast, faster and fastest.

FAST

Some of the older military 6.5mms were pretty slow. Not too long ago I chronographed some European 6.5×54 ammo. With the heavy 156-grain bullet, it was clear down to 2,000 fps — far below specifications. 6.5×50 Japanese and 6.5×52 Carcano ammo is still available but is also loaded very slow because of concerns over weak actions. Otherwise there aren’t any really “slow” modern 6.5mm cartridges. Slowest is the 6.5mm Grendel, designed by Alexander Arms; again, it’s sized for the AR-15 action, so cartridge length is limited. Standard is a 123-grain bullet at 2,610 fps. If I was looking for an AR-15 “upper” with significantly better performance than the .223, especially for hunting, I’d go to the Grendel.

The common “fast” 6.5mms are the Creedmoor, .260 Remington and 6.5×55. They are actually ballistic equals. The 6.5×55 suffers from concerns over older (pre-1898 Mauser) actions, so American factory loads are mild. However, the 6.5×55 has greater case capacity than the Creedmoor or .260, so with handloading can exceed either. Against that, the 6.5×55 has a longer case and cannot be housed in a short action, while the 6.5 Creedmoor and .260 Remington are short-action cartridges. So, take your pick but figure all three will push a 140-grain bullet at about 2,700 fps.

These are marvelous cartridges for deer-sized game, and certainly adequate for elk at medium ranges. Using heavier bullets, the 6.5×55 remains a favorite for moose in Sweden and Finland! All three are excellent long-range target cartridges with mild recoil and great performance, but in my view none of the three should be considered long-range hunting cartridges, especially for game larger than deer. The energy just isn’t there. But there are faster 6.5mms that deliver more energy downrange!

FASTER

I suppose 300 fps faster doesn’t sound like a huge improvement, but things change a lot when you get the aerodynamic 6.5mm bullet to 3,000 fps. There are three common cartridges in this class: 6.5-.284 Norma, .264 Winchester Magnum and the new 6.5mm PRC. A fourth is the European 6.5×68. Though almost unheard of in the U.S., the 6.5×68 is an unbelted cartridge popular among European hunters, especially for chamois. All of these are ballistic equals. The 6.5-.284 Norma, based on the .284 Winchester case necked down, was standardized by Norma in 1999. It can be housed in a short action, while the rest require standard (.30-’06-length) actions. The 6.5-.284 was intended as a long-range target cartridge, likewise the brand-new 6.5 PRC.

However, all of these are excellent hunting cartridges; push an aerodynamic 140-grain bullet at 3,000 fps and you can project about 1,900 foot-pounds to 300 yards. In my mind this makes this group sound elk cartridges to beyond 300 yards; and for the deer/sheep/goat class you can go farther. I have the most experience with the .264; I got my first .264 in 1965 and I thought it was magic. It wasn’t, but I still have a soft spot for the .264, and I’ve used it recently in Africa and Asia as well as for North American hunting.

FASTEST

For decades, the .264 Winchester Magnum and 6.5×58 were the fastest 6.5mm cartridges. In 2014, Nosler changed the game with its 26 Nosler, a 6.5mm based on the big .404 Jeffery (or 7mm Remington Ultra Mag) case shortened a bit and necked down. It can be housed in a .30-’06-length action, and it propels a 140-grain bullet at nearly 3,300 fps. Two years later, Weatherby changed the game again with its 6.5-300 Weatherby Magnum. Based on the full-length .300 Weatherby case necked down, the 6.5-300 requires a magnum-length action. It’s about 100 fps faster than the Nosler so, with no argument whatsoever, it is the world’s fastest 6.5mm cartridge.

The difference between the two is not extreme. I have used them both with excellent accuracy. Obviously, you are projecting more energy farther downrange. Both are superb long-range cartridges for deer-sized and mountain game, and clearly both are fully adequate for elk-sized game at significant range, but whether I would consider any 6.5mm an ideal choice at the extreme ranges some folks are shooting at today is another story. Ultimately, you are still dealing with relatively light bullets of moderate diameter. So even the fastest cartridges don’t turn the 6.5mm into a long-range brontosaurus buster. But, man, do they shoot flat and, on game, you will notice that the bullet gets there fast!

The entire 6.5mm landscape has changed — more cartridges, more capability, better bullets and much more availability. At this moment, in 2018, the 6.5mm has come alive. This time I think it’s here to stay, but only time will tell.–Craig Boddington