John Charles Anderson wrote three books about hunting in Africa, all of them now considered classics. His final book, The Lion and the Elephant is one of the hardest to locate in original condition. To this day, it is considered one of the best on hunting both of those game animals. The story that follows is recalled by one of Andersson’s friends about lion hunting with the locals, or colonists, as they were then called.

We were on Thompson’s farm at Barlon’s River, in the neighborhood of which numerous heads of large game, and consequently beasts of prey, are abundant. One night a lion, who had previously purloined a few sheep out of the kraal, came down and killed my riding horse about a hundred yards from the door of my cabin. Knowing that when a lion does not carry off his prey, he usually conceals himself in the vicinity, and moreover is very apt to be dangerously prowling about the place in search of more game, thus I resolved to have him destroyed or dislodged without delay. I therefore sent a messenger around to the location, to invite all who were willing to assist in the foray, to present themselves to the place of rendezvous as soon as possible.

In an hour, every man of the party, with the exception of two pluckless fellows who were kept at home by the women, appeared ready, mounted and armed. We were also reinforced by about a dozen of the bastard Hottentots who resided at that time in our territory as tenants or herdsmen. They are an active and enterprising, though rather unsteady, race of men.

The first job was to track the lion to his covert. This was accomplished by a few of the Hottentots on foot, commencing from the spot where the horse was killed. They followed the spoor through grass and gravel, and brushwood, with astonishing care and dexterity, where an inexperienced eye could discern neither footprint nor mark of any kind, until at length we tracked him into a large “bosch” or straggling thicket of brushwood and evergreens about a mile distant.

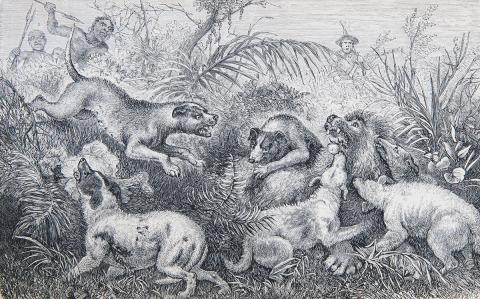

The next object was to drive him out of this retreat in order to attack him in a close phalanx with more safety and effect. The approved mode, in such cases, is to torment him with dogs until he abandons his covert, and stands at bay in the open plain. The whole band of hunters then move together and fire when appropriate. If however the lion manages to charge, the hunters must stand close together and turn their horses’ rear outward. Some men hold the horses while others hold their rifles. If they only wound the lion, the business becomes rather serious, especially if the men are not of above average coolness and experience. Generally however the frontier Boers are excellent marksmen, as well as cool and deliberate so they seldom fail when they get within a fair distance.

But in the incident described, things did not go so scientifically. The Hottentots, after recounting to us all the above and other sage laws of lion hunting were the first to depart from them. Finding that with the few indifferent hounds, we had made little impression upon the enemy, they divided themselves into two or three parties and rode round the jungle, firing into the spot where the dogs were barking, but without effect. At length, after some hours spent beating about the bush, the Scottish blood of some of the men started to get impatient, and some of the men announced their intention to break in and get the lion in his den, provided that three of the Hottentots who were superior marksmen, would support them and follow up their fire, should the lion venture into battle. Accordingly, and in spite of warnings from some of the more prudent men, they went in to within 15 to 20 paces of the spot where the lion lay concealed. He was crouched among the roots of some large evergreens but with a small spot of open space on one side of it. On approaching, the men fancied that they saw the lion lying down and glaring at them from under the foliage.

Admonishing the Hottentots to remain firm and calm should they miss, the men fired as one and struck (as they learned afterward), not the lion but a large great block of red stone, beyond which the lion was actually lying down. Whether or not the shot grazed the lion is not known, but with no other warning than a furious growl he burst forth and bolted from the bush. The cowardly Hottentots, in lieu of standing firm to fire, instantly turned and ran helter-skelter, leaving the lion to do what he wanted to with the defenseless Boers, who, with their empty guns, were tumbling over each other in their hurry to escape the clutch of the rampant savage. In a twinkling he was upon them and with one stroke of his paw dashed the nearest to the ground. The scene was terrific!

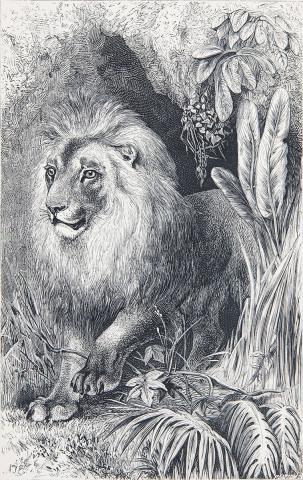

There stood the lion, with his foot upon the prostrate foe, looking round in conscious pride upon the bands of his assailants with a demeanor the most noble and imposing that can be conceived. It was the most magnificent sight I ever witnessed. The danger of our friends, however, rendered it at the moment too terrible to enjoy either the grand or the ludicrous part of the picture. We expected at any moment to see one or more of them torn into pieces. Worse, though the rest of the party was standing within 50 paces with their guns cocked and leveled, we could not fire to assist them. One man was lying under the lion’s feet and the other was scrambling towards us at such a pace and angle that he would have intercepted our aim.

All this happened far more rapidly than I have described it. But, luckily, the lion, after steadily surveying us for a few seconds, seemed willing to be rid of us on fair terms. With a fortunate forbearance, he turned calmly away, and driving the snarling dogs like rats from his heels, bounded over the adjoining thicket like a cat over a footstool, as readily as if they had been tufts of grass. After abandoning the jungle, the lion retreated towards the mountains.

After ascertaining the state of our rescued comrade, who fortunately had sustained no other injury than a light scratch on the back and a severe bruise on the ribs, from the force with which the lion had dashed him to the ground, we renewed the chase with the Hottentots and hounds in full cry. In a short time we again came up with the lion and found him standing at bay under an old mimosa tree, by the side of a mountain stream which we called Douglas Water. The dogs were barking furiously but were afraid to approach for the lion was beginning to growl fiercely and brandish his tail in a manner that indicated he was meditating mischief. Some of the Hottentots, by taking a course between the lion and the mountain, crossed a stream and stationed themselves on the top of a precipice overhanging the spot where he stood at bay, while others of them took up a position on the other side of the glen. Thus the poor lion was placed between two lines of fire. This situation both occupied his attention and prevented his retreat. Finally a couple of us shot, and the lion, wounded and in his glory, fell to the ground.

The Hottentots, who are thought of as lion hunters by the Boers are so cautious as to remain devoid of either danger or excitement. They never dream of firing until a distant, safe, and convenient position has been found. Then they all sit down comfortably together and shoot. Though colonists and their neighbors usually hunt the lion in a group, at other times, a single individual, usually a foreign trophy hunter who visited Africa for the sake of sport, takes part in the chase and wants to be the only or first person to fire. On these occasions the hunter usually waits to fire until the lion crouches or stands at bay to the dogs. If mounted on a horse, the hunter must be careful not to approach too closely, for if he misses, and does not get a good start on the horse, the outcome can be doubtful. Indeed, if one is too close to a lion when it starts to charge, a hunter can be placed in a dangerous or even critical situation.

The lioness is a much less imposing looking animal than the lion, being not only one third smaller but also devoid of a mane. When roused, however, either by rage or a hunter, she has an even more ferocious aspect than her stately mate, whose countenance is often partially hidden by his stately mane. It is said that, as a rule, the lioness is more fierce and active than the lion and that those who have never had any offspring are more dangerous than those that have had families. Furthermore, it was generally thought that when a lion and lioness are in company, the lioness is always the first to roar.

For example, William Cotton Oswell, the noted hunter and explorer, was one day pursuing a lioness who after a while took refuge in a dense thicket. The dogs came close and barked loudly, and the lioness growled. But the bushes prevented Oswell from obtaining sight of her. However, he continued on some little distance beyond the area where she was hidden. He was suddenly attracted by a noise coming from behind. He turned around just in time to see the cat coming towards him. The cat being on Oswell’s right side rendered him unable to fire. Even had it been otherwise, he would hardly have had time, for in a second or two he felt his horse stagger under him. On turning round again, he saw the lioness perched on the hind quarters of the poor animal. Happily for Oswell, the horse, at the instant of the attack, swerved to one side. The horse then came into contact with a thick thorn bush and both the rider and the lioness were swept off the horses’ back to the ground. The concussion stunned Oswell and he had no recollection of what happened afterwards. As the lioness did not molest him in any way, it was assumed that with the fall and subsequent onslaught on the dogs, the lioness was also perhaps confused and took herself to distant cover.

Thus, in spite of all that has been said and written about the lion’s bravery compared to other dangerous game, I venture to say that people who are well acquainted with the lion in its native wilds, and who have confronted one in battle, whether by night or day, will not fail to pronounce the lion among the bravest of beasts, as well as having undaunted and almost unconquerable spirit.–Selected and edited by Ellen Enzler-Herring of Trophy Room Books